There is a route you follow at work, picking up rubbish and the things that fall off exhibition stands. The other cleaners just empty overflowing bins, moving quietly down narrow corridors behind the stalls. They’re too old to be doing with all these pushing people, they tell you.

That’s not why you’re here, though. You don’t want to hide behind stalls or empty rubbish bins. You walk up and down the aisles collecting papers and plastic cups. You are quietly helpful, accumulating rogue mobiles and nametags, bringing them to lost property. You brace wobbly display cases while exhibitors stuff folded napkin shims under the legs. People thank you, without expecting a reply.

Which is good. Because they wouldn’t get one.

You drift up and down aisles, past excited people at Comic-Con or Gardeners’ World or eCommerce Expos. Past people chatting with friends about tattoos or jewellery or Pakistani property. You learn by osmosis, soaking up their enthusiasm. You feel less alone. It’s why you took this job, after all.

This week, it’s Costumes International, exhibits showcasing Japanese kimono, German lederhosen and dirndl, Korean hanboks, Nigerian dashiki. There is a stall with nothing but crimson-coloured fez hats. There is a stall covered with beautiful, angry wooden masks glaring down from cloth walls. Some are old, expensive. Others are new, brightly coloured. Buy them now, jazz them up, wear them to next week’s Steampunk Convivial.

People chatter, speaking RP English and heavily accented English and languages that flow like water across your mind, unbroken, impenetrable. You are turning away from a group discussing sari fabrics, holding some crumpled napkins symbolically in one rubber-gloved hand – you are working, see? – when you spot him.

He is alone, moving like a soft fog, drifting down the aisle. He gazes momentarily at each stall, collects cards and leaflets. He stares down the masks, his face a matching scowl.

You can’t help but follow him, his large frame, his silence, his concentration.

You bend to collect some fallen keys, add them to the pouch of things for lost property. You push a stack of booklets back from the edge of an exhibition table and the owner nods her thanks at you. You keep him in your line of sight.

Your heart is leaping, you can feel it in your throat. Maybe it’s butterflies that you’re feeling. Maybe you’re having a heart attack.

You dodge around groups of people, watch him from behind a display case, feel punch drunk, slightly giddy. You don’t know why you’re following this silent, staring man. You are here for the noise and interactions with strangers.

What would Ma say? Or Jeff, two years younger and full of all the bluster you lack, but kind and loving. Would they laugh at you for chasing this ghost man? Scold you for creeping? They are the only ones you can talk to without st-st-st-stut-t-t – stuttering? people autocomplete for you – without clicking and blushing your way through sentences.

Doctors said the stutter would improve as you got older. Speech therapists got annoyed with you for not working harder. Teachers thought you were dumb. Classmates who had been kind as children stopped caring about you once you moved to the big secondary school. You left at 16, couldn’t take the try harder and he’s just stupid and it’s not like he can tell anymore. Ma said that was fine. They would find something for a quiet boy who likes to be around people.

Just because you can talk to Ma and Jeff, doesn’t mean you tell them everything. Like about the kids who used to steal your stuff because you couldn’t tell a teacher. Or the men in clubs who never ask a single damn thing, just offer you a drink and a shag in the bathroom. Some things you can’t share.

You are nearing the food area. This isn’t your patch. Harvey claimed it on your first day, four years ago, fresh out of school and still forcing yourself to stumble through sentences squeezed out of your mouth like ricotta through a tube.

“Dis my area,” he’d gestured towards his domain, his little kingdom. “You stay ’way.”

“O-ok, sh-sh-sh…” But he’d already turned to collect a fork off a plastic table.

You stop pushing your little cleaning cart, wait for a cluster of giggling women to pass before turning away from Harvey’s patch. A wave of loss crashes over you and your stomach twists. The ghost man will go one way, while you head back to where you came from.

But the man stops. He turns to face you, looks directly into your eyes. He tilts his head slightly to one side.

He stands and stares for a second or ten. Maybe it’s for an hour. Or a lifetime.

Then he gestures, waves you over, makes the universal gesture for drink, tilting his hand towards his mouth. You nod, numbly, dumbly. He points at a table and turns away. You sit, hoping that Harvey won’t scurry over and tell you to go ’way. It’s probably break time, or lunch time. Time moves oddly in the convention centre; you can never tell the time without looking at a clock. But you can’t tell Harvey to piss off, so, you quietly pray he doesn’t notice you.

The man comes back, holding two cups, his pockets bulging and his bag slipping off one shoulder. You leap up, following the rising path of your heart in your chest, and grab a cup, smell the hot chocolate as it sloshes, just before the strap slides down onto his elbow jolting his hand. He smiles, then sits across from you.

You open your mouth, then shut it. What could you possibly say? You try again.

“Th-uh. Th-tha…”

He shakes his head. Your face reddens, and confusion crinkles your forehead.

He shakes his head again and smiles. Then he points at one ear.

You realise. He is deaf.

He makes some complicated gestures with his hands, and you shake your head in return. You don’t know any sign language, though you suddenly wonder why not.

He raises a finger: wait. He roots around in his bag, pulls out a notepad and pen, lays it on the table. A notepad. And a pen. Open lines of communication.

Hi, he writes, then slides the pad across to me.

You don’t know what to say. It has been months, maybe more, since you’ve talked to anyone besides Ma or Jeff. You hold the pen awkwardly. It’s been a long time since you’ve written anything either, you realise, possibly since school. You feel stupid.

But you look up, and the man is smiling gently, patiently waiting.

His letters are sloppy, quickly written. You wonder why he doesn’t just talk. You knew a few kids at school who were deaf but spoke, in a flat way but still with an accent – how did they get an accent if they’re deaf? – but this man just sits, and smiles.

The pen touches the paper. Uhm. Hi?

Hi there.

You don’t know what to write next. But he doesn’t rush you, just waits.

You look different to the other people.

I do?

You’re not with a group. Or shopping. You look busy, tho, like really focussed.

The words begin to flow. You can write as you think, and even when you get things wrong you don’t stop.

He nods, then replies.

I’m here in a professional capacity.

Me too.

He laughs. His voice is deeper than you expected, full in his chest, and his face splits into north and south lines.

You still have the notepad, so you ask what he does. He scrawls across the paper, explains that he works for a museum, and also with the government. Repatriating artwork, locating items that we stole from countries back in the heyday of colonisation when we would steal their art and their costumes and their people. He says there are still people who profit from that, and sometimes they set up shop in conferences, selling things they shouldn’t, sneaking priceless items in between tat, selling to discerning buyers of illegal goods. He finds the good stuff, catalogues it and who is selling it, collects business cards, puts it all in a database. If there are enough hits on a person or place, they get the police involved.

So you’re a detective?

Sure. I mean, I detected you watching me right?

You flush again, but nod and shrug and nod. You take a sip of hot chocolate, cheap and sweet, a place to hide your face.

It’s ok. I was just wondering why.

You don’t have the words for this. This isn’t easier on paper. Even if you could say it, you wouldn’t. How can you write the words chasing themselves around your head, words like beautiful and fascinating and incandescent, stupid words and big ones, words you barely know and can’t spell. Words that wouldn’t explain, really, why you felt compelled to follow him up and down the aisles of a convention centre.

I dunno. I just –

Harvey suddenly appears, scowling. “Boy! You in my patch. You gotta work!” You jump at the interruption, while he gestures toward the stalls.

The man – you realise you still don’t know his name – waves at Harvey to get his attention, says in his deaf man’s voice, “I needed help, and he is helping me. Thank you for understanding.”

Harvey stares for a heartbeat, then shrugs at the man and glares at you, and wanders off muttering about making sure we clean up our own table.

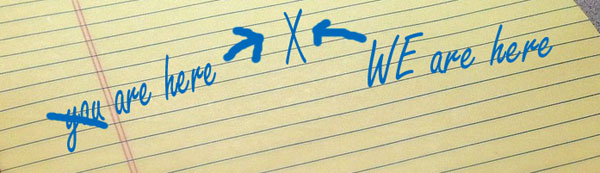

Thank you, you write on the notepad. We are on our third page, a whole conversation in blue on yellow. Also, btw, I’m Alfie.

He laughs again.

Names. Derp. He actually writes ‘derp’ and you feel your chest expand. Can you fall in love with someone because they write a word as ridiculous as ‘derp’? I’m Leto.

Where’s that from? Is it from an African country? Is that why you got into the repatriation thing?

He says it’s not; his parents were just massive nerds and it’s from a sci-fi book. He says he got into repatriation because of his grandmother, who remembers her grandmother who lost everything when she was transported. He remembers his grandmother, crying in the middle of a museum staring at masks and figurines, so out of place, lonely in their cold case so far from home. He says he was maybe eight. Those tears changed his life.

He writes, Enough about me. Tell me about you.

I got nothing to say. Nothing like that.

But he waits, smiles his patient smile. So, you think, and you write, slowly.

You tell him about being a kid out of place at school. About having no friends but your brother, about wanting to be with people but no one having time for you to get through your awkward sentences. About feeling like your mouth is always filled with gravel, your voice always stuck like bluetack in your throat. You write that you left school early, even though you liked it, because they thought you were dumb, and no one let you take things slowly. You write that you got this job because Jeff came with you to your interview to be your voice, and because they would have taken literally anyone, and because it means you can be around people.

You write that you wish someone would repatriate your voice. You don’t know when it left, but you haven’t talked to anyone besides Ma and Jeff in a long time.

That’s your life, right there on a single page in your small, cramped writing.

He is next to you, reading as you write. He smells warm, slightly sweaty, and also like soap. You probably smell like cleaning products, lemon astringent and rubber gloves. You hope he doesn’t mind.

He picks up the pen. You’re talking to me, right now. I hear you.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.