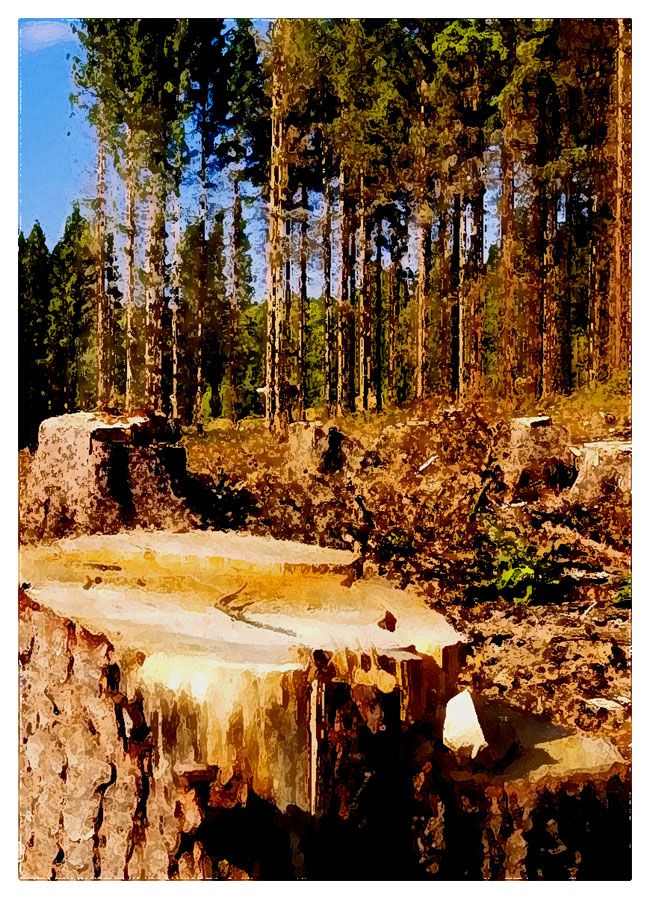

The forestland in Bridgeden, Vermont had eroded since the logging. Each spring, the snowmelt and the rain sent streams of mud down the denuded hills, damming and browning the brooks and killing the young trees that tried to reclaim the land. People who visited the former forest -- campers, cross-country skiiers, hikers -- saw it scarred and defaced beyond recognition, a landscape of dead stumps and bare dirt. Its wildlife had dwindled; once many and healthy, its deer were seen sick and thin by the woods' edges. Shocked by the changes to the forest, people throughout the town rallied: environmentalists, recreation enthusiasts, nearby farmers, and ordinary residents who had not pictured the severity of the damage done. Together, they drew up plans to redeem the defaced earth, to stop the mud oozing from the land, and to save the wildlife. They formed a group that demanded the timber company that had cut down the forest fund a project to restore the woodland. They learned the company had gone bankrupt and could not be made to pay. However, the people were not daunted and directed their calls elsewhere. In growing numbers, they complained to the town government that had sold the timber rights; they went to the state legislature. Finally, their leaders listened and funded a restoration of the Bridgeden woods.

The workers who were to restore the forest arrived on the land on an early July afternoon. There were sixteen of them, ages twenty-one to fifty, mainly from Bridgeden and the neighboring towns. They included Fred Thompson, a husky former farmhand who loved the forest vista beyond the field where he had picked turnips. There was Abbie Miller, a clerk who kayaked the river that ran through the forest every free summer weekend she had. They included John Sparta, an engineer who sought escape from his office by visiting the bird-rich enclaves of the woods that had not been felled. Hired to restore the forest over the next two months, they came to camp and live on the land they would restore. They came in their 4x4 pickup trucks, station wagons, and Jeeps that they parked by the land's edge to avoid eroding the soil. They unloaded their equipment -- shovels, buckets, hoes -- and lugged them in hand and on backs to the camp site, an enclosure within the ravaged woods. Women with the Bridgeden Town Works brought clippers and long-armed pruning shears. Two barrel-armed youths carried in the huge, plastic trays honeycombed with baby pines. A group of outdoors men brought chainsaws, chains, wood chippers and moving carts. Crew from the Bridgeden Roads Department drove up in yellow backhoes and debris storage trucks. The designated camp cooks, Jack Hulston, an affable, stout man, and Renata Wooden, a gregarious, brown-skinned elder, toted in grills, kerosene burners, coolers. The workers pitched tents in the open field by their tools and supplies, creating a literal colony.

Martha Sorensen was a worker from Bridgeden, a woman in her mid-forties with a careworn face. Her plaits of red hair and a heavy pigtail coiled on the back of her neck. She moved slowly in her heavy-set body, her cheeks sagging. Sadness showed in her sleepy blue eyes. As she surveyed the broken, cleared forest, she considered the violence that had happened to the place, the number of trees cut and wasted.

Kevin Hawks was another worker from Bridgeden. He was middle-aged, lean and rugged, an outdoors man. He had sharp, dark eyes, hard-set lips, a head of pale blonde hair. The shape of his chest and shoulders stood out within his checkered shirt. Kevin studied the broken, timbered fields near the camp with a wistful face.

* * *

Martha Sorensen bent, picked up a twig from the timbered land, and dropped it into the satchel hanging by her hip. Broken twigs, branches, and stunted sapling trees cluttered the old forest floor around her. Martha and three other women were moving through a field by a short, brown hill and collecting debris in satchels. Every so often, they went to the collection truck off the field and dropped their refuse in the back. At times, the women broke and carried away the invasive saplings that had taken root in the timbered place; these were thin and the women removed them easily. Martha felled a thicker one with a small hatchet. The hot day made her sweat and reddened her face.

Jodi Greene worked near Martha on the field. Jodi was a quiet woman who had light brown hair and pale, green eyes. The wife of a Densville farmer, she had loved the forest as a child. "I used to see the sun come red through the pines on the ridge at dusk," she told Martha as they uprooted an invasive tree. "I want my children to experience that again here." As they talked, Jodi told Martha about life on her farm in Densville. Jodi said she awoke before the sun to tend the cows and pigs, and to make breakfast for her family and their workers. "I help maintain everyone," she said, smiling. She said that after eating breakfast, she always went to check on their fields, then returned to the house; depending on the day, she went into town to buy goods. Her life turned around these daily activities. Jodi knew what she would do and went at it without question or doubt. Martha considered it was much different than her own life ...

The summer when Martha was twenty, she was Phil Hutchins's girlfriend. Tall with thick brown hair, Phil courted her through the warm, sunny days; they went on rides around town and had long walks hand in hand; he left playful notes on her car window. In one of the high points of that magic period, he had brought her to the forest on a moonlit night. "Let's go in here," he had said, leading her off the trail they had walked. They came to a soft bed of pine needles where, quietly, they undressed and lay together. The forest had always seemed a place meant for Martha, but that night made the forest wonderful for them both. She and Phil married the following autumn.

The newlyweds lived in a room above the general store in Bridgeden their first years. With a young couple's freedom, they enjoyed themselves in nights out with the other young people in town. "Let's me forget being poor," Martha had kidded herself. But she was hoping for a long, happy married life. Phil worked as a builder with a friend's construction company; Martha had a part-time job at the local electric plant; they seemed to have the ingredients for future success.

When their first son Greg was born, Martha assumed they would move into a house. The new child would need space to run around and grow, she thought, and they had saved enough to put down on a home. These plans found their first difficulty when Phil told her that he was thinking to start a construction business.

"I know how to build and people who will want homes," he said. "I can get guys who are good builders to work for me. The business only needs money to get started. Part of it I could borrow from the bank. The rest would come from savings."

Martha stared. "Then what about getting a home now we have Greg?"

"We can delay it a little. Once I get my business going, I'll make enough that we can get any house you want. I might even build it myself."

"The business might not make money."

"It will. I'm a good builder and can make it work. I did say I know people who'd love if I built them their home."

"But do you know what we pass up not buying a house now?" She paced the words to drive home her point: "A sure, certain place. Like Alice and Ted have."

Martha and her husband talked, then argued over the idea of a new home over the next several weeks. It became a continuing event that did not end when they watched the TV, ate breakfast, or tried to share the bathroom. Phil barked; Martha cried out. More often than not, the two parted in cold silence, Martha struck dumb by the hostility they showed.

At last, Martha had to speak with Phil about taking Greg to the doctor. As they reached agreement on when the three of them should go, Martha announced she was tired of fighting over the new business and would not do it anymore. Then she admitted, "I don't mind so much over your having a business as never getting our own home. I wouldn't argue if I saw my way to a house somehow."

Phil suddenly became gentle with her. "I can understand." He said his idea for a business should not mean they had to go without a house. The two came to a level again. They decided Phil would continue at the construction firm another two years and save more money. Then they would split the savings and put half toward a house, albeit a smaller one than Martha desired, and the other half toward Phil's new business that would employ part-time, not full-time, helpers. Happiness seemed to return to their marriage once they settled on the plan. But a sort of worry lingered with Martha when she considered the anger they had revealed to one another and might show yet.

* * *

Broken, smashed tree stumps crowded the land around Kevin Hawks. They stood rotting, gnarled and moss-covered. Kevin Hawks lowered his backhoe bucket into the dirt around one and lifted it upward. He brought the stump to a wooden bin nearby and dumped it. Two men at the bin rattled the sifter beneath the bin and shook the dirt and pebbles free of the roots. Kevin and his team removed several stumps from the field through the morning. About one o'clock, he stopped and went by the woods that still stood near the field's edge to eat lunch with Craig Johnson, one of the sifters. Chuck Tolland, the other worker, carted the stumps to the collection area.

"They did a job on this place," Craig said when they were alone. "Looks as bad as they say in town."

"You never got to see the old forest." Kevin was forty-two, twenty years older than Craig, who was born when the forest was cleared. "Do you know that there used to be pine trees, eighty to ninety feet high? The sun hardly reached the ground because of them; that kept the woods cooler than anyplace around here in the summer."

"Did you like to come here?"

"When I was real young and some in high school. But it was hard after my friend Hal died."

"Your friend die here?"

Kevin looked into the field. "I'll tell you how it was. Hal and I came with friends to drink here one night. He had never been drunk, but he wanted to be. Our friend Jim brought two kegs of beer, and Hal started drinking from them and kept at it. Hal was a thin, weak guy and all that beer hit him very hard. I saw it by how he stumbled walking. He didn't look like he felt too good either, but he tried to act as if he was. I worried about it a little, but I thought if I spoke up, it'd sound like I didn't want him to have fun. Well, Hal was going for another drink this time and fell on the ground. When he didn't get up, a few of us went to him. Then we saw he was dead."

"Boy, that must have been tough."

"Sure was." Kevin fell quiet as he studied the ruined timber field. He hardly talked about Hal with anyone.

* * *

On a dark, hot July evening, the crew of workers gathered around a campfire to eat their dinner, hungry from the day's labor. They spoke in short clips and low voices for they were still new to one another. In the uncut forest nearby, thousands of crickets chirped without end.

* * *

After clearing their first section of land, Martha Sorensen and the other three women on her crew headed to an open area the timber company had not touched. Invasive ferns had spread there from outside the forest and covered much of the place. Martha and her crew were supposed to pull the invasive plants while sparing the native growth. The women spread in a loose line to walk the land as they labored. At times, Martha watched the other women bend as they plucked and bagged. Jodi Greene, the nearest her, bent and rose with a energetic turn of the shoulder. Her face grew red and wet, but she toiled without flagging. I wish I had as much energy, Martha thought. She knew she often had not ...

When Martha's husband Phil started his construction business, he employed helpers only part-time as he had promised; this meant that he built his first houses largely alone and over many, long days. As he kept busy at it, Martha settled into their new, small home. She spent many satisfied days watching her sons, Greg and Jason, play and run through the house and on their new, wide lawn by the river. I've become like a child with them, she thought, as she threw the boys a ball as part of some game. She would have been happiest if Phil's work had allowed him to be there with her, but she knew his business made it hard. To manage with her kids, she arrived home mid-afternoon from the electric plant with Greg from school and Jason from day care. She never expected Phil home until nine.

Then Phil started to go on trips a couple of times a month related to the houses he was building. "I went to see a house these people asked me to model," he explained once. "It was way out of town, so I holed in at a motel rather than drive back at night." Another time, he informed her that he had gone to investigate a lumber supplier upstate. "Wood is cheaper there," he told her, "but it takes awhile to get the best deal on it." During his weekends away, Martha considered how Phil must be bargaining with lumber merchants and retailers, far from the family. I bet he doesn't think of me, she assumed more than once.

* * *

Kevin Hawks and his two helpers Chuck and Craig had removed most of the old stumps from the field and now were after the last, the very fat, well-anchored ones. Kevin brought the backhoe upon an old hunk of oak near the field's edge. He dug with his bucket on one side of the stump, then another, before he managed to raise the thick mass about a foot. Chuck and Craig chainsawed the roots still holding the wood to the earth, and the backhoe pulled it free. Kevin laid the hulk on its side, exposing the oak's black rotten bottom to the air. The sight of the exposed roots repelled him and made him uneasy.

As he grew into an adult, Kevin knew fewer of Bridgeden's people to go into their forest. Kevin had felt it strange at first. He enjoyed, as ever, coming to the woods and hiking the trails even after coming to terms with Hal's death. But the people of town had found conveniences that occupied them more than visits to the woods ever seemed to do. Families gave up their rambles in the forest land; they kept home watching DVDs or went shopping at the new strip malls of the area. Those who had barbecued at the sylvan picnic grounds did so now in the backyards of their new homes, created in the town's widening sprawl. Kevin's younger friends hit the town's Cineplex and diners and never mentioned the woodland anymore. Little by little, Bridgeden came to think its forest a place beyond its world, only dark lines of trees by the roadside.

Then one day, news came of a timber company in Boston interested to buy the entire forest from the town of Bridgeden. Its meetings with the town officials got reported in the local media. "Your forest seems not to be doing much for you," a company rep was quoted as telling the town aldermen. "Sell it to us; we'll give you five percent of the profit on the timber." The aldermen were eager for revenue -- to build their own benefit packages as everyone suspected -- and all but promised the sale; they held out only for the perfunctory approval of the town boards.

When word spread of the company's plan, several of the more high-minded Bridgeden residents raised an outcry. In forums around town, these dedicated persons urged Bridgeden's people to stand up for their forest. "Our town has a responsibility, a duty to protect natural spaces of wonder," an environmentalist with the group claimed, banging her fist on a podium. The forest activists pulled together a small, vocal group who proved insistent and emotional at the new official meetings on the company's proposal. In galleries at the town hall chambers, they hoisted signs with the words, SAVE THE WOODS and PROTECT OUR WILDLIFE, in blood red. However, the town boards were too satisfied with the idea that selling the forest would benefit the town's bottom line more than leaving it be. "We can't stand in the way of progress for Bridgeden and its people!" said a town alderman, trying to sound urgent at the decisive meeting. The town boards approved the sale, but the activists cried and rallied against it to the end. They received finally a small concession: the town would retain a quarter of the woodland. "To preserve at least part of the old wilderness and its character," as the official notice proclaimed.

Kevin Hawks had worked for the Bridgeden Public Works Department as a landscaper while the debate on the forest sale raged. He had sympathized with the activists for the forest but kept his opinion quiet, fearing for his job. Later, he felt guilty over it.

Chuck Tolland chainsawed the black, uprooted oak hulk Kevin had pulled up with the backhoe. Once done, he fetched a wheelbarrow lying nearby and hoisted the cut wood inside. Kevin saw how hard Chuck had it to lift the old oak masses. He parked the backhoe and went to help him.

* * *

Rain fell on the uplands where Martha Sorensen and the other women picked up loose trash. The earth was muddy and oozing under them as they worked. Their satchels fattened with the old aluminum cans and broken glass they discovered in the ferns until it forced the women to slow. Martha became aware, as she had many times earlier, of the regular movements to their labor. The women moved in a rough line up the hill, one never going far ahead nor staying far behind the rest. Their torsos bent as they searched the ground; one rose to stretch as another bent to pick. Discovering this rhythm in their movement gave Martha energy as she labored beside the women.

Midway up the hill they walked, Jodi Greene slid and fell down a stretch of wet stone. Martha and the women rushed to her and found she had cut her forearm and lower leg. Their colleague Cheryl Jackson came with iodine from the wood side and treated the injured woman. With another worker, she led Jodi back to camp to rest and recover. The other women returned to their satchels, voicing their hope Jodi would be okay. Martha went on with her work, rattled over her friend.

* * *

Phil had to miss his son Jason's seventh birthday because of another of his overnight trips. On that Saturday in April, Martha was alone with the boys and with nothing better to do than watch TV. Before the set, she moped as she thought how dissatisfied she was in her marriage. Phil had stayed from home more weekends than she could remember. Maybe I'll never again be happy with him like the summer before we were married, she mused. Her disappointment lingered, and she decided she must do something to feel better. She fetched her coat, told her sons she'd be out, and drove to Densville. She planned to visit a spot by the river where Phil had taken her to see red columbines in the spring before they wed. Maybe I can go and find an early flower there, she hoped.

Martha drove the route to Densville with eyes floating dully over the road. As she passed a stretch of the old woodland, she saw a beaten up, blue house by the roadside; in the driveway was her husband's red truck, its tell-tale, weathered black and green flags on the antenna pole. What on earth is he doing here? she asked. She slowed her car and turned into the driveway.

When Martha walked to the house door and rang the bell, a young, thin blonde woman answered the door. She was in a bed shirt, short shorts, and slippers. Martha stared in disbelief.

"What is it?" a male voice said from inside the house. Martha's husband appeared in the foyer clad only in a pair of jeans. He froze before Martha who stood blank faced, disillusioned ...

Back home, Phil told Martha everything. He had met Jennie Anderson, the young blonde, a few years ago at a local pub and since seen her under the guise of his weekend business trips. Later, he had made excuses to Martha, saying he had to finish a house, and met Jennie even in the week. They had gone on several years so. "I think I would have continued at it, too," he admitted, his voice humbled.

Martha listened, her pain expanding, as she remembered his many acts of avoidance, his brush-offs of the last several years. "I only wish you had said this sooner," she said. "We might have repaired things."

However, she felt the damage done now and irreversible. She could not stay with a man who had gone behind her back as much as he did, so divorced Phil. She took their kids and her share of their belongings and moved into an apartment in the business end of Bridgeden. Starting over again when I'm this old, she thought sadly, installing her bed in the apartment's smaller bedroom.

Soon into her transition, Martha lost her job at the electric plant when a regional utility bought her employer. She sought new work while doing day labor at farms in Bridgeden and the nearby towns. She had been a farm hand before marrying and, while it felt arduous taking up the role again as an older woman, she found she enjoyed many parts of it. She liked the low, easy rattle of the cart she pushed to the fields, watching the sacks fill, seeing the hay she forked bundled into haycocks. Slowly, an appreciation for working in the open air took root in her.

* * *

Men came with digging and earth shaping equipment to the hill where the women collected refuse in the rain. After he parked his backhoe, Kevin Hawks walked up the wet terrain to Martha Sorensen who stopped bagging and greeted him.

"So, you guys will be terracing?"

"Bit at a time." Kevin studied the hillside. "People sure bust up this place. You know, we can start to fix it, but the land does the real recovery by itself."

"Yes, it does."

"Everyone will have to respect the place more for it to have a chance."

"Maybe enough people will since the timbering."

"I hope."

The two studied the ferny area around them that was to be shaped, then walked from each other, touched by a sense of resolve.

* * *

At last, the workers removed all the broken, rotting tree stumps from the ravaged land and all the invasive Asian trees and spotted ferns that stole water from the native species. The teams took away all the aluminum cans that had been thrown into the bush, all the plastic bags, all the broken stone left by the timber company. The earth in their wake lay pockmarked with holes and torn into newly upturned terraces.

On a newly open expanse, the women kneeled, their knees pressed into the dark, cool dirt beside the trays that held the baby trees to plant. The women scooped easy holes in the turned land, laid the plants inside, and packed the earth around the babies' roots. Near the infant trees, they planted native ferns to hold the earth firm so it would not erode. The women smelled the broken soil in their hands through which small beetles and worms wriggled.

Martha recalled that she had visited this part of the woods with Phil and young Greg long ago. By then, most people in Bridgeden had lost interest in their nearby woodland. However, Martha brought her child certain she could inspire him in the place. She and young Greg had craned heads up toward the tall pines in the wood and saw the pattern of dappled light in the boughs. At one point, she took a fallen pinecone from the many on the ground and put it in her pocket to give her son when they returned home. Martha smiled as she covered a baby's roots in the ground before her. The forest will return when these trees grow tall, she thought.

* * *

From the large heap by the wood side, Chuck Tolland fetched several thick pieces of pine and forced them down the chute of the wood chipper. The ready machine growled into life, and red chips erupted into the catch bin at the other end. Once all the pine was ground and the machine silent, Craig Johnson, who had held to the side, sifted his gloved hands through the new chips, breathing in their wood smell. Kevin Hawks lifted the bags of chips that Craig filled and carried them to the back of their truck. He knew his two companions were eager about grinding down the old wood. Chuck had said that morning he wanted to see an end of tree stumps, and Craig bagged the rich, scented chips without help even after long shoveling. Thinking of their good mood encouraged Kevin as he labored slowly beside them.

As the chipping went on, Kevin saw a scratched piece of oak amid the heap awaiting the chipper. The scratches, perhaps done by bear, made Kevin remember when he and his friend Hal had come to certain a tree their first time in the forest. The tree was marred on the black bark near its base and the boys had fingered it slowly, moving their hands with a kind of awe. Hal took his pocketknife and carved his name in rough letters over the marks, and the two had studied the new cuttings silently before leaving. Maybe those are the same scratches from that tree still showing after all this time, Kevin thought. He looked at the men moving easily at the destruction with the chipper. He thought that, if he took the scratched wood and kept it by his side, the other men would ask why. He disliked the idea. Hal and I, he considered, we never talked about cutting that tree. So Kevin let the wood piece alone, his eyes turned down toward it. The men at the woodheap kept at their labor.

* * *

After finishing with the baby pines on the hill, Martha and four women planted wildflowers in a spot where they had pulled invasive ferns. Martha kneeled on the ground to plant trillium in a group of eight, red and white, as the women around her planted merry-bells and red columbines. She planted small bluets and asters alternating for the contrast in the color. As she worked, she remembered when she had seen the original wildflowers of the place as a little girl on a school trip. The low, little trillium with its pointed petals and the tiny violets had excited her and she had dashed along the path where they stood, her red hair blowing back. She was laughing by the time she came to the dark, tall pines, and her teacher had yelled that she stop. It had been easy to love the flowers, Martha thought, the way a child can love on the instant. She felt much time had passed since she would have been excited over their splendors. Her body had thickened, her muscles lessened; life had worn her. And yet it did not stop Martha from feeling good she planted the new flowers. During the lulls in her work, she re-imagined the scene of her former happiness, the flowers everyplace she had run.

* * *

The fence, all that remained of a farm kept one hundred and fifty years earlier, was a sight that hikers once spoke of in town, a solid assembly of granite, basalt, and feldspar stones. Kevin and five other men were to rebuild the parts the timber company had knocked down when moving its power equipment. Most of the tumbled stones lay close to the fence, so it was relatively easy for the men to seize and re-set them. They arranged the stones now so the gray and blue mixed with yellow and white. The men fitted short stone beside tall, narrow beside thick, rough beside smooth. They laid each layer neat and flat on the rising wall. The men called to each other in their good mood as they worked.

Kevin set a chunk of feldspar firmly atop the fence. When he spied the bright flecks in the flat stone, he remembered when he had seen the fence for the first time when he was ten years old. He had come wandering through the woods that autumn day to fish the nearby stream and spied the stone wall by accident. Because the wall blocked his view of the other side of the woods, he climbed onto its top to see over and from there discovered the forest spread over the flat land a quarter mile around him. He saw the autumn trees overlap far into the distance, their leaves colored like fire; he felt the wind blowing through them, crisp and brisk. The sun lit the scarlet maples, and the sky showed a strong blue overhead. However, there was much dark and dying in the place, too. There were bare branches in the trees; on the ground, rotting logs covered in lichens. The few passing clouds hung fat, gray and heavy though they carried no rain. The clear and the gray, the bright and the decay together had made Kevin feel both excited and quiet, serious and happy. He thought it right to respond to the forest like that because the place was not just one way. He had felt it curious to think but real.

* * *

The workers gathered around the campfire at night and talked of their labors in the woodland. They sang a song of the beautiful place they were saving.

I love the mountains, I love the rolling hills

I love the flowers, I love the daffodils

Martha Sorensen let her voice rise as she sang to encourage the rest, for she remembered the path she had run as a girl. Kevin Hawks sang more quietly, for he remembered the scratched wood he had let go to the chipper.

* * *

Two months and a week after starting, the restoration crew finished creating its new forest of infant trees and fresh flowers. The workers had set terraces, rebuilt fence, and laid fresh trails throughout the woods. The men and women celebrated with a pig roast that drew them round a huge, open fire. Everyone shared forest memories as friendly Sue Patterson went with a video camera to record the people offering their stories. She came to Jodi Green who said, "My favorite time in the forest was when I was a little girl and my parents brought me to the waterfall that's in the heart of the woods. These two black and yellow butterflies came flying near the stream there that were just beautiful. I went to touch them, but they flew past the mist by the water. I didn't see them again."

Sue brought her camera next to Chuck Tolland. "Tell us an interesting tale, Mr. Chuck," she said, her eye hugging the camera lens.

"Well," he said, leaning forward. "when I was a teenager, I saw a family of deer in the forest. The doe was far off in the woods they didn't cut. She stopped and stared at me without seeming frightened at all ..."

Cheryl Jackson shared this account: "I had the best thing happen the third day here. When I was done pulling all those ferns, I went to a lookout by that hill a mile away that showed the old forest where the trees hadn't been cut. The woods were so green and covered three or four hills. I was glad to find it when we had everything still to clear."

Sue finished recording the many stories and announced that she would put the video on YouTube where they all could "retrieve their fireside memories anytime." The roast ended; the workers packed and loaded their goods and belongings into their trucks and cars. Since most of them lived in Bridgeden or close by the town, they promised to meet in the coming weeks. The whole crew had become good friends and meant to continue so.

Martha Sorensen was among the last workers to leave. While Jodi and another woman waited for her by their trucks, Martha went to a hillside planted with the many baby pines and young ferns and imagined how the land would be when the trees grew sky-tall. Kevin Hawks also held back from going. He had his friend Chuck wait while he went to the new terrace they had ploughed. The new pines, ferns, and flowers planted there sprawled before his feet. It made him think the land ready for a future.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.