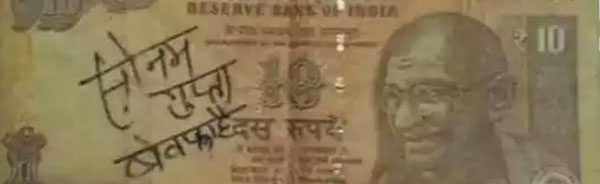

(On November 8, 2016, the Government of India—in an attempt to purge the nation of black money—demonetised old banknotes and announced new bills. Amid speculation and debate by yay- and naysayers as to where this move would lead the country, an old banknote bearing a bold, handwritten inscription—a heart-wrenching accusation by an anonymous, wounded lover—went viral on the internet, and with this began a carnival of memes, anonymous responses to the lover’s charges, and origin stories that kept the nation employed for months in the wildest, and often risqué, conjectures. This is the mother of all origin stories.)

“Arey, chacha! Heard you tossed around in bed all night? Told you it’d happen if you sleep with cash and not your woman!” Chintu took a jibe at Trilochan Shah first thing in the morning.

“You rascal! You got nothing better to do? Look at Sharma ji’s son. Lad’s in Patna for six years now preparing for the Civil Services. And loafers like you? Wasting time and your father’s money!” The neighbourhood grocer fumed, still sour from his bland morning tea.

“Easy there! And what makes you so sure Bajrangi Sharma’s son is chasing letters and not skirts for six years?”

“I do have a damn good idea what you’re up to. Anyway, the grocery list. Hurry! There are long queues at the bank already. Gotta get the new notes today.”

“Yeah, yeah. Bank ain’t running away. What makes you so sore, eh? Wife beat you up again?”

“What did you say? You—”

“Calm down, sir! Here’s your list, have this packed: 10 kg wheat flour, 5 liters full cream milk, 1 kg Govind Bhog rice—the one with the flowery scent, cardamom—10-rupee sachet, 500 grams jaggery powder, 200 grams of all the dry fruits you got—don’t just fill it with dried dates like last time, you know. How much for this saffron sachet? It says 25 rupees here. This stuff’s real, right? Looks like TV antenna wires in posh packaging.”

“You want real saffron? Go get it from your grandfather’s plantation in Kashmir,” Trilochan Shah smirked. “Why full cream milk, scented rice and dry fruits today? Folks coming to see you for their daughter? But who’d be fool enough?”

“I wish, chacha! Such luck eludes me. For now.” Chintu sighed. “My uncle’s visiting. His son has board exams here. Uncle will stay with us for two-three days, the son for a month. He’s Mom’s brother, so it’s kheer on the menu. Would have been the same old dal bhaat chokha if it were Papa’s folks.” Chintu said, grinning. “Anyway, here’s the money.” He handed Mr. Shah a 1000-rupee note.

“Right, right. Hahaha! Wait, there’s something written on this note... ‘Sonam Gupta bewafa hai.’ What the...! Keep it. I’m not taking this. Bank’s not gonna take this either. Gimme another.”

“This is all I got, chacha. Papa took all notes to exchange them at the bank. Put it on our tab then.” Chintu shoved the groceries in the scooter’s dicky and began to tie the 10 kg flour bag on the back seat.

“Alright, but settle it by the weekend. Government’s tightening the noose, you know.”

“Yeah, sure. I’ll see to it. Now don’t make me late or I’m gonna face Mom’s wrath.” Chintu had another look at the note and, kicking the scooter to life, left.

The Prime Minister of India had taken the country by storm the night before when he announced demonetisation on live television, discontinuing Rs. 500 and Rs. 1000 banknotes and issuing new bills in the denomination of Rs. 500 and Rs. 2000. A few days were granted to have the discontinued notes exchanged for new bills. Amid growing apprehension surrounding the new currency rules (news channels were pretty sure the new bills came with pre-installed GPS chips to lead anti-corruption agencies to politicians’ basements), Trilochan Shah rejected the banknote bearing the lover’s lament the same way Sonam Gupta would have trampled upon her suitor’s dreams.

Driving at a demeaning 20 km per hour (thanks to the 10 kg flour bag tied precariously to the back seat), Chintu crossed the bazaar, wishing cinematic heartbreak upon the heartless hourie, his curses echoing the collective lament of generations of scorned lovers.

#

The year was 2000-something when starry-eyed kids from the district, fresh out of school, were flocking to Kota in search of the elixir of IIT-JEE. But the hero of our story was still in Chapra, his hometown. Dr. Rudra Pratap Singh, director of the leading coaching centre in the district, had successfully wooed his latest client with his infallible Don’t be a hopeless romantic running after JEE or you won’t even pass the 12th exams and had had our hero happily enrolled in his institution. It would be proper to state here that had Dr. Singh not played his finest card—What caste are you? I see. You’re my caste-mate, buddy! If not you, then who will crack JEE?—our hero would very well be on the evening train to Kota. Dr. Singh’s caste-mate and our hero, Akhand Babu, began his senior secondary school studies with a newfound I’m gonna hit JEE out of the park swagger.

Days passed without incident when one day Akhand Babu happened to arrive at the coaching centre well before time. Sonam Gupta, considered the most beautiful girl in the Bhojpuri-speaking belt of North India, too, was early and therefore, was sitting on the first bench. As fate willed it, Cupid’s arrow and Puzo’s thunderbolt struck our hero’s chest dead centre, albeit a little to the left (for the sake of anatomical accuracy). One, two, three... By the fourth second it was writ in stone that Ms. Gupta was to be the torchbearer of our hero’s household. Weak in the knees, Babu saheb managed a sheepish grin.

“Huh! Pervert!” Sonam Gupta murmured indifferently at her wide-mouthed admirer, guarding her well-established, hard-to-catch status, and turned to look the other way.

Now, it was a matter of our hero’s pride. (Although he had misheard “pervert” as “parvat”—Hindi for “mountain”—and mistook it as a jibe at his hereditary built, for he was nicknamed “The Bull” by his friends who mocked him over his physique.) The insult, hurled in the colonisers’ language and misconstrued in his native tongue, had made it Akhand Babu’s life’s purpose to tame the English-speaking shrew and bring her home.

Plans were put into motion and from that day onwards a fleet of black Bajaj Pulsar 220 cc motorcycles could be seen performing gravity-defying stunts every evening in the street where Sonam Gupta lived. How long can she ignore my charm?

The face that launched a dozen motorcycles did appear a few times between the curtain and the flower pot on the window sill of the Gupta household, furnishing split-second smiles before vanishing altogether. There was no stopping our hero now.

Board exams were peeking on the horizon when Valentine’s Day arrived, bearing sunny prospects for our lover boy. (Luckily for our hero, February 14 didn’t fall on a Sunday that year.)

Akhand Babu had arrived at the coaching centre an hour before the first lecture, his backpack stuffed with a glass-enclosed showpiece of a man and woman clad in Christian wedding attire dancing amidst battery-operated lights and cotton snowfall in front of a miniature Taj Mahal, a Dairy Milk Silk family pack, and a handmade greeting card with exotic flowers and verse inked in seven colours.

All details had been discussed beforehand. Sonam Gupta should be arriving any minute now. She entered wearing a bright red, embroidered salwar kameez, reminding Akhand Babu of the Pakistani beauties he blamed Jinnah, Gandhi, Nehru and Mountbatten for depriving him of. He started imagining his mother and aunts singing wedding songs at the mandap.

Hello, you there? brought him back to earth.

“Oh. Hi. Happy Valentine’s Day,” he said, and handed over a black poly bag to the girl of his dreams. Ms. Gupta peeked inside, then glancing at the doorway, quickly tore open the chocolate bar from its wrapper. “Have some na,” she said, offering Akhand Babu a bite.

A beautiful girl asking him to split a chocolate with her, that too worth a hundred rupees—it was a day of many firsts for our hero.

“Thanks, but our classmates should be here any moment now,” Akhand Babu said and went to sit on the sixth bench, the generous piece of silky, smooth milk chocolate slowly melting on and staining his gutkha-accustomed tongue.

Daydreams of a destination wedding in Bali and honeymoon in Mauritius occupied the better part of the day. And then came the next morning.

“I’m gonna make her say the magic words today,” Akhand Babu vowed to himself as he entered the classroom.

Director Rudra Pratap Singh was on the dais, biding his time with a wet Relaxo slipper and a foot-long, wooden ruler. The next act of the play, straight out of Webster and Marlowe, began as soon as our hero took the stage.

It ran for fifteen minutes—the longest-running, independent act in the history of A-to-Z Tutorials, Chapra. Caressing his broke back mountain, Akhand Babu carried himself with an unconvincing It ain’t that bad huh gait and sank into the sixth bench.

“Why did he beat the shit out of me? Is he mental or what?” he asked Birendar Rai’s son, Anupam, who sat next to him. Anupam told him how earlier that morning a compounder from Dr. S.K. Jain’s clinic next door had delivered a package to the Director, saying, “Rudra Pratap sir, someone threw this polythene bag in Dr. Jain’s garden yesterday.”

That evening Akhand Babu and his motorcycle mates got their petrol tanks full and rode away from the bustle of town towards the lake on the outskirts in search of answers to their existential crises and the meaning of life.

Inside the dustbin in a corner of Class 12A in A-to-Z Tutorials lay a torn greeting card atop the fractured lover boy in the broken glass showpiece, the card professing: “Roses are red, violets are blue. My heart beats for none but you.”

Mrityunjay Yadav, Akhand Babu’s friend and sole heir to Yadav Petrol Pump, brought his shiny, white Mahindra Scorpio to a screeching halt outside the liquor store that night, the car speakers blaring Kumar Sanu and Altaf Raja tearjerkers at full blast. Seated in the driver’s seat as the boys consoled their martyred friend in the back, Mrityunjay handed a 1000-rupee note to the shop-boy, grabbing a bottle of chilled Old Monk and six packets of Haldiram’s Bhujia. The banknote issued a warning in public interest: “Sonam Gupta bewafa hai.”

#

NOTES:

Arey, chacha! - Hindi for “Hey, uncle!” Elders are addressed as “chacha” (“uncle”) in North India.

Kheer - A rice and milk-based dessert.

Dal bhaat chokha - lentils, rice and mashed potatoes, is a staple, comfort meal in parts of North and East India.

Sonam Gupta bewafa hai - Hindi/Urdu for “Sonam Gupta is a cheater.”

Kota - a city in Rajasthan, India’s biggest hub of coaching centres offering preparatory courses

IIT-JEE - the toughest engineering entrance examination in India.

Salwar kameez - a traditional women’s attire in parts of the Indian subcontinent.

Mandap - a porch or platform set up for Hindu weddings.

Gutkha - a coarse mixture of chewing tobacco, betel nut and palm nut placed in the mouth, usually between the gum and cheek.

Originally appeared in Loft Books.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.