- I can't stand English tea! Because when the Nazis left we had nothing to eat or drink for two weeks or so. When the English arrived the first thing they gave us was tea, and we were all sick and since this time I cannot drink tea.

I raised my eyebrows and grinned at her. In my mind I pictured the Brits, faced with the horror, running round panicking.

- Jesus Christ, what the hell should we do?

- I don't know mate, put the kettle on, and then we'll sort it all out.

I shrugged.

- Well, erm ...

I giggled a little.

- Coffee then?

What Aunty Ruth was talking about was being in the Camps. Liberated by the British, who forty-odd years later finds herself being breakfasted by another Brit from darkest Birmingham, in an old Sudeten-Deutsche Lodge in the mountains on the border of Poland and Czech.

It had taken me a while to persuade Aunty Ruth to come visit us. She was never one to rough it. Ruth wanted the finer things in life, a little luxury, and who could blame her?

When I had first visited her at her artist husband's flat we had partaken of coffee in the drawing room surrounded by art.

Served cakes were on blue patterned china, I grabbed at a coconut flecked jam sponge. The conversation stopped and all eyes turned.

I stopped and held the cake at my open gob.

My eyes moved left and right.

- What, what?

- We do have cake forks you know!

Of course she did.

So, anyway it had taken me ages to convince her that our little hideaway was of the highest standard, and it was.

Antique and rustic furniture mingled with communist relics and First Republic gadgets.

We picked her up from the train station, and drove slowly through the blinding snow storm. The smell and glow of oak welcomed her in.

She handed over two small packages. Two decorated paper bags. Inside two treasures unwrapped.

-If you don't like them you can sell them.

We looked inside; I had a silver cigarette case, her husband's. My wife had a miniature powder-puff case, silver.

- No no, we love them, thank you.

* * *

Ruth's husband's art was all over our place, this made her happy, and she looked at the picture of the farmhouse in Crete where they had managed to get to one year, and smiled a little.

He had given some of it to us for a wedding present, this was when he was alive, well barely, as he was quite ill, and used a bag and a cane, as they had operated on the wrong leg.

I had admired the man and his art, so was very happy to receive the case. Unfortunate then that I had switched to electronic cigarettes six months before. But still, it looked nice on the bookcase.

The powder-puff case was another story.

Ruth's great Uncle Oldrich had been in the Great War; reluctantly fighting for the Empire, against the British.

He was captured by the British and sent to a camp in Scotland. The prisoners were treated well, they never tried to escape, why would they? However, the weather did not agree with a lot of the middle-Europeans, and Ruth's great uncle became very ill with pneumonia.

He was cared for very well, he said. The doctors were very kind. He had a fondness for your British tea too, which is funny.

The uncle returned to Moravia where he spent months and months in a special Spa. He bathed in and drank smelly cloudy sulphur waters to help. Ruth visited as often as she could, she sang songs and read books to him, for comfort.

Now, during all this time he had done the lottery. Every week without fail he would place a little money on his lucky numbers. Even when he was away his wife had firm instructions to place money on the numbers.

Eventually his illness worsened and they had to amputate his legs. The following week, he won the lottery.

He won!

He won a motorbike.

When he was well enough he was told this by his wife, he laughed. He laughed for such a long time he brought on a coughing fit and was very ill again for a few days after. Eventually he got better and instructed his wife to sell the damn motorbike. When well enough to return home, his wife pushed his wheelchair around the plush department store in Brno as he picked out little presents for the people he loved. One of those presents was for his favourite little niece, and for her he picked out a very small powder-puff case. Just the right size for a little lady.

* * *

We were separated at school.

Suddenly the teachers got nasty.

Urging the other kids, our friends, to mock us.

Why? I didn't understand it.

'Why Mama? What did we do wrong?'

There were few answers.

Some people came to our house. They seemed like Police, but new Police.

They took away my things. And all the bright things in the house. Anything pretty.

I hid the little powder-puff case in my special hiding place.

Uncle Oldrich had told me to take special care of it.

The nastiness and stupid things continued.

I couldn't understand it.

Nobody seemed to understand it.

We were made to sew the Star of David on our clothes.

Our neighbour's shops were burnt or left windowless after a night of rain and a morning of sun that left the streets sparkling and smoking.

An old lady spat in my father's face as he held my hand on the way home from school for the last time.

I held his hand so tight.

If I held his hand I thought everything would be all right.

'Why can't I go to school Dada?'

'Don't worry Ruth, one day you will go back.'

'But Dada, I am a good student, why can't I go to school, I don't understand?'

'Some people don't want us there Ruth, bad people ... but they won't always be there. We have seen this before. Things will go back to normal, you will see.'

'Do you promise?'

'I promise.'

I could see in his eyes that he hadn't really promised. Not like when he promised to take me to the boating lake, or to buy me the flowery dress in Mr Benes's window.

It wasn't a promise like the one when he told me about the huge slices of cake and ice cream he would buy me for my birthday in the Tivoli Kavarna.

Now, his eyes showed fear and I knew he couldn't keep his promise.

Mr. Polosky's shop was all burned out, and I didn't know where he had gone. Many people, our neighbours, had just gone. One minute they were there, then they disappeared.

My best friend, Eva was gone, she didn't even say goodbye.

No one would say where people had gone.

My Mother came home and sat at the table. She burst into tears, her head in her hands.

My Father stood over her, stroking her long black hair.

She had been sent home from the hospital, where she helped the new babies.

Others in our street and around were sent home. People stopped working.

We had to queue for food, awful food.

My Father was still able to help his patients. But was given no medicine to help them.

He pleaded at the community centre to the more important men in our community. They did nothing to help him.

The queues got longer.

The new uniformed people started to order us around, not just the new Police force, but people who had been our friends, our neighbours. They began to shout at us.

Some came and argued with my father in the street, by the lines of people waiting to see him.

They pushed people away, and sometimes hit them. And screamed in their faces.

I wanted it all to end. At night I closed my eyes and tried to wish it all away.

It felt like when I had a bad dream and I couldn't reach something or couldn't run fast enough, and tried to wake myself up, because I knew I was dreaming, but couldn't wake up.

It felt like this.

* * *

The street shook from heavy trucks. I looked out of the window. They were all over the square.

Orders were being shouted out in a nasty sounding German. Red-checked men in helmets clattered out of the trucks, busy as ants. They all looked very disorganised, until they were ordered to halt. And then like mechanical ants they were all in order.

The soldiers entered all the buildings, shouting and shouting, pushing and pushing, making people leave their apartments. Doors were booted in. Office workers were hurried into the street. People grabbed coats and boots.

We went down quickly, we didn't want the ants to come inside our home. We were pushed by guns under the Baroque arches of the square. Those of us who had coats and the shirtless office workers.

The mayor of the town Mr Sheller, was busy, his red face was redder than usual, and his usual lovingly greased moustache was a bit shabby! He hurried and complained about being pushed. And he straightened his top hat and pushed his bursting waistcoat out. And wanted to know what the meaning of this was.

I remember these words.

'What is the meaning of this, I am no Jew, why are we being pushed around?'

The other office workers mumbled complaints also, mainly to the new police, as the soldiers stood a little way off, not talking, or moving, just watching. The police ordered silence.

We were separated; girls with mothers,

I cried as they dragged, shoved and beat men and boys onto waiting Lorries. People screamed, people begged, people pleaded.

I held out my arms desperately, trying to reach someone.

I ran after the trucks as they left.

That was the last time I saw my Dada and my brothers.

I knew we were going to be taken away, so I managed to run into our flat and take the powder-puff case from under the floor boards. I hid it in my knickers thinking that no one would look there.

* * *

- So what happened?

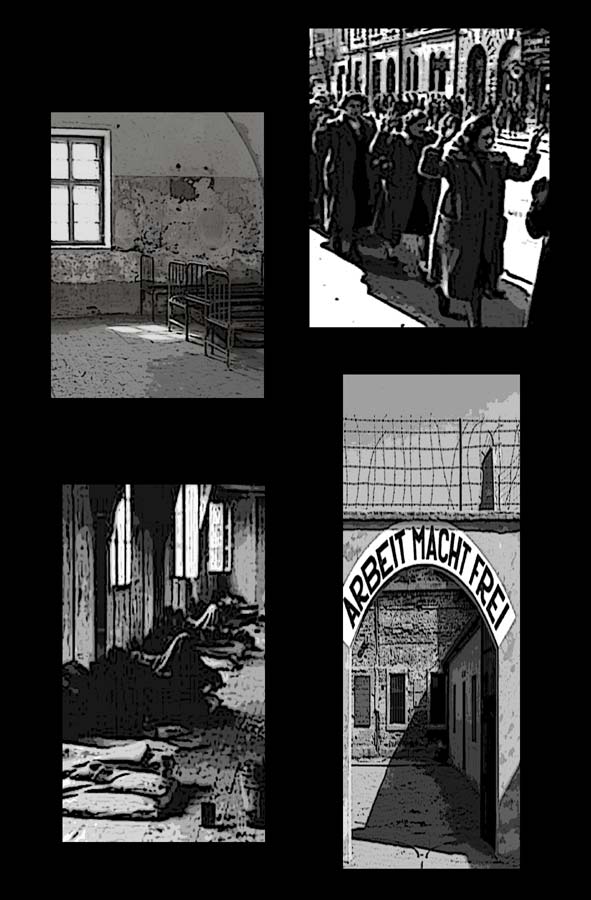

- Well, my mother and I were taken by train to Terazin camp, you know of this, yes?

- Sure.

- The Journey was terrible. One bucket for toilet and one of a foul smelling water. We slept all bodies entwined, out of necessity and for the need of warmth.

Things were not so bad there, I mean not so bad as what I experienced later.

We were over-crowded, but there was some food and some normal life. I even went to school, not a normal school, just some classes given by teachers.

But many people died. I was afraid and cried all the time, my mother covered my eyes, but couldn't stop me seeing.

I became a woman. My childhood taken from me.

There were tradesmen, carpenters and toolmakers, cobblers and tailors. My mother found a cobbler who put a special heel on my boot, somewhere I could hide the case.

In the dormitories we slept two, three to a bunk with one sheet.

After some weeks we were put onto train trucks again. We travelled for weeks.

When we arrived at the station on our final stop, we were told that this was an educational work camp.

Some thousand or so people were separated and as we stood shivering. We heard volley after volley of shots in the distance.

We were a few hundred left now, all women. Other women were marched to other such camps.

Our huts were basic, with a stove. We had little fuel but we scraped enough together to have some heat. We were allowed to mingle freely in the parade ground.

We listened to stories and rumours of all sorts; hope, no hope, savagery, kindness, slaughter, rehabilitation. Rescue.

We were made to work in the forests and the quarry. The work was exhausting. We were given soup and black bread.

Our guards were Estonians or Russians. Some were kind, some not. Some gave us extra food and smiles.

My mother was taken ill with typhoid as were many, they were not cared for but taken away, I didn't know where.

One guard was taken by my friend Tasha, who had comforted me after my mother left. We snuggled in my bunk and tried to give some of the love back that had been taken away from our lives; we slept, in embrace, holding a comfort.

This guard Otto smiled at first, tipped his hat, then talked more and more to Tasha when he could, and gave her chocolate. Chocolate! It was as if a fairy Prince has given her a palace of gold. We shared the chocolate, at night, under blankets.

Otto and Tasha took great risks in trying to meet and just talk.

One day Otto gave Tasha a small red lip-stick ... There were no mirrors in the camp.

What does someone need with a lip-stick in hell?

None of us had even looked at ourselves for a long time, only in the reflection of water.

At night, when no one was looking, I unlocked my shoe hiding place and gave her the powder-puff case. She cried when she looked at herself; blotched red face, matted hair, scratches, scars, and oldness.

We the girls scrubbed her face and body, and with much pain tried to untangle her hair.

The day was a holiday for the guards, and a day of rest for us. The atmosphere was relaxed. We snuck away and got out the case again. And with no-one watching she applied the red lipstick and then walked to the fence, to Otto.

He looked at her for a short time ... we were huddled together watching from a short distance.

He looked at her and tears rolled down his checks. He didn't speak, he took off his hat and with a sweep of his hand before him he bowed. Towards a woman.

* * *

- Jesus, what a story!

-And what happened?

- Otto and Sophie planned an escape ... under cover of darkness. We all collected a little food and clothes, the best as we could manage. She left dressed as an Estonian day worker. And we heard nothing for days. Then we heard rumours; they had escaped to Scandinavia, they had been shot.

We all clung to the story of our Romeo and Juliet. That was our hope, our fantasies under the rough blankets at night.

We heard nothing for a few weeks and we had hope.

But one day we all stopped work and walked to the wire, and watched in shock and disappointment as they were marched back through the camp.

They untied their hands and made them stand straight in front of a firing squad against a fence with the expanse of the wilderness behind them. As they tried to reach for each other's hands a volley of shots ripped into their bodies. As the echoes faded the brownness of their bodies let out a glow of steam as the red stained the white of the snow and seeped into the mud, their fingers were touching.

* * *

- And your mother?

- I never knew what happened to her at the time.

We were moved on very quickly, into wagons again, there were no sick or old this time. We travelled for days, to the final camps.

- Oh my god, so sorry.

- Don't be sorry, it was not your fault ...

- Yes but ...

- There is nothing one can say of these things ... I cried for sure, but I had to live ... to live for us both.

But one thing I must tell you about the Powder puff. Before we left another friendly guard called Libor warned us not to take anything we had hidden, these camps would be in Germany and Poland and much worse. I sat all night thinking if to trust this man. I did ... I gave him my powder puff case and he promised to hide it for me, and maybe one day if I could, I would go and he would return it to me.

- And you went back?

- You are a very impatient man ... We were taken to the extermination camps. And I was one of the few who survived. I was lucky.

You have read all about these camps I take it, so I won't bore you with the details.

- Bore me ...

After the liberation, after months of being logged, made well, documented, pushed here, taken there, injected here ... I eventually made it back to Brno. I was placed in a care home, and they cared for me.

- And what about the case?

- There's another chapter to come, let's have more coffee and I'll tell it.

* * *

In the 1960s I applied to visit Estonia to visit the camp where my mother died. The red tape was terrible, the authorities didn't want the past racked up, so made it terribly difficult for me to get a travel permit.

I wrote to a professor of art in Estonia who knew of my husband and who had fought against the Nazis.

We corresponded and he pulled strings, wrote letters, called in favours; did everything he could to get me a travel pass. When it arrived, or I should say they as there were mountains of documents, I cried.

The Journey was long, I took it alone and at every official juncture my journey was hindered. I passed through scenery I seemed to remember, this time in a fairly comfortable little carriage. The people were very polite to me except the border guards, and at every frontier I was taken in for questioning, and to have all my papers checked over and over again.

I eventually made it to Tallinn and met the professor, who gave me shelter in his apartment, and made me most welcome. We journeyed to the place where the camp used to be. This was the saddest part for me, the most vivid memories came back into my mind. We visited the village close by. We were met by the Mayor, a courteous man, but again I was questioned by local party members, and had papers checked and checked. We were taken to a small graveyard near to the outside of the old camp that was now a pig farm. There was a little graveyard, with flowers, and little wooden crosses ... there was a plaque commemorating the women who had died there, and there was my mother's name. I knew she must have died, but one always lives with a faint hope if one has not been told the full truth. This was my mother's resting place. I thanked them all. They were happy to receive a relative of one of the people from the camps. Happy to know that I, a person, had survived, and was here to visit. They were happy for someone to see that they cared, that they remembered. I was left alone looking at the commemoration Plaque; a youngish woman approached me. She told me her father had been at the camp and that he had promised to keep something for one of the girls. She felt I should have it. She unwrapped a red lace handkerchief, and inside was the powder-puff case.

* * *

- No way! Sounds too unbelievable to be true! And you bought it all the way back here ... wow.

- These little stories are not so unbelievable, not compared to the unbelievable things that went on. These things, these little stories, coincidences, these little fates are our hope, our reality, our faith if you wish.

It was by no means easy. I had to hide it in my knickers again. The communist authorities were always suspicious of anything connected with the war, and often stole things or hid things away, but what half-drunk half-witted jobs-worth would search the knickers of an old woman like me?

She giggled.

- So, I took many train Journeys once again with the Case hidden. But this time the Journey was home.

But you must understand that at that time people were reluctant to speak about the war, the past.

After the Revolution in Czechoslovakia my husband who was a great traveller went back with me to visit my mother's resting place and we put an urn with her name on it. Quite a few villagers came and stood with hats in their hands.

And I stood with them, with the powder-puff grasped tightly in my hand.

01/28/2018

06:12:17 AM