-1-

"There should be a law," said Jim Kingsley without a trace of irony, "a law of nature as well as a law of man, something written into the fabric of the cosmos and human consciousness. People should get married only after they turn thirty. A simple, almost innocuous injunction, don't you think? Especially for men. They need a certain amount of wisdom before taking the wedding vows, certain kinds of experiences, awful experiences, to harden the soul before a long, brutal winter."

"A long, brutal winter ..." Grace repeated. "Is that how you see marriage?"

As an associate professor of comparative literature, Jim had fallen into the habit of thoroughly analyzing every subject that might potentially have some bearing on his ambitious work-in-progress, a scholarly tome exploring the influence of Madame Bovary on contemporary culture, and he had to keep reminding himself that Grace, as someone who was unread and unaccustomed to the way he framed every topic of conversation as an argument, was never quite certain if he was joking or being sincere. It had something to do with the pitch and timber of his voice, the way the final syllables of each enthusiastic syllogism reached a manic falsetto, and he tried to compensate for this "affliction," as he came to think of it, by employing the banal phrase "I'm being perfectly serious," which only confused his doubtful listener even more.

Grace patted his hand the same way she would if she were trying to calm one of her pouting children and said, "Maybe you're right, but there are exceptions. Steve and I got married when we were only twenty-one, and I think things have worked out alright for us."

Now it was his turn to wonder if she was joking or being serious. She was ten years his junior and he made the mistake of speaking to her like she was one of his graduate students. "Would you care to elaborate?"

"I mean, at twenty-one most people are going through late adolescence," she said, "and an adolescent should never make big decisions, not about things like marriage or having babies. But Steve was always strongly opposed to cohabitation. Living in sin, he called it. It wasn't an option. We had to be married first. That's what you don't understand about my husband. He's old-fashioned, conservative, religious. To him sin isn't an abstract, philosophical concept. It's a real thing. He smells it in the air he breathes, tastes it in the food he eats. First thing in the morning, he has a healthy serving of sin and skim milk."

They strolled along a wide gravel pathway in the park, passing under a green archway of ashes and maples that shaded them in arboreal innocence, their contemplative voices dampened by the distant rumble of tractor trailers on the main road and the roar of lawnmowers as a ragtag army of sunburned landscapers descended on the nearby campus. Jim pulled his son Charlie in a red wagon, and the boy, just turned three, babbled happily to himself and sometimes slapped the sides of the wagon, hoping to make it go faster, faster. Grace's twin daughters, Dawn and April, followed close behind on two squeaking tricycles, and for once they did not continually interrupt the conversation like a couple of old-maid chaperones with the demands of the chronically cranky and incontinent: "We're thirsty, we want some juice, we're tired, we need to go home."

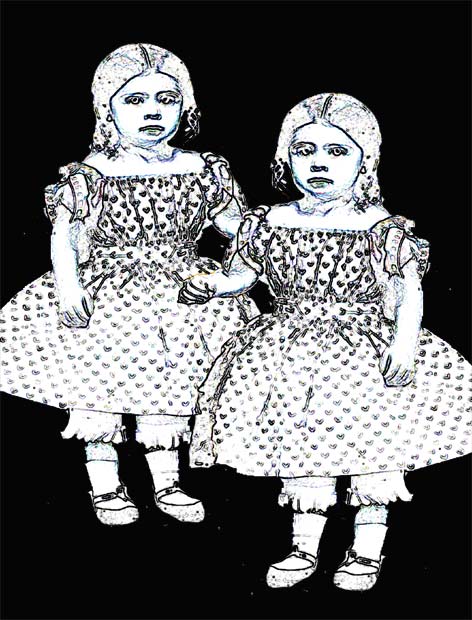

Jim had never really warmed to the girls. He found them to be not merely obnoxious and irritating, which is how he characterized most children, but abnormally sinister. At five years old they were, like their father, thick, solid, almost pudgy, with dark, menacing eyes. They were also accomplished mimics and delighted in mocking adults, especially "Plucky Prolixy Professor King-silly," aping his vocabulary with uncanny precision in a single sing-song voice and then, when he shot them a weary and wounded look, squealing with malicious, porcine laughter. Two terrible, tittering tormentors, they teased Charlie, too, pinched him, pulled his hair, stomped on his tiny toes, but it was for their long-suffering mother that they reserved the brunt of their wickedness. They relished their roles as jailers, persecuting her in ways that only the most hard-hearted of wardens can. They intuitively understood that parenthood was a kind of indefinite prison sentence, one in which adults, as a general rule, spent most of their days sequestered from other adults, and from the moment they burst from the womb the girls seemed to prattle a maddening refrain: "We condemn you, Mommy, to a decade of solitary confinement."

Because her husband was away from home six months out of twelve, Grace was more isolated than most adults, and the long, lonely days left her stooped over, beaten down, a sad spirit with a haunted look on her face. The high-pitched, explosive, and largely unpredictable tantrums of her children made her desperate to hear the voices of other rational human beings, to have a conversation about something other than Popsicles and cartoons and imaginary friends who lived in troll-infested forests.

Jim recognized how acutely she suffered and was only too happy to offer her an occasional reprieve from the lunatic asylum of her home. In the summer he was transformed from a promising, young professor into a stay-at-home dad, and because he wanted to escape from his house as much as she wanted to escape from hers, he invited her on long walks through town. Sometimes, as they ambled through the park on these sunny afternoons, he imagined how they must have looked to strangers -- a happily married couple with three adorable children -- but in a small college town, where there were few strangers and gossip was ubiquitous, one quickly learned that discretion was a game that everyone was compelled to play. The rules were simple enough to master: never walk too close together or accidentally brush up against each other or look each other directly in the eye.

Now, as they made their way toward the fountain in the center of the park, Grace's girls, without asking permission, raced ahead and thrust their hands into the water to scoop up the shiniest pennies so they could make wishes. Sensing trouble, Jim led Charlie over to the swings. Grace tried to convince the girls to sit nicely on the stone ledge, but April and Dawn shrieked and accused her of trying to push them into the water where "a great, big, electric-blue jellyfish" lurked in the shadows, waiting patiently to sting any silly children who happened to fall in. After a few minutes of unsuccessful negotiating, Grace gave up the effort and joined Jim at the swings.

"Well, there is definitely one thing you forgot to consider," she said in exasperation. "If people married late in life, there would be very few children in this world, that's for sure. The older you get, the less patience you have."

Jim nodded. "Ah, yes, this was nature's big mistake. It's an engineering problem, really. If nature could reason properly, if it weren't so blind, it would have made us capable of reproduction beginning in middle age, not before. Think of all the problems that would solve."

"Are you saying fatherhood doesn't agree with you?"

He pondered this for a moment, and for once his voice did not reach its normally frantic pitch. "I'm not sure men, especially young men, are cut out for the job, that's all. You wouldn't trust another man with your children, would you?"

She smiled and gently squeezed his arm. "I trust you, Jim. I do."

He shuddered, and for a moment he thought it was because he felt an electrical charge from her fingertips surge up his spine, but then he realized that April and Dawn, throwing fistfuls of pennies into the fountain, had resumed their infuriating imitation of "Pontificating Professor King-silly" and were singing a sardonic refrain: "Something to harden the soul, something to harden the soul, something to harden the soul before a long, brutal winter."

-2-

At noon they loaded the kids into her minivan and drove back to her house.

They had lunch together at the small kitchen table, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches made in haste. After wiping sticky mouths and fingers they put the kids in front of the TV. They waited for the children's eyes to grow heavy with exhaustion, then they rushed hand-in-hand upstairs to the master bedroom where in the stifling summertime heat they made love. With any luck they would be able to lounge in bed for an hour or two, talking quietly about their lives and caressing one another beneath the sweat-soaked sheets. They attributed their affair to the obvious -- they were lonely, discontent with their marriages, desperate for some eroticism, spontaneity, adventure -- the sorts of things one was expected to say at such moments, or so Jim believed. Part of the proverbial script. In fact, he didn't feel this way at all and was quite content with his marriage. For him this affair was purely recreational, a diversion, nothing more. He had no interest in a long-term commitment and suspected Grace felt the same way.

"Steve will be coming home in a few weeks," she said, her eyes shifting toward the doorway. Her voice, though small and distant, seemed to fill the whole room. "He'll stay from early July until early October. So I'll have more help with the girls. But you know how Steve can be. He'll remind me that he's on vacation, that he's been working hard and deserves a break. Maybe he'll watch the twins for an hour or two while I make a quick trip to the grocery store. But even that's asking a lot."

"Not the type to entertain the kids for an entire day, is he?"

"Not even a trip to the zoo."

Steve was a merchant marine, a simple deckhand who spent half the year on an iron ore ship cruising the Great Lakes from the Port of Cleveland to Mackinac Island to the remote Canadian outposts dotted along Lake Superior. During this time Grace was trapped in their suburban cape cod, raising their two daughters and "gradually losing her shit," as she frequently put it. She had no family in town, and in the bleak winter months she rarely managed to flee her captors. Her situation didn't much improve when Steve was home.

Sometimes at night, when Jim was quietly working in his study, he heard screaming and shouting and then sudden, ominous silences. He'd long suspected Steve of abusing her, of slapping and shoving her up against walls and doors, pressing her face against the floor. In July, when everyone else in the neighborhood wore T-shirts, Grace wore long sleeves, and once Jim thought he glimpsed a bruise on her left arm, the purple indentation of fingers pressed hard into pale, delicate flesh. It wasn't his business, he told himself, but now he wanted to know what kind of people lived next door to him. Neighbors were an indication of one's own status, and Jim worried that he'd slipped yet another notch in the socio-economic ladder, that despite his proud middle-class bearing he was just another anonymous wage earner like Steve, struggling to eke out a modest living in this slightly shabby quarter of the town.

When she heard his theory, his wife Nora scolded him for these unfounded allegations and his snobbery. "You do know that rich husbands beat their rich wives, too," she said. "Rich or poor, men are capable of monstrous behavior."

Her response startled him. He expected some rhapsodic affirmation of their superiority, a lovely ode to their granite countertops and stainless steel appliances and the reassuring smell of ammonia and fresh cut flowers.

"Oh, come on," he said, "you have to concede that statistically speaking, people without money are far more likely to be abusive. And let's face facts, our neighbors have very limited means. Their house is falling apart. Hell, half the windows are cracked. The shingles are peeling off the roof. I'm surprised the city doesn't fine them."

Nora rolled her eyes. "For godsake, Jim, their house is perfectly fine. It just needs a little work. Grace is alone over there. You can't expect her to fix the place up. Steve will get around to it eventually. Besides, our house isn't exactly a palace either. Maybe you should worry a little more about the things that are broken around here."

Nora was probably right, she usually was about these things, but Jim remained skeptical and felt that any house in advanced stages of deterioration was a bad omen.

Now, as he lay in bed with Grace, he began his methodical inspection. He looked at the cracks in the ceilings and the damaged plaster walls. He noticed the crumbs scattered on the hardwood floors and the candy wrappers poking out from beneath the bed. Then he leaned over and kissed Grace's neck, breasts, stomach, naval, thighs, slowly searching her soft skin for telltale signs of abuse.

"The kids will be up soon," she said, pushing his head away. She reached over and grabbed a pack of cigarettes from the nightstand. Grace had impulsively purchased the cigarettes one day while on one of their walks, and Jim had beamed at her with admiration. He liked the fact that she had a seditious side to her nature. Apparently, smoking was one of those things that Steve strictly forbade in his home -- an idiosyncrasy for a workingman. She handed one to Jim now, and he suddenly wondered which would bother Steve more: that his neighbor was screwing his wife on a regular basis or that he had the effrontery to smoke in his bed?

"Your thirtieth birthday is tomorrow," he said. "I made reservations for seven o'clock. Do you like French food?"

"Dinner?" She inhaled deeply. "That sounds nice. But who will watch the girls?"

"I told Nora that you wanted to go out to celebrate with some of your friends, and she agreed to take the twins. She's only too happy to do it. She loves those girls, you know."

"That's very nice of her." She rested on her weight on one elbow and looked at him. "And how about you? What's your excuse for leaving the house?"

"The usual. I have to go to the college library to work on my manuscript. I need absolute quiet in order to concentrate."

"Ah, yes, what did you call it? Your magnum opus?" She got up from the bed and walked across the room to her dresser.

He laughed, marveling at the silhouette of her naked body against the white blinds. "Well, modesty never got anyone anywhere. So? Will you go on a date with me?"

"I'm not sure."

"Why? What's the matter?"

"All of this sneaking around," she said, opening a drawer. "It's not fair to Nora. And besides, I don't have anything to wear. Look at this wrinkled, old thing." She lifted a black dress from the drawer and held it up to her torso.

"You're sexy in whatever you wear."

"Are you trying to be funny?"

"Listen, Grace, you deserve a night out. Something civilized, romantic. A little wine and candlelight. It's not like we're doing anything criminal."

She sighed. "Don't you feel guilty? Don't you feel like a cheat, a lowlife? Sooner or later ... "

"What?"

She yanked open the blinds and squinted in the hot sunlight, but before she could finish her thought, there suddenly came from downstairs, like the jarring blare of an alarm clock, a sharp cry from Charlie followed by the ghoulish giggles and conspiratorial whispers of April and Dawn.

Jim clamored out of bed with a groan, disappointed as always that another blissful afternoon had come to a premature end.

-3-

The restaurant, a trendy French bistro on the outskirts of town, was crowded with young couples, many in their twenties, some probably graduate students at the university, and Jim, as he waited near the entrance for Grace, worried that someone might recognize and expose him. He checked his watch again -- she was already thirty minutes late -- and he slipped quietly outside to the patio bar where the heat and humidity kept most of the patrons away. He ordered a scotch, neat, with a glass of water, and watched the cars speeding along the main road. From here he could keep an eye out for Grace's white minivan and listen to the distant, discordant sounds of tolling church bells and police sirens.

Sitting alone he felt like a fool, a jilted lover, and the anger and humiliation must have shown on his face because the bartender avoided making eye contact with him. Maybe Grace was right, maybe all of this sneaking around wasn't worth the trouble, women were much better than men at detecting moral depravity, and he worried that this affair, his first one, had abruptly ended in total failure. He ordered another scotch, a double this time, before an apologetic maître d' slunk towards him to say that his reservation had been invalidated. Jim grunted. He finished his drink and then ordered another. He waited fifteen more minutes before throwing some money down on the bar and staggering out of the restaurant. Racing recklessly back to town in the dark, he was startled by how quickly his feelings for Grace had gone from lust to hatred, and he forced himself to concentrate on the winding road to keep from weaving.

When he arrived home he found his wife at the kitchen table, sobbing loudly and clutching a box of tissues to her chest. There was a manic look in her eyes. So Nora knew. He could only surmise that Grace, overwhelmed by guilt, had confessed everything to her. In a flash he envisioned a million scenes of pure misery, saw himself sleeping on a friend's couch for the next month, living out of a suitcase, renting a rundown studio apartment on the other side of town, consulting an incompetent attorney with a jiggling belly and a bad comb over, standing before a judge whose eyes were glazed over with boredom, the hundredth divorce or disillusionment he'd heard that day. Worst of all he pictured the confused look on his son's face when he tried to explain the concepts of separation and divorce.

"Nora," Jim whispered, "listen ... "

His wife choked. "It's so senseless."

"Let me get you some water."

Her hands trembled so badly that she could barely hold the glass without spilling it.

"We'll get through this thing," he whispered hopefully.

Nora looked at him with astonishment. "What about the girls? What about Steve? What are they going to do? Those girls, they're just babies. They need their mother."

Jim had always considered himself a great perceiver of life's details, a serious thinker profoundly influenced by the Flaubertian method of conscientiously chronicling the quotidian, but now he realized that in many ways he was a typical male and therefore an emotional invalid unable to pick up on subtle cues, even obvious ones. Though it took a moment, it finally occurred to him that he was missing some important and consequential fact, that he wasn't interpreting this scene correctly, that there was, if such a thing were possible, something far worse than an act of infidelity troubling his wife.

He sat down beside her and held her hands. "Tell me, Nora. What's happened?"

The facts poured out of her in a breathless stream. The police, she said, came to Grace's house tonight. From the kitchen window Nora saw their glum faces as they plodded up the driveway to the front door. She went over to see if she could be of any help, explained the situation to them, told them that she was watching the girls while their mother was out for the night and their father was working out of town. The officers stared at their shiny black shoes, pinched their chins, scratched their prickly heads. With reluctance they told her that there'd been an accident, a white minivan smashed against the median, overturned, crushed under the weight of a tractor-trailer. Beyond that they refused to give her any more facts, would say nothing about the condition of the driver.

Nora squeezed Jim's hands until he winced in pain. "They needed to speak to the next of kin," she said. "That was probably a mistake, letting that little phrase slip. Next of kin."

Jim blinked. He wanted to grab his wife by the shoulders and shout, "What the hell are you talking about? Start making sense!" But he found that he could say nothing at all.

Nora pressed her face against his shoulder and moaned, but after a minute she pulled away from him and with tears streaming down her face asked, "Jim, have you been drinking tonight?"

-4-

During the wake a long line of mourners shuffled solemnly through the funeral parlor, and Jim, waiting his turn to offer his feeble condolences, was forced to contemplate the macabre rituals of grief and interment. It was his understanding that a distraught widower, when faced with an unexpected loss, eventually cries himself out, that he becomes so emotionally exhausted that he is unable to shed even one more tear, and perhaps this was the case with Steve because, each time a sobbing friend or family member approached his wife's open casket, he thrust his shoulders back, lifted his chin, and with unbending stoicism gave either a quick hug or a perfunctory handshake. He spoke barely a word to anyone and stared straight ahead, his eyes empty, purged of all emotion.

As he moved ever closer to the casket, Jim felt nauseous, lightheaded, and for one terrible instant believed that he smelled something low and sour, a pestilential odor that wafted from the corpse. Though he promised himself he wouldn't do it, he felt his burning eyes drifting toward the shattered, twisted shape laying in the box, the folded hands as stiff and artificial looking as those of a porcelain doll, the rigid face caked with makeup. A small, strangling sound escaped his lips. Could this be the same woman he'd made love to only a few days ago, the woman who offered herself to him day after day during the month of June?

He lurched forward and heard his wife speaking. "If there is anything we can do for you and the girls, anything at all ... "

It took him a moment to realize that he was standing face-to-face with Steve and that the two were now shaking hands. Thick in the chest and broad shouldered, Steve seemed a much more imposing man than he really was, but today he appeared shrunken and defeated, and it was with great relief that Jim realized the offending odor belonged not to Grace's disfigured form but to Steve and concluded that the man hadn't showered since arriving home for the services.

"I want to thank you, Jim," Steve said. "I know how hard it must have been for you to call."

Jim muttered something inane and platitudinous.

"I'm so sorry you had to find out that way," Nora told him, stroking his arm. "It's not fair. Grace was such a lovely woman, so warm and friendly. I just don't understand why this is happening to you and the girls. Oh, those girls."

On the night of the accident the twins slept in the guest room, blissfully unaware of their situation, and for a long time Jim sat alone in his study, thumbing through his manuscript and gazing at the books on his shelves, hoping to find a title that might offer some kind of wisdom and delay the inevitable for just a moment longer, but by procrastinating he was only torturing himself. Out of habit he reached for his dog-eared copy of Madame Bovary, but he couldn't make sense of it, the words were suddenly indecipherable, the meaning obscure, and he abandoned any effort to read it.

Grace kept a spare key under a rock in the flowerbed, and Jim entered the empty house through the back door. He rifled through the disordered papers on the kitchen counter until he found an index card tacked to a corkboard with the carefully printed words "In case of emergency" and a phone number. "God help me," he whispered. That's when he did most of his crying, in a quiet place where his wife wouldn't see him. He slumped into a chair and bawled like one of the children, a wretched, inconsolable wail, alternately cursing and pleading stupidly with the silent forces that controlled the cosmos. When he came out of his daze, he wiped away his tears, picked up the phone, and his voice, strong and unwavering, reached the iron ore ship three hundred miles away on Lake Michigan.

"I want to thank you," Steve now repeated. He shook his head slowly back and forth, and when he spoke again his throat sounded raw and parched, the voice of a man who'd been drinking whiskey for days on end. "There's just one thing I don't understand. When they pulled Grace from the wreck she was wearing her best dress, 'the black number' we used to call it. Whenever we went to a wedding reception or a New Year's Eve party she wore it. Special occasions only. I'm not sure what to make of it. I suppose she was pretty lonely. I guess maybe I do know that."

Nora said something about Grace's birthday, that she made plans with her friends, that a woman wants to look nice sometimes, but Steve didn't seem to hear her.

Leading his wife away, Jim said, "Look, if you need anything, Steve, anything at all, please don't hesitate to stop by the house."

Though badly shaken, Jim felt that things had gone as well as could be expected, but as he and Nora greeted some of the other neighbors and spoke to them in a far corner of the funeral parlor, he grew uneasy and couldn't help but notice how Steve, who was ever more quiet and grim, occasionally looked in his direction, his eyes small and hard and filled with grave doubt.

-5-

During the rest of that terrible summer, Jim Kingsley tried to lose himself in his work. After putting Charlie to bed for the night, he would slink off to his study in the back of the house to consult his voluminous notes on Flaubert, scanning the marginalia scribbled there over the years. For weeks his work had languished, but now, after Grace's tragic demise, he was determined to leave some lasting mark on the world, some evidence that he had once been here. He also wanted to make his wife proud of his accomplishments and leave a legacy for his son, but as he sat at his desk he found it increasingly difficult to focus on the laborious revisions that needed to be made. Each night, above the restful chirping of crickets, he heard a door creaking open and the sound of heavy footsteps plodding across the backyard. Through the blinds he glimpsed Steve sitting in an Adirondack chair and staring up at the sky. For hours the man sat there like a stony-eyed gargoyle, one hand gripping a bottle of whiskey, his lips moving wordlessly. Before vanishing back into his house Steve tossed the empty bottles in the tall grass.

This ritual continued without variation all through the summer and fall, and by December the back yard was littered with bottles of booze, a kind of testament to Steve's unceasing anguish. Then one unusually frigid evening, a week before Christmas, a knock came at the door, three dull thuds that resonated with meaning, a distinctive knock that made Jim leap out of his chair with a startled cry. Outside, standing on the stoop, Steve stomped his feet and vigorously rubbed his hands together. He wore his usual workman's clothes -- a filthy flannel shirt, faded jeans and steel-toed boots. Lurking behind him were his girls, their hair matted, knotted and greasy, their features dulled by layers of grime, their lips chapped and frozen into tiny, contemptuous smirks. Jim hadn't seen the girls since their mother's passing and was beginning to wonder if they had crawled inside the coffin during the wake and were now buried with her in that forlorn cemetery by the river.

When she heard the knock, Grace came bounding from the kitchen. She knelt down to take the girls in her arms. "Well, look who it is! Come in, come in. Are you hungry? You look hungry. We were about to sit down to a late dinner."

"I'm sure the girls would like a hot meal for a change," Steve said.

"Of course they would. You too, Steve. Come in out of the cold."

He waved his hand. "Nothing for me, thanks. Go ahead girls. I'm gonna stay out here and have a smoke with Professor Kingsley."

Jim blinked. "I didn't know you smoked," he said skeptically. With great reluctance, he put on his coat and joined Steve outside in one of the Adirondack chairs.

The first blast of artic air had descended on the town, and a thin layer of snow sparkled in the Christmas lights on the neighborhood houses. From his shirt pocket Steve produced a pack of cigarettes, and Jim was startled to see that it looked like the same pack Grace had left on her nightstand the day she died. In silence the two men smoked the stale cigarettes. After a long time Steve finally spoke, and despite his ragged appearance, his voice had an unsettling clarity.

"I'm shipping out after the first of the year. I need to get back to work. It'll help me to get my head straight again. But I don't want to send the girls away to live with my sister downstate. I'd like them to stay here and go to school with their friends. Things have been hard enough for them. A move in the middle of the school year would just be another damn trauma. I haven't been much help, I'll admit that. I was on one helluva bender for a while. But I feel a little better now, I think."

Jim cringed against a sudden gust of wind and tried to focus on a lifeless brown leaf twirling at the base of an oak tree. It occurred to him that he had very nearly succeeded in erasing the memory of his affair with Grace from his mind, had almost exorcised her spirit from his life, and though he was not a religious man and seldom attended Mass, he suddenly felt her presence now, it was unmistakable, and suspected that she had been standing there all along, listening to her husband speak, maybe even making him say the words, her arms crossed, her mouth twisted into a vicious scowl, her eyes blazing with hellfire.

"I don't know how to ask this," Steve said, "so I'll just come right out and ask. Would you and Nora be willing to take the girls in? You're such good people and the girls love you to death. They especially love Charlie. Like a brother." He crushed the butt of his first cigarette out beneath his boot and then lit another. "I'm not asking you to support my children financially, understand. Money isn't the issue here. I'll transfer cash into your account every week."

A feeling of bitterness crept into Jim's heart. This was unfair. He wanted to move on with his life, wanted to enjoy the holidays in peace with his family. He lifted his eyes and looked at the neighborhood houses, and it seemed to him that every Christmas tree looked like a burning bush, as if each potbellied, middle-aged, American man was Moses, and in order to receive a daily dose of divine revelation he need only step through the front door, remove his shoes, and shout, "Here I am!"

"Jim, would you please think about it for a day or two? Talk it over with Nora? The girls feel safe here. It's almost like home to them."

Steve stood up, brushed the ashes from his pants and, without saying goodbye, trudged back to his house. Jim stared at the trail of footprints in the snow, and the longer he stared the more he thought he saw another set of prints beside his. In the cold night air he shuddered and waited for something to happen, for a limb from the oak tree to come crashing down on his head and kill him. After a moment he returned to the warmth and light of his study, but on the back of his neck he felt an icy breath and heard those two maddening voices in the kitchen, repeating a perverse and familiar refrain.

" ... Something to harden the soul before a long, brutal winter."

06/10/2012

02:48:29 AM