My name is Simon West. I recently celebrated my seventy-seventh birthday. It wasn't much of a celebration; I've felt like shit all spring. At first I chalked it up to old age, but even the elderly have their good days. I can't remember my last good day.

I finally went to the doctor, mostly to please my son. I've come to the conclusion that Mr. Reaper will be knocking on my door sooner rather than later, but Wallace is still in denial about that possibility. Anyway, Dr. Wood sent me to the hospital for a battery of tests and today I get the results.

I'm not nervous. Really, I'm not. It's not that I'm in a great hurry to leave this world. Both of my parents lived into their nineties and I had hoped to do the same. But I've had a good life – I'm financially comfortable and my son is successful. My wife died nine years ago and I live alone, not even a pet. My affairs are in order, as they say, and no one depends on me. It's as good a time to die as any.

“Mr. West, you can come on back.”

The nurse checks my pulse, blood pressure, respiration rate, and oxygen saturation. It's an absurd exercise under the circumstances, but she's just doing her job and I don't want to ruin her day by mouthing off about it.

“Good morning, Simon. How are you?”

Doctor Wood's voice snaps me out of an ancient memory I'm visiting.

“You tell me, Billy,” I say. Dr. Billy Wood is an old childhood friend of Wallace's. I coached both of them in Little League. Good boys, but neither was much of a ballplayer. That's all right, they're good men. I like to think I had a little something to do with that.

I watched him pretend to study my chart. His shoulders are slumped in a way that reminds me of when he used to return to the bench after striking out in a game. Billy still wears that shame like a second skin.

“It's all right, son,” I said. “I know it's not good. Just tell me.”

“No, it's not good,” Billy said. “None of it. Goddamnit!”

I flinch as he slams the file down, but I'm glad to see my doctor square his shoulders and look me in the eye. None of this is his fault and there's no reason for him to own it.

“Let's cut to the chase,” I said. “How long?”

“Simon...”

“Best guess, Billy. How long?”

“Six months, give or take.”

I'm standing now, but I can't feel my legs. I extend my hand, but Billy ignores it and wraps me in a hug.

“Anything you need, call me day or night. You and Wallace have my home number.”

I stop at the front desk on my way out. The receptionist asks me if I need to schedule another appointment. I shake my head and leave my doctor's office for the last time.

* * *

The old ball field is calling my name as I climb in my car. I've found that the older I get the more time I spend looking into the past. That's especially true now that Billy has confirmed that I have so little future ahead of me.

To my surprise the wooden bleachers are still there and I take a seat. It's the time of year when the air should be crackling with excitement and the sounds of the boys of summer. None of that is happening here, so I'll just have to use my imagination.

I close my eyes and look down the bench at my teammates. We're a motley collection of kids from various neighborhoods and socioeconomic backgrounds. The main things we have in common are our love for baseball and our middling talent for playing the game. Danny Jacobs, our catcher, is the exception. He's our age, but plays older and moves with the God-given grace of a natural athlete.

Second base is my position, mostly because I'm small and don't have a strong arm. Don't get me wrong – I was good enough to progress through Babe Ruth League, Connie Mack, and American Legion ball. I even played in college, but that's where I hit my ceiling. There were no invitations to join elite college players in the Valley League or Cape Cod League over the summer. No major league scouts ever knocked on my door. That's all right; I never expected to go as far as I did.

It's getting warm. I remove my jacket and look back out at the field, now choked with weeds and knee-high grass. The bases are gone and the white-chalked foul lines have disappeared. The town has sold the ball field – my field, my youth – to some developer. The mayor justified the decision based on a lack of use and upkeep costs. I guess kids today are more interested in playing on their computers and phones than getting up a ball game. If there's a silver lining to my medical condition it's that I won't live to see whatever monstrosity arises from the destruction of this ground.

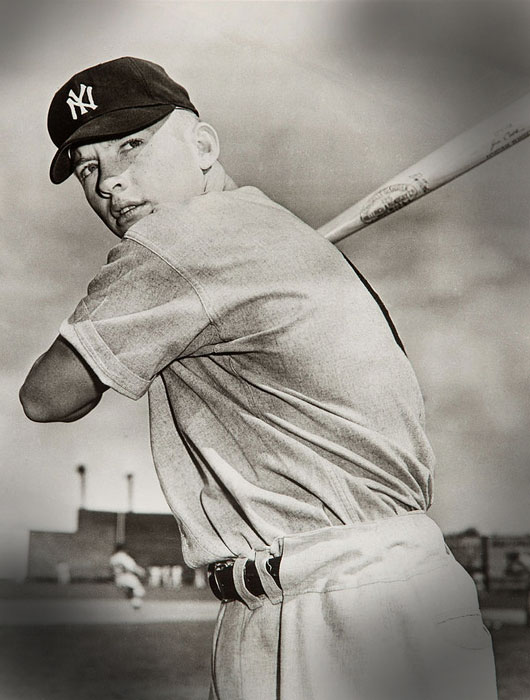

I'm getting too worked up about this, so let me tell you how it really was back then. We all had our favorite players and when we came to bat it was always the bottom of the ninth with the bases loaded in the seventh game of the World Series. Mickey Mantle was my guy. He was the Mr. October before Reggie Jackson came along. Check out his stats if you don't believe me.

Me and Danny Jacobs almost got into it a couple of times, and not because Jacobs was a Yogi Berra guy. When Jacobs came to bat he would usually do Yogi proud with a scalding double in the gap or even a home run. With me as his stand-in, The Mick would usually have to be satisfied with a soft single to the opposite field. Danny never tired of telling me to eat my Wheaties if I wanted to stop swinging the bat like Mantle's girlfriend.

It's starting to rain, but it's a short walk to the parking lot. Would you believe it if I told you I never hit a home run in my life? I know Danny Jacobs would. That's an embarrassing admission for someone who played the game as long as I did. But it's all right, I'm still Mr. October in my mind. I'll take that to my grave.

* * *

Wallace is parked in my driveway waiting. I brace myself and step out of the car.

“Dad, where have you been? Your doctor's appointment was hours ago.”

“I was sitting in the bleachers at the ball field, Wallace. My ball field, the one your mayor and council are getting ready to bulldoze because you sat on your hands and did nothing.”

“That's not fair, Dad. I'm the town manager, but I don't have a vote. You know that.”

“If you're the town manager you can at least light a fire under the director of the parks department and make his people clean up the field. It's a disgrace in its current condition.”

“That would be a pointless exercise and a waste of resources, Dad. You know that.”

I'm suddenly exhausted and ready for a nap. Maybe I'll sleep for the next six months. Good practice for death.

“So, what did Billy say?”

“I'll be dead in six months, and the way this town is going I can hardly fucking wait.”

“What...no, we'll take you to the Mayo Clinic. I'll make some calls when I get home. They'll know what to do.”

“Wallace...”

“You take it easy, Dad. I've got this.”

“Wallace! Just let it go son.”

“Dad, I can't do that. Let me do something for you.”

I'm tired, but something's sparking in my brain. It's a long shot, but I've got nothing to lose, so I tell Wallace what I want.

“Can you make it happen?” I ask. “It's all right if you can't, but don't bullshit me.”

Wallace is trying hard not to cry.

“I can make it happen, Dad,” he said.

* * *

It's a beautiful day for baseball, wispy cirrus clouds floating across a bottomless blue sky. The temperature is in the seventies, warm enough to soothe the persistent ache in my bones.

Wallace has come through big time and I'm so proud I can't get the words out to tell him. Our ranks have been thinned by death and disability, but my son has found all my childhood teammates who are still living and mobile. He recruited players who came through a few years after me to fill out the squad.

I'm wearing an old uniform from my Connie Mack days. It's a good fit now that I've lost so much weight. I had to buy a new glove and bat because they disappeared somewhere along the way.

The field looks better than it ever has. Wallace has even brought in an umpire crew that normally works the high school games. I have a feeling he's paying them out of his own pocket. He's a good son.

Butterflies are dancing in my stomach as I wait for the game to start. The bleachers are packed. I haven't been this excited since I last stepped onto a field nearly sixty years ago. God, I love baseball.

“Play ball,” the umpire yells. My heart leaps into my throat as I jog out to my position. I know I'm moving like the tin man from the Wizard of Oz, but at least no one is laughing.

I'm tired by the third inning, but I'm not about to quit. The score has been going back and forth. At the end of the eighth inning we're tied at six runs apiece. I take my seat on the bench and wait to see if I'll get one more bat in this lifetime. Right now, I would almost trade that chance for a soft bed and a warm blanket. Almost.

Okay, now this is starting to feel like a dream. There are two outs, but somehow we've loaded the bases and it's my turn at bat. I've had a pretty good day, so far. Made some plays in the field and hit a double over the shortstop's head in the fifth inning.

One more chance,Mick. Make it count.

There's a substitution at catcher and, oh shit, it's Danny Jacobs. I stroll up to the plate, wondering if Jacobs will remember this old scarecrow as the boy he used to bedevil all those years ago. I decide to take the initiative.

“What's up, Yogi?” I ask.

Jacobs looks up and I can see his eyes widen.

“Not much, Mick. You ready to roll a candy-ass ground ball to our second baseman?”

“We'll see,” I say.

And just like that I'm hopping mad and ready to beat the shit out of someone. I dig in at the plate and wait for the pitch. Thompson's best pitch is a fastball and he can't walk me with the bases loaded. I'm sitting dead red when the pitch comes in and I turn on it just like The Mick did eighteen times in his World Series career.

Bobby Wilkes is playing a shallow left field because he has a weak arm and knows I don't hit for power. This time he's wrong.

The ball sails over his head and takes one hop against the fence. I'm off like a shot. By the time I reach second I feel like I'm backpacking a load of concrete. Wilkes is just getting to the ball, but he's fumbling it. I feel for him. Bending over when you're deep into your seventies isn't the easiest thing in the world.

The shortstop takes the relay from Wilkes as I round third and ignore the stop sign from the coach. Fuck that. It's either going to be a home run or the last out of the game. The last out of my life.

Unlike Wilkes, the shortstop, Parker, has a cannon for an arm. I know it's going to be close.

I'm ten feet from home plate when I hear the relay whistle past my helmet. I'm already into my head first slide when I feel something in my body break apart.

My fingers are clawing for the edge of the plate as Jacobs takes the throw and slaps it down on my hand. I roll over and look up. I can see the umpire start to raise his hand and stop. He's looking at Jacobs. I see Danny make a slight movement with his head.

The umpire thrusts his arms wide apart, “Safe,” he hollers.

Danny takes off his mask and smiles. “Mr. October,” he says. “Congratulations, Mick.”

Something else inside my body surrenders. I close my eyes. Full stop.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.