Chapter Six: On Their Own

Over the next few days, Henry Ma seemed to be taking the delegates' complaints to heart. Maybe he had seen their point, or maybe he had been planning on doing this all along. Certainly he had calculated how many more round-trip tickets to China his wife would sell if each delegate found a project or personal connection he or she wanted to pursue in Yutian. Whatever the reason, he and Mei Li held several discussion sessions with the delegates in the private dining room at the Rits. ("You realize why they have us using this one room all the time," commented Mike. "It's probably bugged." He looked pointedly from Mei Li to the light fixture above their heads. No one was putting anything over on him.)

From these discussions, Henry gained an idea of who in Yutian each delegate was interested in meeting, and then with the help of the local government he arranged introductions and visits. Everything was coordinated through a small, nervously-efficient, English-speaking government official who sat in on all the meetings, and whom the delegates privately dubbed "the 'droid." He spoke, dressed, organized, and even smiled very efficiently, but he froze up instantly whenever Mike or someone else raised an issue that was only slightly sensitive -- as when Mike asked if the Gu people had rights equal to those of the rest of the population of Yutian, and when Tony wondered if everyone in Yutian had an indoor toilet.

"Of course," the official would answer, unblinking, as if a button in the back of his head had been pressed. Mei Li would look pained, and Henry Ma would gloss everything over with a quick "hahaha" and a change of subject.

"What a complete Party hack that little guy is!" Mike would exclaim later at lunch, to his fellow delegates and the light fixture.

But the happy result of all these meetings was that now everyone had somewhere interesting to go. Also, the city soon became a more familiar place as the delegates came back from their various excursions and shared their discoveries with each other. They described all the places they visited -- the local history museum, a factory that made electric bicycles, a grassroots recycling project, classrooms full of smart school kids, a handicraft market -- and someone had even found a place that served Vietnamese iced coffee. As each delegate related his or her experience, the others were eager for all the details:

"How do you get there?"

"Are there English labels on the displays?"

"Near the Mao statue? But haven't we seen four Mao statues?"

"Do they have cappuccinos?"

They became increasingly bold about setting off on their own, although it made Mei Li a little nervous. She reminded everyone to be careful at the intersections, and each morning after breakfast, Sheldon coached them on the most necessary Chinese words. He drilled them without troubling them about what the words looked like in western spelling or in Chinese characters. They went completely by sound:

"SHAY SHAY is thank you; JA NA DA is Canada; BOO is no; BOO YOW is not want; JIGGA is this one; PEE JOE is beer."

"That one's easy to remember," snickered Mike.

The conversation-starter at dinner became, "You won't believe where I ended up today!"

Mayor Drucker, Jack, Tony, and Doug met with government officials, factory owners, and businessmen anxious to show them around and form exchanges with Canada. They visited the Fermented Bean Curd Factory Number One, of course ("There was only one part where the smell was really bad," the mayor reassured the others), and the enormous electric bicycle factory. But what they couldn't stop talking about was a recycling program that started with people young and old on tricycle carts hauling stuff from every corner of the city.

"They don't miss one pop can!" Tony exclaimed, deeply impressed. "Every single thing is put to use and all they end up with is a fertilizer that looks like puppy chow and water for watering the parks and washing the city busses."

Betty, although she was also a member of the business community, had a more specific interest in women entrepreneurs, and through Mei Li she discovered a young woman named Wei Wei who ran a stationery shop and fruit stand in an alley downtown. Betty took a liking to her right away. She was impressed with the tidy little shop she ran in a space about the size of the main bathroom in Betty's house in Wheat City.

"She has such beautiful fruit, and the stationery is geared to school kids -- notebooks, pens, every kind of cartoon-character eraser -- and she also has a photocopy machine. She's very smart and she knows a little English from high school -- and she has her baby right there in the shop, too." Betty sighed. " I wish I'd been able to do that. And I could have, of course, there was nothing stopping me, I was the boss. But I didn't allow myself to ... "

Betty spent several afternoons in Wei Wei's shop, sitting on a stool watching her do business with one hand and mother her baby with the other. And Wei Wei garnered a lot of extra customers with a foreign lady on the premises. Crowds gathered when Betty pitched in with the photocopying ("Come quick -- a foreigner is working here!" the word went out) , and giggling school kids dared each other to practice their English on her "GUDAFF-TERNOOON, LADY! HA-WAH YU?").

As for Sheldon, after paying visits to several local schools and laying the groundwork for a pen pal exchange between some Yutian English classes and Chief Stone High School, he indulged himself by hiring a car and driver to take him out to the nearest Gu village, to investigate the dialect. Mike tagged along because, he said, he missed going places in a car, and also because Sheldon was the only delegate with whom he could imagine spending a whole day. But Trish guessed he also had visions of a paradise of Gu girls.

When the two of them returned from their first day in the countryside, Sheldon was ecstatic. The Gu dialect bore intriguing similarities to a southern Chinese dialect he already knew. But Mike was a little down.

"The whole place was full of old people," he complained. "All the young people work in the city, so it's kind of quiet. And hardly any of the old people have teeth," he added irrelevantly, but that seemed to have left an impression. "They really need a dental plan."

Still, Mike said, the culture in the village had been kind of interesting -- the temples, the clothes the older women wore, the artwork on the village walls and so on. He could tell it had something in common with Tibetan culture.

"Sheldon said it could have come down here by way of the river." Mike was keen on everything Tibetan, and he liked to bring that up whenever Mei Li was around. "I've read a lot about that," he reminded her once again, at dinner. "Travel books, stuff by the Dalai Lama. Or is it illegal to mention his name in China?" He gave her a provoking smirk.

"I think he is on the cover of Newsweek just now," she answered coolly. "I noticed it in the hotel shop." Listening to the two of them was like watching swordplay, thought Trish. She just hoped there wouldn't be any blood.

Jerome and Rudy were also interested in exploring manifestations of religion in Yutian, but they handled their inquiries more delicately. They had checked the city map and located two churches that they hoped to scout out, one Catholic and the other Protestant: St. Joseph's Cathedral and the Yutian Christian Church. Henry, eager to be helpful, had responded to Jerome's request for the name of a priest attached to St. Joseph's.

This quest had piqued Trish's curiosity more than the bean curd factory, Wei Wei's shop, or the geriatric Gu village, and she decided to join them on their outing the following day. As Mike kept reminding them, religion was supposed to be incompatible with communism -- yet here on her city map, near the center of town, were these two blue dots marked "church," right along with the other colored dots that marked "Workers' Square" and "Museum of the Revolution." She was attracted to anything that went against preconceived ideas; also, she thought her Wheat City readers would be interested. There was a St. Joe's in one of the older neighborhoods at home -- maybe the two parishes could develop a connection of some sort.

Trish herself was a "lapsed Catholic," although she wondered if people even used that term anymore. So many things had lapsed in her lifetime. But it would still interest her to find relics of her childhood religion way over here in China. And of course it was always enjoyable to spend time with Jerome. He raised the intellectual level of the group, and she loved his dry comments.

The next morning she, Jerome, and Pastor Rudy made their way through the humid haze along the riverside toward the center of town. There, the main landmark was a vast paving-block square with a giant likeness of Mao at its center, standing up to his ankles in red petunias. Off on the various side streets were the usual banks and optical shops, one large and serviceable department store that called itself The Shopping Center, in English (Betty hadn't been hallucinating), a lot of cheesy smaller stores, and several outdoor markets that looked more interesting than the stores, except for the smelly one that sold live chickens and violent-looking slabs of bloody meat hanging on hooks.

On the map, the Yutian Christian Church was located just one block west of the square, so it wasn't hard to find. It was a modern, dazzlingly white building with vertical ribbons of glass for windows and a stubby steeple at the center of the flat roof. Four-foot high block letters along the roofline shouted out "Christian Church" and above these, at the top of the steeple, loomed an unlit neon cross. Trish just knew it would be bright red at night.

"So much for low-key religious activity in China," said Rudy, a little overwhelmed, craning his neck back to take in the huge letters. "I read that they had underground churches here. But this is above ground, with a vengeance. At Good Shepherd we could never put up a sign like that. The neighborhood wouldn't allow it." He sounded slightly miffed.

"It must be the sanctioned Protestant church," Jerome guessed. "With government backing -- and probably a lot of money. Remember, Henry said it's officially called the 'Patriotic Protestant Association,' and the Catholic church is the 'Patriotic Catholic Association.' I'd bet they can put up whatever signs they want."

"It certainly wasn't built with bake sales," observed Trish. She jotted down a few notes.

They climbed the impressive white staircase, hoping the church was open. One of the heavy glass doors was unlocked, and expensive air conditioning and the smell of new carpeting enveloped them as they entered. It reminded Trish of a fancy movie theater. A woman stood behind a long glass counter full of Chinese-language publications. She was stacking what looked like programs for a service, and she greeted them in Chinese, as if casual visitors were not unusual. Hospitably, she waved them towards several sets of large wooden doors on the other side of the lobby.

They pulled open one oversized door and saw a mammoth seating area full of curved pews, a tall, sleek pulpit, and a state-of-the-art digital projector console, with twin screens mounted high on the wall.

"Wow," breathed Pastor Rudy in admiration. Trish guessed he was looking at his dream church. "I wonder if the minister is around. I should have set something up -- but I wasn't sure ... "

He went back to the woman at the counter to make an attempt at communication. He measured off a space next to himself where a person might stand, nodded at it, and joined his hands together piously, then looked at the woman expectantly. Immediately, she made the crisp response that most Yutian people made when confronted with any pathetic request from a foreigner:

"MAYO."

By now the delegates knew this word well, and it was in no way related to a sandwich condiment. It meant, "No, none, nothing, never, forget about it."

"Strange," said Jerome. " You'd think there would be an office somewhere." He looked around at the smooth blank walls.

"My parish practically has me punching a time clock," Rudy said a little sourly. "This guy must be like a civil servant. He probably only has to show up for Sunday mornings and weddings and funerals."

As they made their way back to the entrance, Rudy dawdled at the book counter. Then he stopped.

"These are all Bibles," he said in surprise, looking at the array of books. Some of them were open, showing the Chinese characters and numbered verses.

"Looks like it," said Jerome.

"No, I mean, I thought Bibles were illegal in China. Didn't people used to get arrested for bringing them in? I left mine at home -- Sue was afraid I'd get in trouble. See, look at this."

Rudy was pointing at a sign taped to the top of the glass showcase. It featured urgent red Chinese characters and double exclamation marks.

"Maybe it's some kind of warning," he said. "Like, 'for display only.'"

Jerome studied the sign curiously and then approached the saleswoman. Trish had noted before his uncanny way of getting information out of the Chinese with just the three or four words he'd picked up from Sheldon.

"JIGGA," he said to the woman at the counter, pointing to the sign. "SHUMMA?"

She broke into a torrent of Chinese accompanied by flashing finger gestures, and then she scribbled something on a piece of paper.

Jerome studied it for a moment and then looked at Pastor Rudy, amused. "Don't worry," he said. "They're not illegal. It's a 'buy one, get one free' deal."

"Huh," replied Rudy, sounding almost disappointed.

"I guess the page has turned on that," commented Trish. "Henry did say things are changing fast."

Armed with that bit of enlightenment, they walked back towards the square to start the search for the second church on their list. Jerome had the name of the priest and general directions to St. Joseph's Patriotic Cathedral: "Go north from the square."

"His name is Father Francis Fu," Jerome said, looking at the slip of paper, "and Mei Li said he's been at this church for a long time. The church itself dates back to the missionary days of the early 20th century."

"I wonder how he fared during the Cultural Revolution?" mused Rudy.

"It would be very interesting to know," replied Jerome. "He must have made his peace with the powers that be, if they're letting us see him."

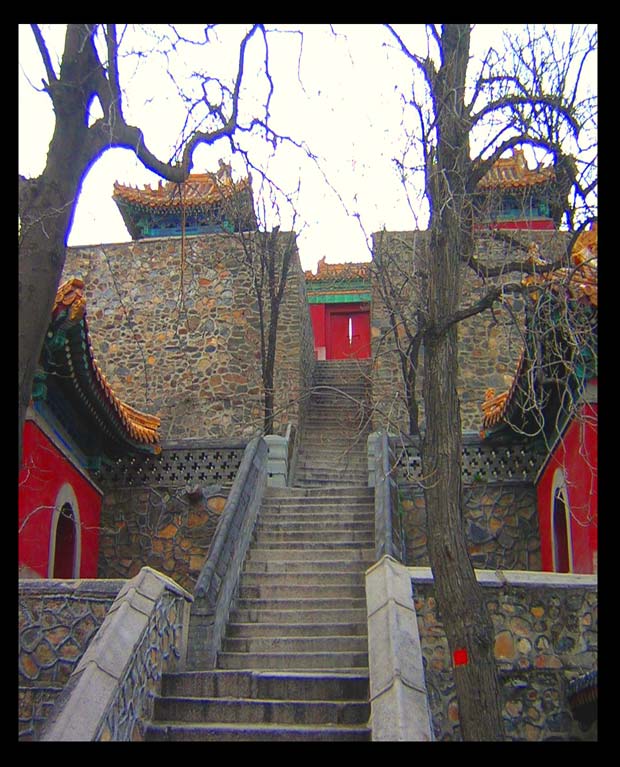

But St. Joseph's wasn't easy to find. It didn't declare itself boldly like the Protestant church. On the map, the dot that marked the church floated in the middle of a city block. It didn't appear to be directly on any street, or if it was, the street was too small to be shown. To complicate matters further, this part of the city was a mixture of decaying old buildings and new construction projects, and many of the streets ended abruptly at a chain link fence or a pile of sand.

Finally Jerome spotted the tips of two startlingly familiar-looking spires just poking through the tops of some tall poplar trees. By following a very unpromising-looking alleyway, full of discarded furniture and other refuse sitting in puddles of water, they discovered the entrance to the narrow garden where the church stood.

"It's like trying to get to Sleeping Beauty's castle," said Trish as they pushed their way past a pile of bricks and some heavy shrubbery. At last they reached an iron gate propped open with a cement block. Beyond the gateway they could see the façade of the church.

Yutian's cathedral was a smaller version of many older North American Catholic churches, with its two modest spires and pretty carved-stone trim around the windows and doors. The stonework was set off from the gray granite walls by a coat of fresh white paint.

"It looks like a fancy cake," observed Trish, enjoying the unexpected sight.

"It reminds me of the old Polish churches in Buffalo," said Jerome. "In fact, it might have been built at the same time."

They tried the big main door. It was firmly locked.

"Someone has to be around," said Trish, spotting some garden tools, a hose, and a half-weeded plot of summer roses. "It has a lived-in look."

"It does," agreed Jerome, looking around appreciatively. Trish guessed he was comparing it favorably with the spare, God-box style of the other church they had just visited. "Let's look around back," Jerome suggested, as if he felt himself to be on home turf. "There should be another door."

There was indeed a small back door to the church, and it was slightly ajar. Tentatively, they entered. Trish was hit at once by a waft of scents from long ago: candle wax and furniture polish, with an undertone of mustiness and incense. Catholicism. It brought with it a rush of anxiety, guilt, and spiritual homesickness, all mixed together. She nearly forgot where on earth she was, literally. It was a little disconcerting.

The church was dim inside, but in the light from a few high, plain windows (there was hardly any stained glass, Trish noted, except for a small window over the altar), she could see all the ecclesiastical details clearly, and it struck her as oddly cozy, for such a tall space. The walls had been decorated from the floor to the top of the arched ceiling -- who knew how? -- with a stenciled pattern of crisscrosses and simple flowers. A miscellaneous collection of brightly-colored saints' statues lined the two long walls, and there were also flickering banks of candles, a super-abundance of plastic flowers, crisply starched linens on the altar, and stacks of missals, hymn books, brochures and prayer cards piled at the ends of the wooden pews.

It all spoke to Trish of an army of middle-aged women who kept the place going -- or that was what she would have thought if she had been in Wheat City. Was it possible that middle-aged Chinese Catholic women could be that similar to Faye Stopanski, Will's mother? she wondered.

"There doesn't seem to be an office here either," Trish said, looking around. "Just like the other one."

"There was a little building out back," recalled Jerome. "In the garden."

And there they found Father Francis Fu, in a lean-to-like building with a tiled roof. He was seated at a desk in a room that Trish suspected might also be his bedroom. There was a single bed against the far wall, with a thin quilt spread on top and an old pair of cloth slippers on the floor below. Or maybe it was just a place for resting. Father Fu appeared to be very elderly and frail, although he held himself quite straight in his desk chair. He grasped at the arm of the chair, wanting to stand to welcome them, and with the other hand he fumbled at a cane that leaned against the desk.

"Please don't disturb yourself, Father," Jerome said immediately, and pulled up the two chairs and a stool that Father Fu indicated as he eased himself back into his chair.

The priest was surely old, but he had keen eyes, Trish noted as he looked them over.

"This is a treat," he stated, smiling, in barely-accented English. "I always enjoy foreign visitors, although not many come to Yutian."

"We're lucky to have found you in," said Jerome, choosing the stool for himself in polite deference to Trish's womanhood and Rudy's long legs.

"They phoned me this morning," the priest informed him with a dry little smile that added to the creases of his deeply lined face. The tip of his chin winked with stubbly white whiskers.

"Oh. Of course," Jerome replied quickly, remembering that this visit had been officially arranged. If Mike were here, Trish thought, he'd be watching to see if they'd been tailed.

Jerome introduced the three of them and began to explain the Yutian-Wheat City twin cities agreement, their interest in the state of religious worship in China generally, and more specifically in the possibility of contacts between churches in the two cities.

Father Fu listened with interest. Meanwhile, Trish, always curious, took in the details of the priest's office. On the wall over the desk hung a large black crucifix, which was to be expected, but under it were two framed black and white photographs, one of Sun Yatsen and one of Zhou Enlai. Trish recognized the iconic faces by now. But she thought it was strange there was no picture of Chairman Mao. They'd seen his likeness everywhere else, more than the other two. On a shelf, a postcard leaned against a row of books, showing mountains and valleys, and with the English words "Sichuan: Land of Abundance" and a small picture of a smiling, gnome-like Deng Xiaoping floating in the sky in the upper right-hand corner. And looking a little out of place directly in front of the work area of the priest's desk, where one might have expected a portrait of the Pope or a statue of the Virgin, sat a brightly-colored stuffed toy, one of the mascots for the upcoming Beijing Olympic Games. Fuwa, Trish knew they were called. She was thinking of getting one for Vanessa. This was the red one whose hat was the Olympic flame, and in one hand it held a little flag with the motto "One World, One Dream."

"Of course," Father Fu was saying to Jerome. "Exchanges are always a very good thing. I once went to America when I was a young man, to New York City. I saw Saint Patrick's Cathedral, and the Empire State Building when it was new! It's important to have such contacts, to build understanding and widen one's view," he said, nodding.

"Speaking of the importance of contacts -- " Jerome leaned forward on his stool and launched the question that really interested him. "I'd like to understand more about your Chinese Catholic Church," he said carefully. "I'm curious -- why do you accept remaining outside the worldwide Catholic Church? Don't you feel ... " And he left it there, waiting to find out what Father Fu did feel.

The old priest leaned back in his chair and rested one foot on a tiny wooden stool nearby. "Foreigners always get things backwards," he said with a shake of his head, but the kindly smile was still there. "It's the Vatican that refuses to recognize our bishops. They don't want us -- they seem to think we are godless communists." He shrugged humorously and spread his hands to indicate, ironically, his office, his church. "They are playing a political game when they should be above politics -- it's that simple. And so they have a very warm relationship with the Church in Taiwan, to make us feel like outcasts. But some day Taiwan will be part of China, in one form or another, and then there will have to be some fancy footwork, as we used to say in my youth. Things will always change, and change in the strangest ways. That's the biggest thing you learn after ninety years!"

Father Fu leaned on his cane and shifted his right leg again, and there was a tightness in his jaw as he moved. Trish had associated the cane with age. Now she realized he had a disability, or perhaps an injury, maybe from the "time of turmoil," as Mei Li called it.

"What Rome -- and others -- would like," he continued, "is for us to turn against our government. But we are Chinese -- haven't they noticed? And do I look like a revolutionary? I am a simple priest. And my parishioners are not revolutionaries either, they only want to practice their faith. And incidentally, there are more parishioners these days than ever before.

"You'll also note that Rome does not ask other countries to do that, to disavow their government before they can have bishops. The United States, for instance -- and I can say this because you are Canadians, that's a nice change -- does His Holiness demand the Americans disavow their government because it invades and destroys other countries and then calls the people they conquer 'terrorists' for defending their land? No, he does not, although he should. Instead, the Pope goes for lunch at the White House. I call this strange. And most Chinese Catholics call this strange. This is why we prefer our Chinese Catholic Church. It's not a bad thing, being patriotic, if you are not a blind patriot. Faith cannot flourish without roots, and our roots are Chinese, very old roots, too."

"But your government," ventured Pastor Rudy. "They've made some bad decisions, don't you think? The Cultural Revolution? Tiananmen in '89?"

Trish hardly dared to breathe. Mei Li would have a fit if she could hear all this.

"How can you--?" Rudy plunged on, but the priest interrupted him, unfazed.

"Of course," agreed Father Fu. "What government hasn't made bad decisions? Just look at the Middle East, the Holy Land! So many bad decisions over the years you can't count them. Mao's Red Guards broke my leg in four places in 1968. I surely believe that was a bad decision. Mao went crazy the way many leaders do, and a whole generation went crazy with him. They were children, mostly. 'Kids,' as you call them. Crazy kids smashed my leg. That's why I had to forgive them -- they were just ignorant kids. They destroyed everything in the church that we weren't able to hide, and they turned the building into a foundry. And some of those people are still among us, right here in Yutian. They are about your age, now -- " He nodded at Jerome and Rudy. "Some of them are even officials."

Officials? thought Trish. Those smiling guys at the dinner with the lacquered pompadours and vinyl comb-overs?

"Like so many people," he went on, "they have conveniently forgotten what they did, and they have gone on to other things. I haven't forgotten, but because I am a Christian I have forgiven. If we don't forgive, we will live with a hard place in our hearts. Yet I insist on remembering, as well as forgiving, because it is important to remember. That is the only way we grow wiser, and live better."

"May I ask -- if the Holy Father were to come to China, would you want to meet with him?" Jerome persisted. "Would that be important to you?"

"Of course. Even though -- or maybe exactly because -- he refuses to approve our bishops, I wish he would come to China. To see for himself. That always makes a huge difference, as you may be learning." Father Fu paused, and his eyes twinkled again. "But I wouldn't talk politics with him. He has certain preconceptions, the kind that are very hard to let go of. Like many others, he needs to see more, and to understand how the present government has as its priority the feeding and clothing and well-being of more than a billion people -- a truly Christian task. And China is not invading other countries, starting wars left and right. Of that Our Lord Jesus Christ would surely approve."

"But -- " Pastor Rudy searched for words. "Don't you feel as if your freedom is curtailed, by the government having a hand in everything?"

The priest smiled. "If you had a billion and more people to care for, you would have a hand in everything too. Think about it." He looked at Rudy. "How many children do you have?"

The minister was caught by surprise. "Children? Me? Ah -- I have two girls."

"Well, if you had ten," Father Fu replied, "you would have a few more rules in your house, I'm sure?"

"I guess -- "

"And my freedom?" Father Fu asked. "What more could I want to do?" He spread out his hands. "I have my living, my parishioners, my garden," he said, pointing across the yard toward the church with one hand. "I even have the internet." He gave a short laugh and pointed with the other hand to something Trish hadn't noticed in her survey of the room, a boxy computer monitor on a table in the corner, protected from dust by a flowered cloth.

"I can't complain. That's a saying you have, but I mean it sincerely. I have seen so much in ninety years, it's been beyond my expectation. I was born a little after the founding of the Republic, in a village not far from here. You cannot imagine how Yutian has changed. Literally, there is no way you can imagine what I have seen. And today -- " His eyes searched the room and fell on the little plush mascot on his desk. "Today I see this. The children gave it to me, to celebrate the Olympics. This is amazing. The whole world is coming to China -- much good will come from that. And you people, you have come all the way from Canada to Yutian, and here we sit talking. I call that wonderful. I am sure Our Lord will bless you for coming."

And then he surprised them by suddenly reaching forward with his right hand and making the sign of the cross in front of each of them.

But the elderly priest was beginning to look a little weary. After Jerome jotted down the mass times at St. Joseph's for future reference, all four of them exchanged good wishes and e-mail addresses, and they left Father Fu where they'd found him, at his desk, as he examined the gifts that Jerome had thought to bring for him, a map of Canada and a small book on the history of Wheat City's Diocese of the Plains.

As they passed out through the rusty church gate, Trish ventured a neutral observation. "Well. That was interesting."

Rudy agreed, then added with a frown, "But it wasn't quite what I was expecting. I thought it would be more like, you know, visiting someone in prison." They picked their way back through the crowded alley towards the street. Then Rudy said, "A penny for your thoughts, Jerome."

They came out onto the main street. Jerome stopped at the curb, blinking in the bright sunlight, and looked up and down the street, as if trying to remember which way they'd come. Then he replied, "Actually, I feel like I've had my head turned inside out."

Trish laughed. "That's what Sheldon calls 'the China syndrome.' "

"But it's not a bad feeling," Jerome added.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.