Bataan

I patrol the wards in my wheelchair, a four-star general inspecting the troops: Hey Finley, you pathetic excuse for a cripple, a goddamn stroke is a piss-poor reason to stay in bed for twenty years. Now get the lead out! Listen up, Nurse Thompson, they need a crap-pan down on bed 34, the place stinks like a hell-hole. Let's get this hotel squared away. I especially can't stand shit smell -- I don't think I need to explain. Here, none of the FOBs use the latrine. A couple can hoist themselves up on bedpans when they need to shit, the rest are the diaper generation. Three times a day the diaper platoon comes through -- two teams of two orderlies on each side of the ward, followed by the catheter man. They race each other -- rolling patients, wiping, washing and powdering asses, changing sheets and pillow cases, checking for bedsores, pinning on new diapers. Each team has eighteen patients, the record is one hour twenty-seven minutes from one end of the ward to the other. The losers have the honor of washing down D-Cube; the winners get a ten minute leave to toke a Pall Mall.

Larkin Wray

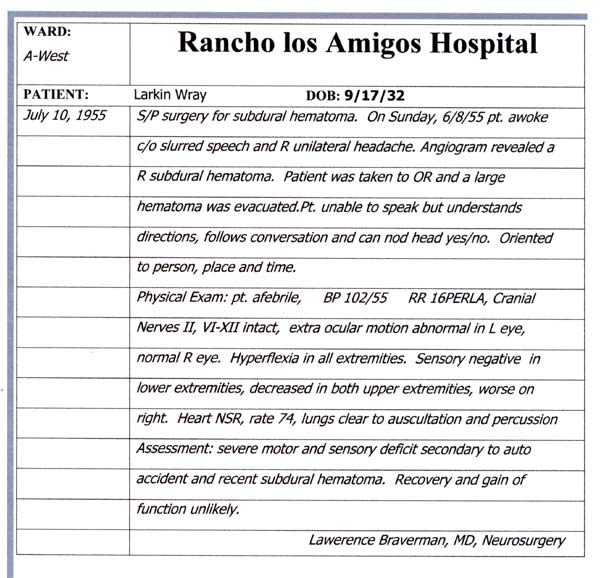

Decline. Neurosurgeon says to the wife my Mara on the other side of the curtain he's in decline. Reclinedeclinesupine. Brainman goes on this sometimes happens with a subdural hematoma. Sub-dur-al-hem-a-tom-a. It rolls off his tongue, iambic, Shakespearian: Wherefore art thou, subdural hematoma? It starts oozing -- at first a headache or some other subtle sign -- and by the time we figure out he's oozing the damage is done. Alas, the ooze hath overtaken me and blown mine neural tube. So no I have to be honest with you we don't expect he'll ever use his legs or arms again. O Mara! O no! Or talk. Oh, yes, he can still hear quite well. Cyclops

I started acting crazy, pissed to the gills and nowhere to go. Once I went to a Halloween party over at my buddy Teke's -- we used to cruise Route 1 on up to Santa Barbara. I dressed up like Godzilla, then pulled my mask off at midnight. Teke says hey my man, no offense, but could you put on your mask, you're really scaring the shit out of the partiers. Hey fuck your partiers, Halloween's my night to shine. Once I went two weeks without washing, then rode my bike through the White Genie Car Wash, a wax job and a shower. The guy at the pay booth freaked when I came out the other end, pipes rapping. It's cool, buddy, you don't have to pay. Once this kinky guy in MacArthur Park asked if he could put his cock in my eye-hole. I winked at him with my good eye: Sure buddy, but I warn you -- there's teeth inside there. And then you die.

The rage was eating me from the inside out, like a bunch of maggots. One night I got wacked on Gallo, jumped on my Machine and headed for Alhambra, hell-bent for revenge. Sure enough, Numero Uno and his Cub Scouts were getting juiced at the A&W. Standing in the middle of the parking lot without his crowbar. Payback time! screamed the maggots. A thousand cc's of super-pissed Harley in second gear chased him down. Just as I was about to split him in two I slid on an oil slick, a ninety degree turn, and slammed into the cinder block wall at the back of the lot. Head first.

I survived, you might say. My Harley didn't.

The saddle and the pegs are the only thing I got left from my Sporty. I put them on my customized Everest & Jennings Traveler XP Heavy Duty Wheelchair. She's fully loaded: a 24 X 17 inch extra deep saddle, deep blue embossed upholstery with double padding, 24 X 1 inch molded wheels with integrated hand rims, double crossbars, 5/8 inch heavy duty solid axles. Made for the highway. Oh, yeah, I forgot the mirror -- I got one of the guys in the shop to make an extender and attach my Harley mirror to my E & J. So I can eyeball who's coming up on me. Don't want no smart ass wheeler passing me here in the hall. Given that the only other guy with wheels in the vicinity is Bataan that ain't likely, motoring around with his one arm. Like my thousand cc's going up against a one cylinder Briggs and Stratton lawnmower engine.

One more touch that I didn't have on my Harley: Old Glory flying off a plastic pole sticking up behind my chair. It lets the orderlies and nurses and guests know I'm coming, so's they don't step out in front of me and get run over. The flag's the reason Bataan and I started getting down. He figured even as ugly as I am I couldn't be that bad, me flying the flag he'd gone down for and all. The crazy fucker salutes the flag every time we pass each other. Yes, Sir!

D-Cube

The modeling thing got me into art. Or at least into hanging around with fashion designers who talked like they were artists. So I took some courses at Long Beach State. Figure drawing, art history, painting. Liked it. Learned something about looking at the world, that there was more to beauty than tan blonds. Talent? One teacher was encouraging, said I had an eye. But that's their job. Never got to find out.

Now the ceiling's my canvas. I watch the patterns: the lines, the stains. How the shadows change as the sun comes in on the east side of the ward and goes down behind the west windows. Like Monet's Cathedral in Rouen. Mostly the patterns are abstracts, line and shading on a dirty white background. Like Mondrian in three-tone. Yeah, Mondrian. I find things in the ceiling. Like when I was a kid lying on my back looking up at the clouds. You name it -- I've found a rabbit, a snake, a hawk looking over its shoulder, the paw of a wolf, teeth of an old woman, cliffs in a mist like in a Chinese painting, balls of a bull, a carrot, an empty cross. An eye with a needle sticking out of it, a four-toed foot, a pistol. Over the years the ceiling has hatched some new cracks and stains. Gives me new things to find. Every day I keep looking.

Bataan

I was no soldier-boy when I enlisted. Thirty six. The brass needed munitions experts who knew how to blow the Japs out of the caves in the Philippines. I was working the copper mines in Arizona, graduate of the Colorado School of Mines. Dropping dynamite down seams was my business, had the knack for exploiting the fissures. I collapsed a few caves in Bataan before the tide turned. Seventy thousand grunts surrendered to the slants. Twenty three thousand lived to tell about it.

It's not like everybody wants to hear about it, the greatest surrender of American troops in history. How do you describe the camps to someone who hasn't been there? Like describing sex to a virgin. The words don't sink in. But they take you back fast, wake you up in the middle of the night.

One of the nurses is Filipino. I threw a couple of Tagalog words at her, something I picked up over there. You have been to my country? she asks. Yes. When was the last time? June, '42. She does the historical math. Hard time? she asks. I move my left stump imperceptibly, like at an auction. She nods, like the auctioneer.

It's tricky riding a wheelchair with one arm. In my case, my right. The tendency is to go around in circles, no way to make tracks without some adjustments. So you have to set up this rhythm with your opposite foot, creating just the right amount of drag on the floor to counter the circular force of the pushing arm. Takes a while to get it: too much drag and you get arm fatigue; too little drag and you veer to the left. When you pick up some speed, there's a slapping sound your foot makes. Then you know you're on a roll, cruising. I always wear out my left slipper and right glove.

I got this phantom arm thing, just at the knuckle of my elbow, where they dismembered me in the camp. I can stand the pain, especially because I have this stuff my Marine buddy Tony Arbutus brings me from the outside. Tony comes every couple months and slips it to me while we play chess out in the courtyard. I've got enough stashed to send a whole brigade to heaven. Usually the arm wakes me up at night, me in a sweat back in Japan. I can't remember what was worse, the pain of the gangrene or the knife. I wipe the sweat down, chug a 'lude, and head down the hall looking for my buddy Cyclops. I know he's out there on duty, minding the troops. We're the SAW Brigade, holding the perimeter, checking on morale. All quiet on the western ward.

Something I'll never tell that Filipino nurse about my Bronze Star. For bravery. For maintaining morale under duress. Sounds like a goddamn cheerleader. How's this for a Bronze Star? -- for three days you're lying next to this nineteen- year-old kid who had his face split open and neck slit as a reward for trying to escape. He gurgles over and over please end my misery I can't stand this pain, just smother me. You know he's going to buy the farm, no way he's going to make it out, all you have to do is hold a shirt over his face for two minutes. Two minutes. You show no mercy, and listen for three more days as he cries and gasps. You wish he'd finally croak goddamn it and give you some peace and quite. On his own, he obliges you. Lights out. Sayonara.

I'd like to think if I had it to do over again I'd have the guts to put the poor kid down.

El Conquistador

When I first came to the Rancho I still had my boxer pecs and 'ceps. And my sexy Newyorican accent. Hey, mamita, come talk to me, I'm lonely mi corazón. How about un abrazo for your boxer-man? That's it, a nice little hug. Oh, yeah, gracias. Late one night, this cute nurse's aide, maybe's nineteen, she's doing her bed checks. Breathing, temperature, bed rails, covers -- usual shit. She pulls the curtains around my bed. I can't really see her good in the dark, just a shadow and a rustle. I tell her about when I was boxin', when I was on top of the world. Nobody here can imagine me strutting my stuff, a contender for the welterweight crown. 146 pounds of pure fury, man, el fucking pollo loco. Ladies and gentleman, from the Bronx, El Con-quis-ta-dor! People wanted to hang with me because I was somebody, or about to be. Women ... like I had to fight them off, Hey guapo, you're sure fine looking, buy me a drink. Hey papi, walk me home. Sí mamita, ¿por qué no? Had to set me some limits to save my bodily fluids, store up my energy. No sex for three weeks before a bout. Oye! Pobrecitas! That drove them crazy. But after I won, they'd line up and I'd be damn sure they were happy. Ay papi, más oh please give me some more, tu eres mi Conquistador! Now the only people lining up are the orderlies and nurses, scrambling to tie me down.

So this nurse's aide lowers the bed rail and pulls back the sheet. I'm tied down on account of my bad behavior earlier that night. I can feel her just looking. My boner gets hard and reaches up to her, like she's a snake charmer. She goes down on me and in the baddest way I just want to stroke the back of her head, ay mi amorcita.

Larkin

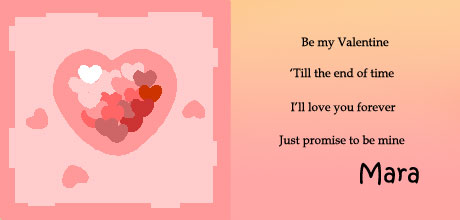

Be mine. Two years off the mountain beneath the ceiling our anniversary coming up. At first Mara comes every day, then twice a week, then twice a month, I know she's out there somewhere no where to be seen since New Year's two months now. I hear her coming down the hall three inch heels tapping. I know her walk like I know her voice: left foot hitting the ground a little harder, not quite a limp, no one would notice it but me. Pulls the curtain around the bed, pulls up a chair. Says she's been traveling, family in Iowa (Family in Iowa? Are you sure? I need a word for them in my encyclopedia: Corn. The Corn family.) I'm so so sorry that I didn't write, I feel terrible, really, work at Bullocks has been hectic like you can't believe, everyone is buying lingerie I won't let it happen again. Mara Mara my lingerie queen most beautiful girl I ever seen please please don't treat me mean. She hands me the valentine then remembers (oops, sorry about that) let me open it for you holds the valentine in front of my face one of those hospital card-shop specials pink and white.

Mara opens a chocolate box and prods the candy scouting for one that isn't too hard. Unwraps one, cream-filled, open wide now and tucks it in my mouth. I want to lick her finger; but no she wipes it on a Kleenex. Valentine red nail polish. Chew and drool. Chew and drool. She wipes the slime with another Kleenex. There, she touched me.

It's a long drive, I better get north of the Pasadena Freeway before the ballgame gets out, since the Dodgers came to LA the whole City's crazy to see them. I nod. (What can I say with a nod? -- I'm awake, I hear you, Yes, No. No way to nod please touch me, no really touch me; or don't go; or my foot itches; or where will I be in twenty years? or does my breath stink? or where will you be?) She turns. Her Bullocks fine knit soft valentine red sweater sways, now she's at the door at the end of the ward this is where she always turns back to wave.

She keeps on walking.

Cyclops

Some volunteer brought me a 'lectric shaver. He didn't say anything, but I could tell my scraggly beard made him nervous. Like something might crawl out of all that hair and jump his ass. Maybe there's a fucking scorpion hiding in there, the kind that can leap eight feet before you know what hit you. Maybe a switchblade too. Somehow I couldn't see myself being clean shaven, next thing they'll be bringing me a tie to wear. But I did put that trusty Remington to good use. Three times a week I make my rounds, Get your shave here, best in town, step right up. I got five steady customers: Larkin Wray, D-Cube, Andrews -- the new kid on the block --, Peters, Salinski. I can always tell how they're feeling today by whether they want a shave. If you're thinking things are all right, I can get through this day, you want to look sharp, spruce up. When you're bottomed out, last thing you want is anyone touching your face, telling you you're looking good. You feel like shit, you want to look like shit.

I been thinkin': maybe I should wear a mask, one of those black jobs that covers your eyes, like the Lone Ranger. Maybe trim my beard, shave my head, get rid of those cigarette stains. Might make me sexy and mysterious, a goddamn hero. Who is that masked man? Maybe not. I like scaring people, the way they step back, give me room. It's the only power I got. Anyways, even the Lone Ranger takes off his mask when he goes home and looks in the mirror.

Did you ever notice how there ain't no mirrors in this shithole?

Blue-J

I done some homework on our man Hernandez. Mr. Contender, my ass. The best he done? A warm-up card over Southgate Arena. A few four-rounders, get the audience drooling before the main event. Twelve minutes, if he lucky. One time on the night shift I wake him up. Hernandez, you full of shit, you were smaller than small time, you the fuckin' warm-up for the small timers. Yeah, you fucking nigger, he say, but I knocked out someone once, yeah more than once. Back in New York before I got the wobblies. You ever knock anybody out? Got me there. The next day I changing his catheter and hold it up so he can see it real good. You sheep-jamming little spic, you know I can make things miserable for you. You may hate my ass, Jailbird, he snarl, but I know you. No way man. So don't even pretend you got what it takes to fuck me over with your catheter tricks.

The other day Hernandez just wagging away on another young thing, this big-titty big-eye candy-striper, 'bout how he done been a contender. She hanging on his every word. Hey, Blue-J, you got a pen, man, this fine young girl would like my autograph to show her amigas. I hand him my pen.

Keep it, man.

Larkin

In Time. Nine months after Mara left off the Valentine's card, time stops waiting. Our third anniversary -- why do I keep track of time in a world where it doesn't matter any more? Time is nothing, it is everything, it is my enemy. Daytime is slow motion no motion nowhere to go. Time is twice as slow in the dark. The middle of the night, awake, staring at the ceiling I can't see, my right hand a mind of its own reaches over searching and finds the wedding ring on my left. Spins the ring, I've lost weight, it glides over my bony knuckle. Unshackled. (Hernandez yelled over to me one day hey Larkin man forget that puta you know in Espanish Esposa don't just mean wife, it means handcuffs too. My esposa forever.) Is this a dream? Is this what I want as if I had a choice? Right hand falls through the side rails, opens. Ping, the ring hits the floor, rolls down the hall, wobbles to a stop. In the dark it sounds like a man-hole cover, when I was twelve we pulled them up and spun them driving the neighbors crazy. Or a departing soul. About ten seconds later the squeaky rubber-on-waxed-linoleum sound of a wheel chair, Bataan on his nightly rounds, rolls up beside my bars taps my shoulder opens his fist. A shadow, really. Hey Lark, I think you dropped something, give me your hand. I nod no. It's yours, right? Let me put it back on. No again no. You sure? I stare up at the ceiling. I know, man. More than the nurses, or Blue-J, or Hernandez, even Mara, Bataan knows. He pulls the drawer on my bed stand, drops the ring in, closes it. In time, kid. He pats my right foot and wheels down the hallway. The ceiling is dark.

In time.

Bataan

I've seen that look in Larkin's eyes before, at least a hundred times in the camps. You learn to read it. Check their eyes and they're clear, looking outward. Yeah, soldier, I see you, everything's copasetic. Look again, and damn if it didn't just happen: a gray film. They've turned inward, prayin' that if they don't look it will all go away. Hey soldier, you there? They just figured out they're about to cash in their chips, lights out. At ease, soldier.

I remember the day Larkin hit the wall, his eyes glazing over. Almost three years to the day, seems to happen that way. They come to the Rancho thinking this is a temporary thing, a major tune-up and I'm on my way. Just a matter of time before I get put back together and march outta here. By year two they're thinking OK maybe I'm not walking out of here, but I'm damn sure rolling out of here in a chair. OK, I can deal with not walking. Then it happens like clockwork in year three: they realize they aren't going nowhere. That the Rancho is as good as it gets: they're lifers. They look to the right and they look to the left and see D-Cube or Claymore or Tostenson -- the long-timers they thought were different. Suddenly they realize they're not different, they're in the same foxhole.

I was there, pulling night duty. What could I do? I held Larkin's hand all night, Japan popping off in my brain. Humming take it easy, take it easy, son.

It's been thirteen years since I've seen the ocean, steaming home on a navy hospital ship, explosions still going off in my head. I remember a son in Long Beach, and his mother, waving to me as I walked the plank and headed for the Pacific Rim. I will find them. My wheelchair and I will roll up the driveway, like a hero in his chariot returning from the Trojan Wars. I will bang the metal plate in my skull with my Bronze Star -- a drum roll for peace -- to announce that I am home.

El Conquistador

OK. OK, maybe that was a dream. You know, the part about the nurse's aide going down on me and all. Mi sueño. But, hey, man-- whatever it takes to keep you going. That's why I like the night the best, tied down with my dreams. Los sueños of what mighta been.

But maybe it wasn't no dream.

Nights do that to you, know what I mean?

To be continued...

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.