On Detective Eli Feliz's thirty-third birthday, he was called to the basement of Dr. Attic, a literature professor found murdered in Queens, NY. There was no sign of forced entry, and the only recoverable weapon was found lodged in his back. The knife belonged to the Antiquity Department, and it had gone missing a few weeks prior. It was used during the Mesopotamian age, particularly amongst Jewish tribes, and for the act of lamb slaughter. This murder belonged to a string of Jewish murders, and there was no telling if they were at all connected, though the human brain had a great faculty to recognize patterns.

This would be the first case Detective Feliz almost solved. All the others had been obscured beyond recovery, with mediocre criminals free only as a matter of rotting Chance. Perhaps if the almost-solved case had occurred a year later, he might have discovered the criminal with adequate evidence to imprison him. But Chance was still breathing in ‘69, and you really couldn’t do anything about it.

Dr. Attic was Jewish by birth, and an atheist by culture. His mother was a zealous Christian, bordering on Fascist, and enjoyed pestering Attic about his atheism. The weekend of his murder, she had gone up to Olean for a church retreat and had left Ricarda the housekeeper in charge. The mother shared her suspicions about her. She was, of course, their first suspect.

When they received the call on January 30th, they were surprised to hear a well-spoken woman of Hispanic descent. She told them that the boss’s son was bleeding out before her, and, as far as she could tell, was muttering Hebrew to himself—the Shema, to be exact. As Detective Feliz approached the basement door, his partner, Detective Duermo, ran up to him, asking him what they would be doing there.

“Are we going to arrest her?” Duermo asked, sighing at the thought of paperwork. “It’s obvious that she killed him. You don’t need two detectives to figure that out. Hispanics hating Jews is nothing new.”

Feliz, before pushing the door open, examined its frame, reconfirming what he was told about the lack of a forced entry.

“It’s simple thinking to affirm stereotypes,” he began, “and you of all people should know that.”

“I know what I know because I am one, obviously, without the anti-Semitism. You can’t go one block without a muttering about the Jews. It’s just reality. But I didn’t mean her, I mean, maybe her. Maybe she’s innocent. Maybe she loves the Jews. Maybe it’s that simple.”

Feliz shook his head and said, “Reality is far from simple.” Duermo laughed at him for the fact of his constant cliches.

Ricarda was sitting on a basement step when they entered. She was fidgeting with something in her pocket and weeping simultaneously. At the sight of her tremor, the detectives asked her to stand up, walk slowly towards them, and hold her hands high.

“Please, sirs,” Ricarda began, holding back tears. “I found this letter on his body. I picked it up because I didn’t want blood on it.” She handed them the envelope.

At first, tempted to reprimand her for having removed a piece of evidence from the scene, they chose instead to undo the sealed envelope and read the letter to themselves. The following had been scribbled upon it: Ricarda is a Nobel Prize winnings, whom wrote five total novels is writing now, one now! It concluded with a poorly signed Gustav Attic.

The two detectives looked at each other and reached for their subsequent cigarettes.

Duermo was the first to break the meditations. “Is this some kind of joke?”

Ricarda looked up at him and began to tremble. “What do you mean, sir?”

“The letter—are you messing with us? I mean, you’re telling me, that a literature professor, devoted to words, wrote this down so poorly, and also, wrote it about you? A housekeeper?”

“Yes, really,” she stammered, “I don’t know what to say but I found it there, on him, sealed. He was looking at me, talking to himself, and the blood was everywhere. And I picked up the letter because I didn’t want there to be blood on it, really. You have to believe me.”

Feliz walked around, puffing the gray smoke and scratching his beard. Attic was lying on his stomach, wearing brown pants, leather shoes, and a tucked-in white linen shirt.

There was nothing to help: everything belonged in its reasonable place in a reasonable manner. For example, the rainbow spines of books were neatly tucked; laundry baskets were upright and full only to the brim. The carpet, though obviously in some parts stained, was finely dyed, and not one grain of hair stuck up out of place. The desk was polished and the lamp was on. A Borges collection was open beside a few lined pages and a pen streaming with ink. And suddenly, it struck him: the wet pen. Drawn out on the paper was a blackbird.

He walked over to the desk while Duermo continued to pat down Ricarda. He looked around in the drawers and found erasers, pencils, porn clippings, and apple stems. The chair was a soft brown leather, and he rolled it away from the desk and looked underneath. He jerked back at what he saw, then proceeded to uncover the darkness with his flashlight.

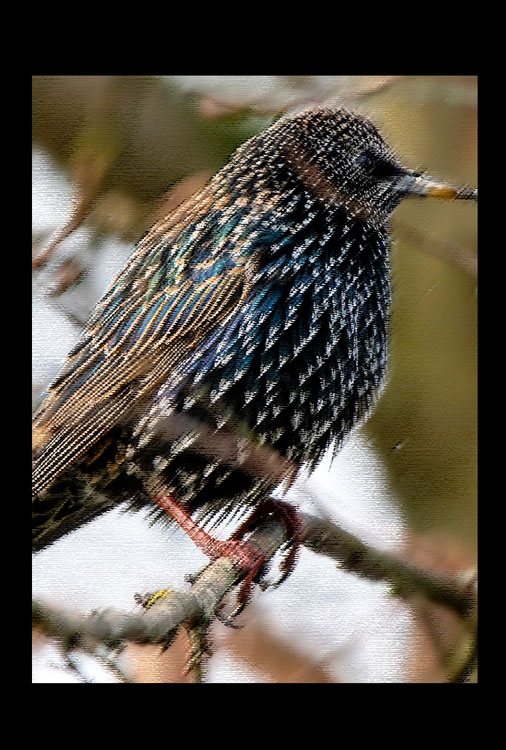

A starling was dead on its side, holding a little note in its claw. As he began to pull the note free, he called Duermo over, adjusted the lamp, and read out the note.

“The Russians know a lot about framing murders. Dostoevsky, for example, is my favorite.”

Feliz immediately stuffed the note into a plastic bag and walked to the bookshelf. Perusing the iridescent spines, he finally found The Brothers Karamazov, beginning to flip through the pages. Towards the end of the book, around Dmitri’s trial scene, he discovered lime-green ink planted on the left page. “Look on my spine.” Feliz looked over to Attic and could see faint black letters under the white linen shirt. He ran over to the body and began to cut open the shirt with his utility knife.

“What the hell are you doing,” yelled Duermo, running over to Feliz. He grabbed his shoulder, though Feliz persisted. And with each revealed black letter, he removed a finger from his shoulder until his hand was completely off and they could read the following: THE SON ARRIVES AT CHURCH WITH A NEW WORK. THE YEAR IS BLESSED AND HIS.

After photographing it all, they decided that they had enough to process for the day. They assured Ricarda that she wasn’t under arrest, but that they would be visiting often to go over the details of the case in order to finalize her involvement, if any. She left quietly, muttering a blessing in Spanish as she passed them. The detectives walked back to their car but suddenly stopped on the grass. Before them were smashed windows and mirrors.

As they approached the vehicle, Feliz looked over to a piece of mirror on the ground and watched Duermo’s face appear. Though eventually he attributed it to the work of light, he could see a grin on Duermo’s face and a purple shade upon his lips. They called for a pickup and made their way back to the station. They would update Cooper and follow up with Ricarda the following morning.

At home, Feliz made himself a whiskey sour and smoked cigarettes. He read from his Edgar Allen Poe collection that he had bought used for a mere five dollars. After an hour, he put it down and went out to the porch to ponder the investigation. There was nothing that could be done, and that was bloody obvious: but one still had to try. As to what he would do, he didn't know: the best step forward was to bother Ricarda and figure out if she was still withholding details. Not much could be done until then, but he devoted most of the night to trying to figure it out, regardless.

Finally, around five in the morning, he thought it best to get ready, make himself some coffee, and head over to Ricarda’s. He didn’t bother calling Duermo because it didn’t hold any significance.

As he drove on, he noticed that Flushing was still drowning with purple night, and a few yellow lights appeared in apartment windows with steady meter. He looked over to Ricarda’s apartment building and parked right in front. The red bricks shimmered with the night’s rain. Smoothing his suit, he walked to her door with measured steps. Someone was leaving the building and held the door open for him. He thanked the old man. Being careful of where he stepped, he finally managed to climb up to the sixth floor. He looked around for her 666 apartment number, found it while noting the rising primitive fear in him, and knocked on her door once. It gently brushed away from him. It had been left unlocked.

He walked in carefully, his hand upon his gun. He called out to her to no response. The bathroom light with its dim whiteness was the only one pouring down the hall. The blender was plugged in and quietly turning with nothing in it. The faucet dripped and the floor moaned with each step. He reached the bathroom and shut the light off. The only other door was closed. He was prepared to die.

He pushed the door open, flashed his gun and light horizontally, unable to see anything abnormal. He reached for his phone to give Duermo a call. Someone had been here, possibly wanting to shut her up, he thought. As he began to dial, groans began to rise from the floor. The bed blocked the source, and he walked around the frame, still holding his phone.

He flinched and grabbed for his gun, pointing and looking around him. Lying there was Ricarda, squirming with little movement, blood escaping her head. She tried her best to look up to him, attempting to convey something through her eyes. The only thing he understood from her poor expression was: I am afraid to die. A moment later, he was yelling into his walkie, calling for an ambulance, and received vain static. Ripping the bed sheet off, he bent low and tried to hold her head. With her head resting in his hands, she began to gasp for breath, and he pleaded for her to stay with him. Finally, with the last of breaths, she managed to speak to him, paralyzing him as a consequence: “The Son arrives at,” and her eyes flickered, her groans stopped, and she was dead in his hands.

He gently laid her on the floor and ran to the bathroom to wash his hands. Withholding the urge to vomit, he rinsed his face and began to hyperventilate. With each splash, a temptation rose within him to pray to God. As he dried off, he succumbed to the maternal tradition. “Please, dear God, give me the answers I need, please, I’m tired of looking just give it to me!”

He walked out of the bathroom and heard Duermo shouting for him. Like a child greeting his father, he ran and fell onto him, allowing himself to cry upon his chest.

“What happened? Where is she, what’s—”

Feliz interrupted, “She’s dead, Duermo, she’s dead, and I tried to get her, to save her, I really tried,” and Duermo quieted him and led him to a chair.

“Do not worry, my friend; there is no such thing as a dead Hispanic,” he whispered to Feliz, “as long as there is evil, there are Hispanics. That’s what I’ve been trying to tell you, Eli, but you don’t listen! What do we have in this world but our freedom? And guess what, when they come over, what happens? They take it from us! And I won’t let them, I won’t. It’s not in God’s will for them to come. And you know what else? You shouldn’t be crying over that damn spick. Enough of it. Wipe yourself and let’s go.”

Duermo reached for a cigarette and sat down in front of Feliz. Feliz looked up to him, wiping his eyes, trying his best to ignore a fiery anxiety growing in his chest. He looked at Duermo smoking so casually, shooting the air with ease, and coughing lightly; noted how Duermo scratched his face and groin without a sense of urgency, clearing his throat when he felt like it.

“Duermo,” began Feliz, his voice trembling, “tell me now. Now, Duermo. Did you kill her?”

Duermo continued to smoke and puff with casual carelessness. When the ash had grown longer than the cigarette, he put it out on her carpet and looked at Feliz.

“And you killed those other Jews, too, right? Not only Attic. The others, but—why, Duermo? Why?”

Duermo coughed and leaned forward. “I didn’t kill anyone, Eli. No one. I’m not a killer.”

Suddenly, he jumped from his chair and shot Feliz in the leg. From impulse, he grabbed at his leg with both his hands, and Duermo took the chance to hit him in the jaw. A dark nothingness soon overcame him and time became non-existent.

When he awoke, Duermo was drenched in the red of an Exit sign. Standing beside him was the old man Feliz had seen at Ricarda’s. Duermo was whispering to the old man as Feliz began to stir awake. A clock above his head read, 11:56. Midnight was coming, and with it, a new year. Noticing his groans, he flipped the lights on and stood before him.

“Where am I, Duermo? Where am I? What have you done? What have you done,” and growing to a scream and now squirming, he continued to yell, “what have you done, Duermo? What have you done?!”

A quick throat punch quieted him down, and Duermo assured him that he would be informed as long as he kept quiet. Bent over and coughing, Feliz attempted to look up at his partner but could not bear his sight. Duermo walked over and combed Feliz’s hair with his hand and even kissed his cheek.

“I’ve never killed anyone, Eli. I made that clear. No one. I’m not a damn killer. But what I am is tired. All this damn searching, all these aligned coincidences. It’s enough to drive a man mad!” He called the old man, Roberto, over to him and began to stroke his shoulder.

“Here, my messenger of God, I asked him to go after someone to do all this damn killing.”

“But who did it, Duermo? That’s all that matters. It’s what I want; what were their names?”

“I don’t know their names,” and he looked down, picking at his nails. “And really, that’s your damn problem. You think you’ll find the answer. But there is none. Even when you pray to God, there’s no answer. There’s only silence. And what could be more quiet than death? And that must be the point of life, I think: living to not know. So, really, living to die. With the dead, we know nothing of life.”

There was an empty chair before Feliz. It seemed like they were in a church somewhere, mainly because there were paintings of white men reenacting what seemed to be Biblical events on the ceiling tiles. On one, he saw Christ walking out of the tomb, blonde beard and white dazzling feet. And a strange thought arrived to Feliz, abrupt for the situation: God was real, and there would be a new resurrection. All things would pass away and reappear again, and he would have the pleasure of pursuing them again, for eternities to arrive. He said nothing, and Duermo continued to speak.

“This will be our final case. One out of many we have never solved, and will never solve. And you, my brother, you must accept it as I do. Like a dead starling. You and I will hold clues that will lead to nothing. Stars upon our body, with no savior to point to. And that is the purpose of our lives. I am convinced.” He motioned to Roberto with his lips and sat down on the empty chair before Feliz. Roberto proceeded to tie him down and blind him. Feliz was blinded soon after.

“No one will be leaving here with any kind of answer. They will find us and be confused. And that is alright. That is the hope. Accepting the ineffable. Defining this new year.”

“What about Ricarda,” whimpered Feliz, “why did she have to die?”

“To confuse you, Feliz, it was always to confuse you. You were born for the confusion.”

In the darkness, he could hear an intimate explosion and a wet feeling on his face. He would be next and he was okay with it. There would be a sudden nothingness to overcome him. And then, with confidence, he knew he’d awaken, and search all over again.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.