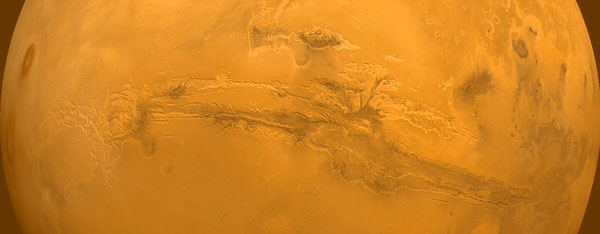

“I’m serious,” Tung coughed, puffs of smoke escaping his lips. “One day, this place is going to be a low-g Earth. Over-population solved for another hundred years.”

“Yeah, a millennium from now. By then we’ll be reproducing so fast that it will solve over-population for about 2 minutes.” Ricky swiped the blunt from Tung’s fingers. “You talk like terraforming is as easy as building a terrarium.”

“My old man doesn’t think it’ll take that long. He thinks within our lifetime.”

Ricky rolled his eyes and took a long pull.

“They already have the big magnet up there!” Tung gestured at the rover’s ceiling. The month before, The Project had made its biggest achievement since first establishing bases on the red planet: the activation of Shield Station, an enormous electromagnet projecting an artificial magnetosphere.

“Think about it, man!” Tung smacked his friend on the arm. “With a magnetosphere, the pressure rises, the temperature rises… before you know it, apartment complexes and big box retail!”

“Imagine what we could do on trampolines.” Ricky giggled.

“That’s the spirit,” Tung smiled, pulling out his pad.

“Please don’t post any of this stupid-ness to The Project’s social media accounts.”

“I wasn’t.” Tung slid his pad back.

“Cheek!” A shrill voice cracked over the radio. “Cheek! Get that rover back to Beta.”

“She sounds pretty mad.” Ricky waved smoke away from the communications console.

“She always sounds mad,” Tung said. Ricky giggled some more. After a moment, they stopped laughing and while Ricky took another drag, Tung looked side-long at the comm console. “Maybe you should answer her.”

“Shit!” Ricky thrust the joint at his partner and fumbled over the controls. “Cheek here.”

The instant Ricky let his finger off the transmit button a string of verbal abuse so violent emerged from the rover’s speakers, Tung figured Ricky’s mother felt it back on Earth.

“We are back on route to Basecamp Beta,” Ricky reported.

“Have you not been listening!?” Commander Daniels screeched. “You should have been back two hours ago!”

“Right. Roger.” Ricky replied.

There was a long pause while Tung took another drag and fiddled around on his pad.

“Guess she’s satis-“ Ricky began.

Her voice returned, measured, slow, struggling to maintain a tempered tone.

“Then where... exactly... have you BEEN?!”

Tung reached over and knocked Ricky’s shaking hand away from the comm unit.

“Listen, Tammy,” he said as Ricky winced. “We delivered the supplies to Dr. Minick, but you know that old botanist never shuts up and Cheek here has the backbone of a single-celled organism. That’s why he’s verbally taking it up the ass from you right now, and why he couldn’t pull away from the good doctor yammering his ears off about root formations.”

It was the truth, minus the detail that they had left with some of the good doctor’s latest hybrids. He swore he wasn’t trying to make the stuff stronger. His objective was to make plants of all varieties with better cold resistance and low-pressure tolerance. And yet his weed just kept getting better…

‘Tammy’ finally replied with a terse, “get back here now.”

While Ricky followed the kilometer beacons back to base, Tung triple wrapped the rest of their weed, completely undid his pressure suit just to shove the package in his pants – which had them both snickering so much that Ricky nearly ran them off the rim of the crater he was circumnavigating – then Tung slipped the butt of their joint into the drop shoot and set the air controls to maximum scrub.

“The filter algae is going to be higher than Olympus Mons.” Ricky laughed at his own joke. In truth, the best part about hot boxing a rover was that if you had even a twenty-kilometer drive ahead of you, the biofilter tanks would completely take care of the air before you got to your destination. Add a dose of purifier while you run the fans and you’d come out smelling like a compressed can of pure O2. When they popped the seal on the rover at base camp, Ricky and Tung would fly right out and clean your keyboard.

Ricky was mortified when, instead of reporting straight to Commander Daniels, Tung dragged him all over the base, casually making his usual deliveries.

No one paid Tung. There was no money on Mars. Tung accepted only handshakes, hugs, and smiles from the engineers and scientists he delivered to.

When they finally entered the command center, they found the room bustling with activity. Uniformed aides power-walked from station to station, every console was manned, and all of the senior staff huddled around Commander Daniels.

Tung grabbed a passing ensign by the arm. “What’s going on?”

“Project director landed at Gamma Base two hours ago,” she said. “He’s on his way here next. Surprise inspection.”

Tung turned to Ricky, cowering by the door. “This is perfect. She’s going to be way too busy to spend time yelling at us.”

“Cheek and Chung!” Commander Daniel’s voice boomed over the busy room. She stormed toward them, practically throwing her peons out of her path. “Don’t think I can’t still smell that.”

“I told Ricky to stay by the door.” Tung leaned and whispered: “Poor guy shit himself after that high-quality tongue-lashing you gave him.”

“I don’t care if your daddy is on the board of directors or if your little friend has a Ph.D. from M.I.T,” Daniels seethed. “You’re both a waste of space on this mission and I think it’s time we sent you both home. There happens to be a shuttle here...”

“Yes! I heard the director is coming. Big day for you. I’d love to interview him for the socials.”

“You’ll be too busy to talk to the director.” Commander Daniels straightened, pulling away from Tung. “I have an important job for you.”

“You do?” Tung and Ricky said in unison.

“Mr. Cheek, I believe you are qualified to monitor the ecopoiesis test beds? The ones near old Basecamp Alpha have stopped transmitting data. I’m sending you and your friend Tung out to check on them.”

“Basecamp Alpha is halfway across --” Tung began to protest.

“It just so happens Dr. Minick requested some additional supplies. You can stop back in and chat with him on your way.”

“We were just out there --” Ricky began.

“It’s fine,” Tung interrupted. “We’ll go. Not much for a PR rep to do, but if it’s where you want me…”

“I’m sure you could take some videos of him extracting soil samples for the company Instagram.”

“Damn, you are old.”

* * *

As they departed, Tung saw the director’s motorcade pulling in over the rust-colored hills to the east.

“You’re supposed to be the driver,” Tung grumbled.

“You know Daniels just wants us out of the way for the director’s inspection.” Ricky leaned his chair back and closed his eyes.

“You must be sobering up,” Tung soured. “Your intellectual indignation is returning.”

“Don’t be jealous that I’m both quantifiably and qualitatively smarter than you.”

“I like you better when you’re high.”

“I’d feel insulted if I didn’t generally agree with you.”

“I’m sure it’s a real burden being so smart all the time,” Tung scoffed.

Four hours later, crawling along at 20 KPH, they reached Minick’s facility. Four greenhouses branching from the main habitat tube made it look like a lowercase ‘t’ with an extra cross. Nestled deep in one of Mars’ lowest points, the old botanist had told them all about how this was the best place on the whole planet for growing any Earth plants because of the atmospheric pressure. Ricky later pointed out to Tung, through a cloud of smoke of course, that “that makes absolutely no sense. The old lighter is running low, man,” and here Ricky pointed at his own head. “He works in pressurized greenhouses! Inside.”

Tung tried to point out the strange color of Minick’s valley, how the ground wasn’t the same dull, dusty amber as the rest of Mars, but a dark rich garnet. Ricky wouldn’t hear it. What did it matter? No plants could grow on the surface of Mars.

Ricky and Tung wheeled the good doctor’s supplies through the airlock on hand trucks.

“Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you,” Minick said embracing them both when they were done, throwing his arms wide around the whole bulk of their suits. “I would stop and chat but I’m so anxious to get to work.” His sharp blue eyes, the only thing about his whole person – skin, hair, teeth – not a shade of ashen gray, flicked from them to the supplies.

“What’s the hurry?” Tung asked.

“Haven’t you heard? Haven’t you heard? The director has landed.” Minick’s chalky hands shook with excitement.

Ricky smiled. “Is he coming here?”

“Oh!” The old man threw a finger of inspiration up in the air. “Let me get you something for your trouble! This is exciting. So exciting.” His voice faded as he disappeared around a bulkhead into one of the two greenhouses. They could see straight through from the airlock to the doctor’s lab area and his sleeping corridors beyond that. And from where they stood, straight back to the other side, plants lined the walls in pots.

“I kinda want to ask him about the soil,” Tung whispered. “Did you see it? It’s almost black all around the compound.”

Ricky leaned close and whispered: “It’s called nighttime.”

“Fuck you.”

Minick whipped back around the corner, a tiny sampling bag in one hand.

“Sorry, sorry, sorry, boys. There’s not much this time. Very, very, very, very busy. Lots to do.”

And like that they were shooed back into their rover.

* * *

Basecamp Alpha was a twelve-hour drive to the west, partly through rough terrain, made worse by their late-in-the-day departure. The long, nighttime haul put Ricky in a bad mood as they jostled up and down sand dunes.

Alpha had been abandoned a decade prior when The Project transferred ground command to Beta. But, Ricky explained as he drove, all of Alpha’s science equipment was still functioning and that included the three enormous biodomes that had supplied oxygen to the base.

“Three whole biodomes for a base a fifth the size of Beta and we only have two. Shit was so inefficient back then.” Ricky shook his head, swearing as the rover jostled over some rocks. “Now they’re just overgrown forests filling reserve tanks.”

Tung considered pulling out the botanist’s weed, to turn Ricky’s swears to giggles, but there was so little of it. He leaned his chair back and closed his eyes.

They arrived at Alpha in the early morning. Ricky pulled up right beside the old basecamp so they could recharge the Rover’s zonked batteries. They slept through the morning, woke up to eat lunch and work in the afternoon sun.

Tung with his pad and Ricky with his spade,

departed the rover for a Martian escapade.

Tung posted it, then switched over to video and hit record.

“Well Ensign, tell me about Martian dirt.” He said in his best reporter voice.

“Seriously?”

“Our readers at home want to know everything about their future gardens. What’s the grass going to be like in their Martian lawns, Ensign? Will it be red?”

“Stop calling me ‘ensign.’”

“I apologize, Cadet.”

Ricky sank the shovel into the rusty grit at his feet, seemingly at random.

“Ah yes, the perfect spot,” Tung quipped.

Ricky scooped up a clot, then bent to examine it. Combing his fingers through the soil, he came up with a finger-sized screw with a domed glass tip.

Tung leaned in with his pad to take a picture.

“Just don’t caption it something about litter or flat tires,” Ricky pleaded.

“Tell me what exactly this is and I’ll see if I come up with anything better.”

“It’s the first experiment the Alpha Base crew ran on Mars. There’s hundreds of these in the plain around us. That little dome collects sunlight and inside the screw is algae from Earth growing in Martian regolith.”

“I think I’ll caption it, ‘Martian Hardware.’”

“It’s on Wikipedia. Post a link.”

“You stick to ridding Mars of these rover tire hazards and leave the social media to me.”

Ricky rolled his eyes and went back to working. Tung found a rock to lounge against and snapped a selfie with Ricky digging in the background.

Working hard on Mars! He captioned it.

An hour later, Ricky determined the screws weren’t the problem. An hour after that, he realized the problem was the satellite uplink for this particular field.

“That doesn’t sound like our problem,” Tung said, assuming they’d have to send out a repair crew and that Tammy had managed once again to waste their time.

“It’s just a connection problem between the testbeds and the uplink module. I can fix it.”

Tung watched carefully only because he knew at some point, in all the diagnostics and electrical checklists, that Ricky would have to disconnect the power supply and reboot. When he did, Tung snapped a picture.

Even on Mars: “Have you tried unplugging it and plugging it back in?”

Sure enough, it was working again in ten minutes.

“I think Minick is up to something.” Tung said. “That ground around his compound is so dark.”

“Either he’s not crazy and he’s conducting some kind of experiment on the soil or he is crazy and so are you.”

“So the first one then? Rocco’s Razor, right?”

“Occam’s Razor,” Ricky said slowly, disbelief riding on every syllable.

“I think he’s going to start growing stuff.”

Ricky scoffed.

“Mars has a magnetosphere now,” Tung offered.

“And for a second I thought you understood Occam’s Razor. Are you going to help me pack up these tools?”

Tung made no move to help.

“Have you had any signs of atmospheric pressure building?”

Ricky turned and stared at him. “That’s the first work related question you’ve asked me in the year we’ve been on this planet.”

“You’re right,” Tung said. “I’m finally selling out.”

The sun had set when they piled back into the rover. They weren’t expected back until morning and neither of them were in a hurry to get back under Tammy’s thumb. While Ricky heated dinner, Tung pulled Minick’s weed from his pocket and some rolling paper from where he had it stashed in one of the rover’s fuse boxes.

Some hours later, the weed nearly gone, Tung stared idly at the ceiling.

“So the magnetosphere is like a balloon around the planet, keeping the atmosphere in?”

Ricky, flat on his back between the four rover seats, rolled his head back and forth before finally saying, “sort of.”

“So, with the big magnet shielding us from the sun, all we have to do is fill the balloon up now.” Ricky coughed a plume of pale gray and strained out the words, “I said sort of.”

“C’mon, Ricky. Rickeeee. Don’t you want to do something with that big brain of yours? Aren’t you tired of digging soil samples? Let’s terraform Mars.”

“Oh, right now?”

“Right now!”

Ricky convulsed with laughter. “Why the hell not?”

“That’s the spirit! Now, use that over-sized evil villain cranium of yours to figure out how we can start pumping this planet full of oxygen.”

“Wait, do I have a big head?”

“It’s still too cold and the pressure is too low to just go planting rainforests…”

“My mother always complained about how painful giving birth to me was.” Ricky mumbled, feeling at the shape of his head.

Tung looked out the windshield at the Martian nightscape. Ricky had backed up to Basecamp Alpha, so splayed out before them was a rolling, shadowy plain beneath a field of stars. The only structures visible, the only signs of human colonization, were the three biodomes.

“I’ve got it!”

* * *

Ricky slowly opened the panel on the side of the reserve tanks’ access terminal. At first Tung thought he was being careful, that maybe he was scared, but then Ricky dropped the huge metal door on his foot and started dancing in pain. Tung would have made a gif out of it, but he was laughing too hard and way too high to think about his actual job.

Inside the bulletin-shaped, meter-high terminal, a bouquet of pipes sprang from the buried oxygen tanks sprouting valves like flowers. Ricky pulled the wrench from his belt and started loosening one.

“Just a slow trickle. Give the atmosphere a tickle.” Tung giggled.

Ricky snorted. “The first Martian poet.”

“I have a gift.”

“I thought you wanted to speed this up. Shopping malls and trampolines?”

“You wanted the trampolines.”

“Here we go,” Ricky announced.

It started as a hiss, audible through their heavily insulated suits, and they watched the compressed white gas piss out into the wind.

“So the overgrown forest in those biodomes will continue to produce oxygen and refill --“

Tung didn’t get to finish his half-baked sentence.

The red valve, surrounded by safety warning stickers, rocketed off its container and ricocheted around inside the terminal housing. Ricky toppled backyards in slow motion, landing flat on his back. The compressed O2 gushed out like a fire extinguisher. Ricky let out a string of nonsensical swears. Tung lifted him up by the armpits.

“It’s not meant to be released into anything except a habitat or another tank,” Ricky gasped, gaining his feet. “Both of which have regulators that --“

Ricky stopped mid-sentence as the whine of escaping gas grew in pitch and volume. A new stream, thin and sharp, jutted out from the opening, spewing O2 into the night at a different angle.

“The blown valve nicked another line.”

“Can we shut it off?” Tung asked. “There’s got to be-“

Something else burst. They couldn’t see it, but they heard it and they saw the sparks that caught briefly in a brilliant spout of flames.

Ricky turned and ran.

“We have to turn these off!” Tung shouted unnecessarily into his helmet radio.

“There’s more than just oxygen tanks down there,” Ricky panted back at him. “That might be an ethylene line.”

“Uh what?” Tung asked.

“Run,” Ricky gasped. “Run… idiot!”

“But --”

Tung, watching his friend desert him, didn’t see the fireball erupt behind him. He only heard a violent popping and saw the landscape before him light up as though beneath a fireworks display.

“Coming!” He ran after his friend.

It wasn’t Tammy Daniels’ voice that screeched into their helmets, though Tung prepared himself for that as he huffed and wheezed across the dunes. It was worse: a voice he didn’t recognize, hailing them from the orbital control station. Tung reported a malfunction at the Alpha Biodomes and was thankful they asked no more questions.

Collapsed beside the rover, they watched as the underground tanks exploded. The bullet-shaped terminal became a raging torch. One of the biodomes ignited, lit from within, like a giant orange lightbulb.

If Ricky hadn’t been crying as he watched his future go up in smoke, the M.I.T. grad might have told Tung about the safety measures preventing the other two biodomes from exploding as well. Without this knowledge, it just seemed natural to Tung when the others exploded, their aged safety measures failing. The hyper-oxygenated forest within each dome ignited in turn, the domes bursting from the heat, puffing dark clouds high into the eastern sky.

Hours later, as the sun lurched over the hills, their own private hangover from hell, rovers arrived from Basecamp Beta and emergency shuttles landed from orbit and gliders coasted in from Basecamp Gamma.

Command Daniels said nothing to them. Ricky’s sobbing regrets had gone over an open comm to the orbital station, confession enough of their plans and deeds. They were ushered into a rover and driven back to Beta.

Tung seldom took in the landscape completely sober. It was a world of contradictions: a desert that dwarfed any on Earth, dryer than the Atacama, colder than the South Pole. Cliffs unchanged for millennia stood over dunes reshaped monthly by wind storms. An environment so unwelcoming, so barren, you couldn’t help but feel vulnerable, insignificant and alone and yet it stood as a vastness and openness that made one’s heart swell with the possibility of time and space and heritage of not just Mars but the galaxy itself. This was the grand new frontier.

It totally sucked.

* * *

In the second between the bolts withdrawing from Tung’s door and the door swinging open, Tung resolved to stay laying on his bed as a way to say, “Fuck you, I don’t respect you at all,” to Commander Daniels.

“Don’t get up on my account,” came a deep, accented and very familiar voice.

Tung leapt out of his bunk and lurched across the room at the director.

“It’s all my fault. I got the weed from Minick. It was my idea to siphon oxygen into the atmosphere.”

The director held up a hand. His uniform half undone, he stood no taller than Tung’s modest height, but even aged and balding as he was, the Haitian never failed to be imposing.

“They can’t fire Ricky,” Tung sighed.

“Oh yes, they -- we -- can.”

“Sir, please.”

“’Sir?’ ‘Sir?’ Don’t tell me this ordeal actually has taught you a thing or three, laying on your bunk like the rascal you’ve always been.”

Tung felt his shoulders slouch in defeat.

“Uncle John --“

“That’s more like it.” ‘Uncle John’ or the Director of the Pan-Pacific Cooperative Martian Colonization Project took a seat in the room’s only chair.

“Uncle John, Ricky’s a good kid. I’ve just been a bad influence.”

“I’m sure every word of that is true.”

“Then fire me and not him.”

“That ‘kid’ is also two years older than you, a Ph.D. and a trained science officer.”

“He’s what space explorers are supposed to be like.” Tung slumped back on his bed. “You know: the best of the best. People who earn glory only through selfless acts that advance the whole of humanity. I’m just a rich kid who came out here to get as far away as he could from his rich dad.”

Uncle John cleared his throat and wiggled his gray mustache. “The Project is backed by lots of wealthy, influential people who also happen to have kids.”

“Then why won’t you fire me?”

Uncle John dug his phone out of his pocket. It was a chunky, pewter colored device thicker than his already thick hands, the specialty devices that worked only on Mars, in orbit and anywhere near project operations. He tapped the screen only once and turned it around, showing what he already had queued up on the screen. It was the selfie Tung had taken while lounging on the Martian soil, Ricky, in the background, juggling the auger and soil sample instruments.

“Hundreds of millions of followers keep you from getting fired.”

“They’re company accounts.”

“And you’re doing a fantastic job running them. A better job than any other board member’s kid could do.”

Tung rolled his eyes.

“Hundreds of millions, boy. That wasn’t an exaggeration.”

“I know.”

“This project is not cheap. Its results are very long-term. Your social media presence keeps us in the public’s good graces. As for your friend, well, we have at least one more job for the two of you before he’s shipped back to Earth.”

Tung looked over, confused.

“Minick is demanding that I come see him and that I bring you two along.”

“He has a soft spot for us.”

“Don’t count on it. Apparently, his facility was downwind from your little bonfire.”

“Thus begins the apology tour.”

* * *

A contrite Ricky Cheek kept his eyes on the Martian ‘road’ as they drove in silence. Tung hadn’t yet found the words to apologize to his friend, much less do it in an earnest way, not with “Uncle John” beside him, scrolling through reports on this tablet. Maybe he could say something about being a petulant, impatient rich boy who wasn’t cut out for the slog of terraforming work. But, he didn’t want to give Commander Daniels the satisfaction. She sat beside him, arms crossed, furious that the director had ordered her to come along on this errand, stuffed into a rover with two low-life losers on a four hour trip to see a crackpot botanist. Halfway there, Tung decided it was time for a conversation.

“You know, weed isn’t illegal on Mars.”

The director snorted.

“This isn’t the time,” Daniels intoned.

“We could talk about abortion?” Tung suggested. Ricky stifled a laugh.

“Last time I checked, there was no actual government on the planet and no actual laws. I mean, I’m no expert.”

“We know,” Commander Daniels said.

“Tammy! Good one!” Tung applauded.

The director eyed Tung. “No wonder she hates you.”

“Project regulations forbid officers and associates from being intoxicated while on duty,” Ricky said.

“I’m surprised to hear you’re aware of the regulations,” Commander Daniels fired at Ricky from the back seat.

“That’s enough,” the director said. “They won’t be doing it on the job again. Either of them.”

Tung ignored the ominous nature of those words and pushed forward. “Is that why you never fired us? Couldn’t prove we’d toked-up while on duty?”

“Hardly,” scoffed Daniels.

“She’s tried to have you both fired multiple times,” the director said.

“I’m still not sure why those orders were refused,” Daniels pressed.

“For the good of The Project,” the director said without so much as looking up from his reading.

Daniels tried to compose herself, a failing effort that Tung enjoyed watching a bit too much.

“Half of your basecamp is on Mr. Chung’s supply route.”

“The first Martian drug lords.” Daniels’ voice rang with disgust.

The director, surrendering to the conversation, set his tablet aside. “Tung, were you paid?”

“There was the occasionally returned favor, but --“

“Mr. Cheek?” The director called up to the rover’s front.

“No, sir,” Ricky replied.

“Little wonder I’ve heard from a half dozen scientists directly and quite a few more indirectly how much more bearable these two made their time here on the red planet.”

Commander Daniels was completely tongue-tied and though Tung could think of more than a few ways he’d have liked to tell her to “suck it” in that moment, he knew, contrary to popular belief, when to shut his mouth.

They rode again in silence, until Ricky slammed on the rover’s breaks and Tung hit his head on the back of Ricky’s chair.

“Fuck!”

Tung rubbed his head. The last time Ricky swore, things were about to go boom. “What -- what is that?” The director asked.

Tung leaned forward to look out the windshield.

Though Mars’ signature rust stretched to every horizon, the valley surrounding Minick’s facility was a blanket of seafoam green.

“It looks like… algae maybe?” Ricky suggested. “Or… moss?”

The four of them stared in silence.

“Lichen?” Ricky suggested timidly.

“Just drive us to the facility so we can ask the doctor what’s going on,” Daniels derided.

“You want me to drive on it?!” Ricky exclaimed.

“Of course not,” the director countermanded, pulling his suit helmet from beside his chair and fixing it over his head. The others followed his lead, stepping out of the rover to inspect the verdant oasis.

“How is this possible?” Daniels asked, stooping at the edge of the field and touching the pale green carpet. It really did look like moss, Tung thought, pulling out his pad to take pictures.

Ricky squatted, holding his scanner a few centimeters from the flora.

“Oxygen levels are way up,” he said.

“That’s the point,” came a new voice over their intercom. Tung looked up and saw Minick, picking his way toward them along a path of Martian stones. “That’s the point!”

“Doctor, how is this possible?” The director asked.

“I’d been working at making the land arable, or at least ready to accept some extremophile species I’d been mocking up, but this sudden bloom has to be attributed to these two young men.”

Ricky and Tung looked at each other.

“How exactly --” Daniels began.

“By happy accident of course. Happy accident. Wind carried gas and debris from their fire directly here. Chemical-rich ash settled on top of my fertilized soil as well as a plume of oxygen unspent by the fire.”

Tung snapped a few more pictures.

“This bloom probably won’t last then.” Ricky’s voice fell.

“But still! This is an unprecedented leap forward in my research!” Minick waved his pressure-suited arms. “Unprecedented. Unprecedented.”

“And think of the reaction back on Earth to those pictures he’s taking.” The director pointed at Tung.

“I can’t believe it,” Ricky added. “We’re going to terraform this planet.”

“Someone recently told me that space is supposed to be colonized by the best of the best,” the director turned to Daniels. “I couldn’t disagree more. Just as our species has thrived on Earth, if we are to thrive among the stars, it is going to take all kinds. The rule-followers and the rebels, the methodical and the disorganized, the uniform and the eccentric, the patient and the impatient.”

Daniels’ only reply was a resigned sigh.

Tung and Ricky smiled at each other. Whatever consequences befell them, they’d had a bit of adventure and done a bit of terraforming. Tung picked a panoramic photo to post to every one of The Project’s accounts and captioned it “One planet, two planet, red planet, green planet.”

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.