The burglary was hatched in Pudge's bar.

On a Friday night I was drinking with Lucus and Steve-o. I was new to Del Ray, and they were the only friends I'd made since my mother and I moved from Indiana. We had moved after my father took off, leaving us with three months unpaid rent and a rusty Honda with two bald tires. Fortunately, my mother's sister in California had better luck -- when her husband deserted her, he left behind a small motel laundry service with an upstairs apartment. My aunt invited us to move in with her; we had nowhere else to go.

Pudge had been running the bar ever since his father's emphysema prevented him from breathing through the curtain of smoke that hung in the air. Aside from replacing the bar's black and white TV with a color set, nothing had changed since Pudge took over. Most of the glasses were chipped or cracked, and the regulars knew to inspect their glasses before bringing the rims to their mouths. The bar's appeal was that Pudge never checked ID. If you could climb onto a wobbly bar stool, you could get a drink.

There was a ball game on the bar's new color TV. While a relief pitcher trod his way to the mound, my eyes wandered to the smoke slithering from Steve-o's freshly lit Pall Mall. Lucus and Steve-o were born in Del Ray, neighbors since childhood. They had grown together like tangled tree limbs. Steve-o was Lucus' protégé, and proud of the diminutive o that his mentor had placed at the end of his name. He had dark, sunken eyes and jutting cheekbones that made his skin look too tight. He was small for fifteen, and had to triple-roll his shirt cuffs and hitch up his stiff blue Levi's every couple of minutes. Steve-o struggled to wear this uniform because it was what Lucus wore.

Lucus was just out of high school, waiting around for his draft notice to show up. He seemed tall because he was bone thin and wore dusty cowboy boots with stacked heels. His light brown hair had streaks of dark red. He combed it back and tucked it behind his ears. Steve-o wore his this way, too.

Lucus was watching a beer commercial, but he was talking to me.

"So Nick, what else you see?"

I'd been aboard the Heidi Jean only once, so it was a struggle to add to the list I'd already given him.

"I think there was a radio, fishing stuff, a small TV, and a jar full of money."

On hearing the word "money," Lucus looked right at me. He wasn't big or tough, but he could run you through with his eyes.

Steve-o, not to be left out, asked, "How much?"

I wasn't happy about answering to a kid two years younger, but Lucus' silence told me I didn't have a choice. I gave Steve-o a short glance and went on,

"It was a big mayonnaise jar with about ten bills stuffed inside, maybe a bunch of quarters at the bottom."

Lucus leaned closer. "You sure you saw a fish finder?"

"Yeah, it's up on the bridge."

Lucus sat back with a satisfied grin. He fixed on a point just in front of my face and launched a perfect row of smoke rings.

"OK," he said, "Let's do it tomorrow night." He poured us fresh mugs from the pitcher, and the three of us clanked a badly-timed toast. I drank mine to the dregs in a gulp.

Late Saturday, the three of us met at the dock. Lucus and Steve-o were both wearing Navy surplus pea coats and dark watch caps. I had on my old tan parka and a red-and-white striped snow hat.

"What are you doing, building a snowman?" Lucus joked.

Steve-o snorted and laughed until he choked on his cigarette smoke. I wanted to run back to my aunt's house and bury myself in a mountain of white canvas bags, to breathe in the clean smell of freshly laundered sheets and towels. But I didn't run. I just stood there and forced a stupid smile.

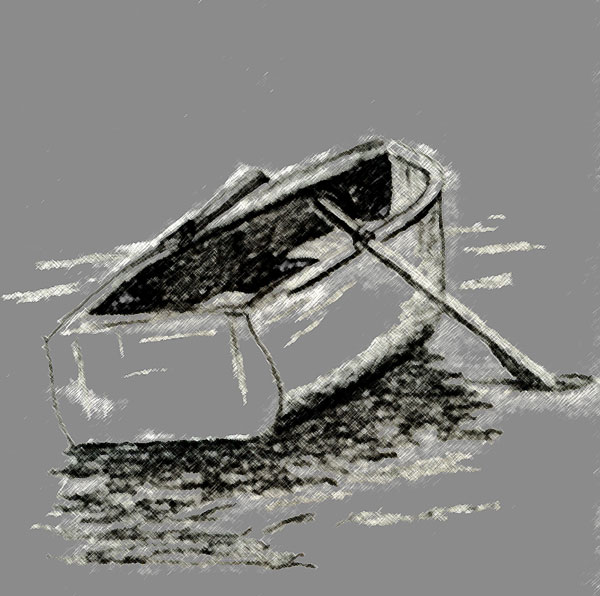

Under one of the piers we found a gray wooden rowboat chained up with its oars. Steve-o pulled a bolt-cutter from his small green backpack and gnawed through the chain in less than a minute. We boarded the boat and pushed off at just past midnight.

Lucus told me to row, so I sat down on the slippery bench next to the oarlocks. It was the first time I had rowed a boat -- I'd never seen a body of water larger than a swimming pool before I moved to California.

"Hey Popeye, you're sitting back-asswards."

Steve-o laughed before I understood what Lucus was saying.

"You can't row sitting that way. You got to face backwards or you'll row us up to the parking lot."

I swung around facing the shore and began to row. It was difficult for me to keep the oars pulling steady and even. We hadn't made much forward progress, and my shoulders were already starting to burn. "Get the hell off the seat. Steve-o is gonna row."

I changed seats and handed the oars to Steve-o. He smirked as well as he could with a cigarette drooping from his mouth.

The fishing boats were tied to buoys about 100 yards from shore. Stunted harbor waves slapped their fiberglass hulls. Cabin lights still burned from inside a few of them, but otherwise the night and the ocean were folded up in darkness.

When we bumped up against the Heidi Jean, Steve-o stood and grabbed the side rail to steady our boat. Then Lucus muscled up to the deck. I was the last to climb up, thankful that neither had seen me struggling to get aboard while the rowboat drifted away beneath my feet. I felt like Curly the Stooge.

When we were all on deck, the two looked at me like I was a map.

"Ok, Captain Hook, give us the tour."

Steve-o gave a laugh that choked him on cigarette smoke.

"I need to go use the bathroom," I said.

"Just do it over the side!" Steve-o whined.

"I can't. I need the bathroom."

Lucus looked at me crosswise. "It's called a head. You sure you've been on a boat before?"

I turned without answering and walked to the head. I knew what it was called, but I was so nervous I forgot.

So nervous I couldn't do anything in the head.

I had been on the boat during my first month in Del Ray. One of my teachers noticed me drifting aimlessly among the tight-knit groups at school and asked if I'd like to crew on his brother's charter fishing boat. The next Sunday morning I showed up early and waited in the wet, salty air until the captain and his two sons pulled up in a gray Plymouth van. The brothers were the regular crew, and though it was obvious they didn't need extra help, they didn't treat me like surplus equipment, either.

When the fishermen arrived, one of the brothers asked me to stash their tackle boxes, show them where the head was, and bring them hot coffee and donuts. It all went well, until we got underway. I'd never been seasick before. I'd never been at sea before. They had kidded me about it, but in a way that made me feel like I was one of them.

Lucus and Steve-o were already up on the bridge when I retuned from the head. I climbed up and found them at work trying to remove the sonar fish finder from the fiberglass control panel. Lucus was holding a flashlight for Steve-o as he unscrewed the mounting bolts. "Hurry up! You ever use a screwdriver before?" After a few seconds he lost his patience -- "Give me that!" -- and grabbed the screwdriver from Steve-o's hand. Lucus crammed the flat edge between the sonar and the panel and pushed down to pry it up. The sonar wouldn't budge. Growing frustrated, Lucus started kicking the panel with his boot and continued kicking until Steve-o was able to rip the sonar from the socket. The wiring straggled behind like entrails.

I wondered what the captain would say when he saw what we'd done to his boat.

Lucus turned to Steve-o. "Go down and look for fishing shit and anything else that's worth anything." He looked to me and said, "Show me the cabin."

I lead him down to the cabin door -- it was locked. "Kick it in," he said. I hesitated.

"There's a key behind the life preserver up on deck," I hedged.

"Just kick it, you pussy!" I closed my eyes and kicked open the door.

Once inside, Lucus searched around with his flashlight. There wasn't much to see. "Shit!" Then he saw the little black and white TV. The day I crewed the boat, the captain cooked us dinner and we sat around the galley table, eating and watching a game on its fuzzy screen.

Lucus picked up the TV and tossed it up a few times, and then heaved it like a basketball, shattering it against the far wall. He looked for my reaction.

"Why'd you have to do that?" I was surprised I said it.

He laughed and said, "Why do you care? You're the one who got us here."

A cold wave surged up my body, as I suddenly understood what I had done. I imagined the disbelief on the captain's face when he opened the cabin door and saw what they -- we -- had done. His confusion would become anger. Would he think of me? Now I was afraid. My legs began to tremble and a damp sweat settled on my forehead. The captain had treated me better than anyone else in Del Ray had. I repaid his kindness by destroying his boat, his livelihood. My gut felt worse than seasickness, and it wasn't going to go away when I left the boat.

Steve-o, drawn by the sound of destruction, scurried into the cabin.

"What was that?"

"Oops, I dropped a TV," Lucus smirked. "Find anything up there?"

"A couple of fishing reels, binoculars, and these." Steve-o held up a pair of bright yellow rain slickers. "One for you, one for me."

Lucus cocked his head and looked at him like he was a bug. "Are you stupid? Think we're going to walk around wearing those?"

Steve-o, not comprehending his sin, lowered his arms and the slickers to half-mast. "You don't like them?"

"They're great. Why don't we just walk around with a yellow arrow pointing to our heads saying, 'Hey, we're the guys who broke onto that fishing boat"?

Steve-o got it and dropped the slickers, kicking them toward me as if I had planned his humiliation. Then he brightened up and looked at me. "So where's the money jar, sailor boy?"

The crew's tip jar was under the galley sink. The day I worked on the boat, the two brothers split up the tips and gave me an equal share. I wasn't expecting such generosity, considering that I had been of so little help. I would have been happy with a couple of donuts.

Lucus had already found the jar. He called out my name and fast-pitched it to me underhand, yelling, "Hey! Think fast!" I didn't react in time, and the jar bounced off my chest onto the floor, sending broken glass and quarters flying in all directions.

They laughed.

Steve-o started to pick up the quarters that splashed at his feet. "Screw it," Lucus said. "Let's get out of here." They marched from the cabin without a second glance, leaving me to stand amongst the rubble.

On deck, the sonar, the fishing equipment, a pair of battered binoculars, and a turquoise portable radio were piled in a heap. Lucus began stuffing all of the gear into a duffle bag stenciled with the name "Heidi Jean."

Steve-o's voice racketed from over the side. "I can't believe this! How dumb can you get?"

Lucus looked over the gunwale.

"He didn't tie up the rowboat. It's gone," Steve-o yelled.

At first I didn't understand. Then Lucus snapped his head toward me. "You didn't tie up the rowboat, idiot. Have any brilliant ideas about how we're going to get off this boat?"

I stumbled a reply. "I didn't know that was my job."

"I didn't know that was my job," he mocked in a high, nasal voice and then in his own voice said, "Whose job was it? You were the last guy off."

"I didn't know," I repeated. Steve-o, back on deck, glowered at me. But his glare looked more like fear than anything, which consoled me a little.

"We have to swim back." Lucus was already taking off his boots. Steve-o began to remove his own without a momentary thought; he was hooked up to the same wire.

I looked across to the shore lights. It was 100 yards, but it might as well have been the entire ocean. I wasn't a very good swimmer -- I'd never swum farther than across the public pool and back.

They were down to their nearly identical boxers. Neither had said a word to me, or even thrown as much as a glance my way. They tossed their clothes and boots overboard and started to climb over the side.

Lucus looked at me. "I figured you couldn't swim," he said before his head dipped below the deck line. "When your captain shows up in the morning, you never heard of us. You tell anyone it was us and you won't be walking around Del Ray very long. Got it?" And with that, he disappeared into the water.

The splash of their strokes echoed back to me for a few seconds, and then the night was silent.

I still needed to use the head. Afterwards, I went back to the cabin and started picking up the broken glass and the quarters. I put the money in a cereal bowl, but left the remains of the TV where they were. Nothing could be done to make it right again. There were six hours before the captain and his sons would drive up in their Plymouth and then motor out to the Heidi Jean. I crawled into a bunk and fell asleep.

I dreamed that I was back home in Indiana, sitting at the kitchen table with my mom. The plates were set, but there was nothing to eat. Then I was in Pudge's bar. Someone brought me a dead fish. Its eyes were like white marbles and it smelled terrible. I was so hungry that I picked it up and ate it whole.

The harbor waves slapping the Heidi Jean's hull startled me from sleep. For a moment, I was an innocent. A young boy, new in town. This illusion vanished as I became aware of where I was and remembered what had transpired during the night. I squeezed my eyes closed, as if when I opened them I could be anywhere but the cabin of the Heidi Jean.

The porthole glass focused the morning sun, whose beams seemed to search the dark cabin for shards of glass, for the mangled shell of the TV and the unhinged door that I had kicked open.

The brass marine clock, somehow spared from the carnage, read 5:30 AM. The captain and his boys were at the donut shop now, placing their usual order of a variety of two dozen. They would sit at their favorite table, drinking coffee and pulling a few donuts from the bag. Five minutes later, they would hop back into their Plymouth, tune into the marine weather channel, and drive off, squinting toward the anxious ocean, bathing in the intoxicating scent of salt, fish, and diesel, searching for the first glimpse of their beloved Heidi Jean.

I made my way across the littered cabin floor and up to the open deck. The sea air revived me. I looked inside the bridge, where the gashed fiberglass and twisted wires glared like an empty eye socket.

The main deck seemed intact. Her sculpted body and proud bow gave not a grimace of the pain we had inflicted below. Scattered over the deck were the contents of the duffle bag my co-conspirators had left behind before they abandoned ship. I gathered the items and stuffed them back inside the bag. I kept the binoculars and scanned the shore for the dust of the gray Plymouth. It wasn't in sight -- maybe they had stopped for gas or for a dozen of the cheap cigars that the captain gave to fishermen when they landed their first whopper.

I sat on the beer cooler and thought about the moment no more than fifteen minutes away. I rehearsed my lines but soon gave it up -- there are not enough ways to say, "I'm sorry." Then, the calming calls of circling gulls were broken by a hard, rattling sound, like that of a hinged door banging in the wind. It continued in a steady rhythm and drew me to the port side rails. The sound was louder there. I shielded the sun from my eyes, searching for its source.

The first clue was a rope tangled up with a small, red and white channel buoy just fifty feet off starboard. I followed the glistening rope back towards the hull. Leaning far out over the rails, I saw that the soggy rope was attached to our long lost rowboat. She must have drifted free until the rope (that I had neglected to tie) caught itself up in the buoy's anchoring chain, which effectively ended her escape. The boat had been pulled back by the reversing tide and was now held tight against the hull of the Heidi Jean, like a wet dog on a leash.

And so she had come back to save me. She would forgive me -- she would take me back to shore. A pardon. Another chance. A merciful redemption.

Then I spotted the Plymouth bumping across the dusty parking lot. I could row a diagonal course until I was close enough to swim the short distance to shore. On the beach, I would ditch my shoes and shirt, roll up the cuffs of my jeans and scour the shoreline, an innocent young boy searching tide pools for sea urchins, snails, and mussels.

I could escape but I couldn't run away from the Heidi Jean. I always knew the reason why I did what I did. But until I climbed into the rowboat, I didn't understood what a stupid reason it was. I looked toward the dock just as their old boat coughed up a haze of smoky exhaust. I could make the shore but I had to go right then. That's what I did.

05/21/2012

10:29:22 PM