Illiteracy is a curable ill. Aser encounters a town in which the malady is preferred to the consequences of the cure.

Industry in the village of Swale is goat. Goat milk, goat cheese, goat hides, ground goat horns, goat, goat, goat. No newspapers, no market (they all trudge farther up the mountain to Crosspasses for everything from flour to soap), no tavern, and no shaman.

They have no shaman because they are stingy as well as boring. I ought to have kept on walking even after the rain started, because one lousy meal a day and sleeping on a wooden front porch is their idea of adequate payment for services. But there were some ailments among them I could alleviate, so I stayed for a couple days. During a break in the rain, I wandered over the hillsides and gathered up some handy herbs for drying and some for eating, since a bowl of boiled grain and scalded goat milk as a main course doesn't go very far.

I asked the owner of my porch, a floppy gray woman named Cabrilla, if she had any string so I could hang the herbs to dry. "String! String is expensive! For weeds? There in't anything that's going to dry in this weather! Haw!"

"They will if we hang them up over your hearth. When they're dry I'll be able to make enough medicine to cure some fevers and ills for your village for a year."

"A year's a long way off and I don't want no weeds nor magics inside my house," the fool said and went inside and shut her door. A low rumble of thunder and the plopping sound of big drops signaled another bout of rain. I put my cup out in the rain to collect some water, and started to pick out the hem of my cloak, unraveling yarn to braid my own damn string. Between showers, people came to the porch with splinters to be pulled and sore eyes to be cleansed. While it rained, I re-read for the hundred and fifty millionth time White's The Once and Future King. Cabrilla came out wiping her hands on her dirty skirt, eyed the herbs hanging from a stick in the rafters, and glared at my book. "That your book of spells to magic them weeds?"

"No, this is just a novel. A story," I continued when she looked puzzled.

"Oh, that. We used to have books, some of us, but we used them for kindling in the winters. They caught fire fast like they was made for that, and more good they did us than takin' up precious space. Nobody left here in Swale who knows what bewitchment was in 'em."

Burned all the village's books? "You mean none of you can read or write?"

Cabrilla's laughter showed her remaining couple teeth. "We don't need books and magics to trade goats. We can count money and tell if coin is silver or gold."

"But if you know how to read, every book shows you something new. About other people, about the world, what the names of the stars are, that's what makes reading important. Your people could learn herblore, or someone could teach the children how to read so you don't lose the knowledge again. You wouldn't have to rely on passers-by for healing, or the news. Cabrilla, even just a couple people knowing how to read and write could earn a living as scribes -- your village would have other income than just goats."

"Aw, no, we don't want that. Long time ago we got tired of those books puttin' ideas into the young folks' heads -- they'd start reading about the other side of the mountain or about elves and kings and next thing you'd know, off they'd be sneakin', like a spell to give them wandering fits. Now they stay and take care of the goats like we needs them." She heaved herself off the bench by the door. "Bread'll be done rising. And here comes that Pip Hiderson, I'll bet he's here to brag again about his great-granddaddy, that old miser. I got better things to do. Read him one of your spells out of that book so's Pip can't talk so much."

You know, it's one thing to be stupid on your own, but to enforce a standard of stupidity on others is downright criminal. What a combination of traits: stingy, stupid, and stinking of goats. Swale was a real loser of a community.

The maligned Pip approached the porch through the drizzle. "Shaman, can you talk to ghosts? Dead people?"

"Sometimes, if they have something to say or want to be seen. I don't make a habit of pestering them."

"Reason I ask," Pip said, tugging at his wet hat, "is my great-granddaddy Clap Hiderson -- you heard of him? -- was going to build hisself a big house but he died before he could, on account of a lion runnin' him and his goats off a cliff. He had a big treasure chest full of gold and jewelry that he was going to use to get stonemasons in, but he kept it buried so the wife wouldn't spend it on fripperies, and didn't tell no one where. Want you to ask 'im where," Pip finished in a whisper.

"Ten gold pieces," I told him, already trying to think where Granddaddy Clap would be hanging around, if he was at all. Would he haunt a gravesite? The cliff where he died? What would have made the biggest impression on him in his life? The treasure itself, if there even was one?

"Ten!" exclaimed the outraged Pip. "To talk to a ghost? They tell you shamans are always talking to ghosts, how about one gold piece if we find out where the treasure is."

"One gold piece, and twenty percent of the value of the treasure."

"Twenty persons in the treasure?" he asked, sputtering in confusion, indicating they not only couldn't read, they didn't have many math skills, either.

"Forget it. One gold piece in advance. Then show me where he wanted to build his castle." The rain had stopped, still early enough to get on the road, and maybe I'd find a hollow tree or even a hedge to sit under. Get this job done, and get gone. "And get me some kindling and a couple small pieces of dry wood."

We splashed and slid on the muddy path winding around the side of the mountain until we came to a nice flat place on the south side with a gorgeous vista of pastures and crags and a waterfall that cascaded on down the cliffs to the river far below. Old Clap picked a fine piece of real estate. I suspected that since he put saving for this house above everything else, I'd find him still sulking here. I stuck my staff into the ground for him to see -- if he was interested. The kindling and the sticks I took from Pip made a nice little fire, warming my cold hands and feet. I added some of the wilted oregano and basil I'd gathered that morning. "Better stand back", I said to Pip. "Smell that?" He nodded, wrinkling his nose. "Magic," I told him, and waited until he was about twenty feet away before I turned to the wispy outline of the ghost. "Your descendant Pip here wants to know where the treasure is."

There were faint bell sounds, and I saw he had a bunch of ghost goats milling around his ghostly legs. "Is he going to build my house, Shaman?"

"How would I know, Clap? I'm just a hedge shaman, not a fortune teller. Decide: are you going to tell him or not?" I reached for my staff as if to take it and leave.

"Ow-oohhh!" he moaned. "I want my howwwwssse! Tell him! TELL him!"

"He wants his house built, Pip," I relayed.

"Tell him I'll build his house, I don't care! What about the gold?" Pip was rubbing his hands together like a happy housefly.

"Pip says he'll build your house," I said, kicking mud over the little embers of the dying fire. Sure he would.

"In a cave, in a jar, with a map, not too far ..." Ol' Granddaddy Clap chanted. Inside every bored ghost is a bad poet, I swear. I recited the rhyme to Pip, who repeated it over and over. Pulling my staff out of the ground, I headed back to collect my herbs.

I was slinging the bunches over my shoulder when Pip came bounding up, waving a handful of papers, shouting. "Wait! You gotta talk to him again and make him tell me where it is! This map don't make sense!"

"Sorry, I'm leaving. Maybe next time I'm here in the neighborhood. I have an urgent appointment up at the Crosspasses Market at seven, see ya around the campus, have a nice life." Cabrilla was already out with a broom to sweep away the stray bits of goldenseal and parsley.

"Uh-oh," she said suspiciously, "more of them book pages?"

"Twas supposed to be a map, but it's all words and lines," he complained. "Look at this!"

After a quick glance, the woman turned her head as if he had showed her a picture of an orc in a thong. "Get your shaman here to conjure it. She knows how to read spells."

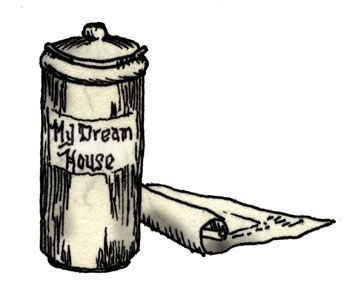

Pip spread four crumbly pieces of paper on the porch, scaring Cabrilla back into her house. The "map" was a blueprint for Granddaddy Clap's dream house on three pages, and the fourth was his last will and testament for the distribution of all his goods, with a note concerning the amount and location of his fortune.

I squinted at the layout of the upstairs floor, turned it sideways. "This is going to be hard to read, Pip. My fee is 20 gold pieces up front."

"What? I got no twenty pieces!" he bellowed.

"Borrow from your neighbors, and then share the treasure with them."

"NO! Clap Hiderson was MY great-granddaddy and I ain't sharing nothing!" His face was darkening with anger, eyes slitted, and he put his hand on his belt knife. "Why do you want so much gold for parsing out a map?"

"It's in Elvish," I told him bald-facedly, eyes wide with what was left of my memory of innocence. I'd have to pay an elf to interpret for me."

"Haw, haw, you're pretty stupid, Shaman, and you just lost a job. Now I know it's Elf writing, next time an elf comes by for cheese, I'll have 'em read it to me! Haw, haw, haw!" Pip gathered up his pages, and left. I stepped off the porch, and Cabrilla came out with a pot of steaming water to scald the wood where the pages and my herbs had lain.

I walked along the muddy track to the main road, and turned right toward Crosspasses, where two mountain roads intersect. With one side trip: at a brick catch-basin for a wet weather spring, I stepped into the brush, following the sound of water gurgling under the stones to the hillside. Laurel bushes concealed the mouth of a small cave partially closed by rocks, rainwater still trickling between them. I moved rocks neatly, humming the rhyme Clap's ghost had moaned, the full text of which had been written at the end of his will.

In a cave

In a jar

With a map

Not too far

From a roadside spring

Water wandering

From a cave

With a jar

And a map,

Not too far

These five hundred get

All my stonework set.

Not too bad poetry after all. A tall ceramic crock stood inside the little cave, sealed with beeswax. I popped the seal with my knife, and took out a copy of the blueprint Pip had waved at me. I used my knife to cut two large squares from my cloak, and emptied glittering, ringing coins into them, tied them up, resettled the lid of the crock, put it back in the cave, replaced the stones, and grunting with the weight of the makeshift sacks beneath my bundles of herbs, went on my merry way to Crosspasses.

And that's what you get for not learning to read.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.