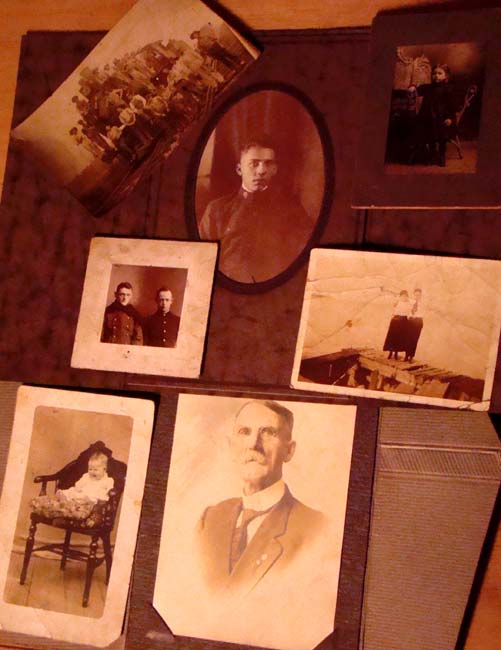

I had taken advantage of a cool rainy morning to do some long overdue tidying in the attic. Too many things had just been dumped up there to get them out of the way, and it was time to sort things out, or at least, that was the intent. Unfortunately, one of the very first things I picked up was a box that contained all the old photos that I had spirited out of my parents' house. It was a collection that dated back many, many years. I had been through this box as a child, and the photos were old then, and they had always held a fascination for me. There were people and places I never knew except from the photos. My grandmothers, for example. I never knew either one. My father's mother had died several years before I was born, and my mother's mother died very shortly after I was born. There were pictures of each, however, and I could imagine them. In one photo in fact, my maternal grandmother held me in her arms. It was the week after I was born, and the month before she died.

Just as I had as a child, I found myself drawn into the box of photos, unable to resist rooting through them and remembering. The pictures of my brother's wedding -- I was six, and the very handsome little ring bearer. We all looked happy in the photos, oblivious to the rancor that would follow in the years leading up to their divorce. There was a picture of my uncle Billy and his brand new 1964 Mustang, the one in which he died, a fiery accident on his way to work. For maybe an hour, I simply sat on the attic floor and pulled out picture after picture and let the memories wash over me.

I had not anticipated that this walk down memory lane would throw light into so many long darkened alleys in my mind. Maybe that's why I kept this box in the attic, and why I have never really talked much about my past with anyone other than my current wife. One of the things that brought us together was a perception that we had some distinctly similar experiences growing up. Our mothers were both controversial, each in their own way, each for their own reasons. I judge that they were nothing alike, but I am not always a good judge in these cases. There can be no denying that for each of us, our mothers' erratic, even neurotic, behavior was formative, and in each other, we recognized the scars and found a companion with whom to heal.

That sounds so terribly dramatic, and if I was indeed on the psychoanalyst's couch, he or she would be pursing his or her lips and hemming. "Tell me more about your relationship with your mother," the analyst would say, and then prepare to take copious notes.

The next photograph out of the box was one of my parents. They are kneeling on opposite sides of their bed, Dad on the left, Mom on the right, and they have joined hands in the middle of the bed. It is a holiday-themed picture. There is a bed spread with large squares filled with Christmas images: a sleigh, a poinsettia, candy canes, Christmas trees, candles and snowmen. Mom is wearing a similarly themed sweater, one she has worn every Christmas season for the past twenty years. Dad has a genuinely happy expression on his face, while Mom has the disingenuous expression that looks a bit like the Mona Lisa, except that her eyes are not focused. It is the expression she had in every photo ever taken of her. I know that she did not like having her picture taken, but I could not tell if that reluctance had to do with vanity or a philosophical dislike of photography. She was not of the "cameras steal the spirit" ilk, but she definitely reacted poorly to the prospect of being photographed, and then later to the photograph itself. That disdain was evident in the expression she wore. I always found it odd that she managed to recreate the damn expression every time.

She wrote on the back of this photograph, explaining that the bedspread was purchased at Mervyn's Department Store, and she lamented that nobody ever got to see it. There were apparently matching sheets.

"Dad is as handsome as ever," she wrote, yet I know that she could not stand the man to whom she was married. She told me that herself, and told my brother John, too. My brother Mark has never said if Mother told him the same as well, but then Mark and I have not had a lot of conversations over the years. The other person of significance that my mother had confided the matter to was Dad. To be perfectly accurate here, she did not, in my hearing at least, tell Dad that she could not stand him, but she adamantly told him that she did not love him any more. For a couple that had been together for thirty years, that would have to have been a disconcerting statement.

Mom and Dad were people whom I respected. I was not, nor am I now, someone who takes to adolescent rants about not being understood. My relationship with my mother and father had little to do with me. I realize that sounds odd if not completely stupid, but I never really had a problem with them as my parents, or with their authority. I accepted the rules of their home because it was their home, and I knew that in the fullness of time I would be in a position to move out and reorder the world to my liking. That seemed an equitable arrangement. Where the relationship with my parents suffered was where in fact all of their relationships suffered -- there was a perpetual state of war between them, and everything about them faced the constant threat of becoming collateral damage.

I do not know when or why the war began. They had been at least infatuated enough with each other to have chosen to marry. Every indication was that it was both a free and a mutual choice. My mother would not have been railroaded into a marriage. She herself would have not considered it, nor would her mother have allowed it. Grandmother Anderson was sensitive on that subject, having herself been given in marriage when she was fourteen to a man thirty years her senior. She ran away from him once, and her own mother beat her and sent her back. That was indeed another time and another world, but the Anderson women would not be coerced again. No, when my mother married, she would have done so freely. Nor was my father my mother's only suitor. If my mother is to be believed, she was in fact weary of all the attention, never lacking for a date. She had discriminating tastes, however, and found all the suitors lacking. There was never any mention of a lost love or even a fondly remembered friend. My mother was looking for a husband, not a good time.

The two met at a church dance. She "knew of him," my mother would say. Typically, she never let on to me at least whether what she knew of him was good or bad. By all accounts, Dad was a dutiful son, a good student, a gentleman; conscientious, trustworthy, responsible, smart, athletic, tall, dark and handsome. The oldest picture I know of my father is their wedding portrait. In that photo, Dad looks remarkably like Gene Kelly.

Maybe it was purely a physical thing; maybe they saw each other and nothing else would do but that they end up in each other's arms, and when the hormones settled down, they were left with irreconcilable differences. I have known people like that. I have also known people so infatuated with the idea of getting married that they never thought through exactly who they were marrying. Either way, waking up after the party can be a sobering experience. It seems unlikely to me that this was my parent's case. They were both cautious and calculating in life. Never in the time I knew them did they ever do anything that could be considered rash or impetuous.

It may have been some damaging indiscretion. Could it be that Dad had an affair, or if not an affair, a relationship that strained the marriage? Mom was a very suspicious and jealous woman. I never saw any basis for mistrust, but I wasn't around for twenty years when Dad was young, when he had two kids and a wife that was difficult to live with. Maybe in the past, there was somebody. Again, it just doesn't seem likely. There was not the slightest hint in Dad's behavior that he had any interest in any woman other than his wife. That includes the years when she made him miserable, when she was thoroughly intolerable to live with, when if Dad had found comfort elsewhere, I might not have blamed him. But the indiscretion might not have been his. There had been a war on, and although Dad did not serve overseas, he did his time in the defense industry, working long hours, six and seven days a week. Mom was young then. Maybe she found something she needed when Dad was at work, and unable to handle the guilt, she tried to transfer blame by demonizing her husband, creating the conditions that could justify her actions. Could happen, it is a common psychological trick people play on themselves. But once again, it just doesn't seem likely. Mom was too sexually repressed to have considered anything that would require spontaneous sensuality, and she was generally too condemnatory of men to have sought male companionship. A lesbian relationship could be a possibility, but I do not believe lesbianism had been invented in that part of the country at that time, and Mom could never even say the word lesbian without spitting and shivering in disgust.

Voluntary dalliance seemed totally incongruent for either parent actually, but maybe it was not voluntary. With Mom, I have never been able to rule out the possibility that she had been abused, perhaps sexually abused, perhaps by somebody close. There are women who don't like sex, and consider it tedious, or even disgusting, but Mom's antipathy went much deeper and seemed much darker. She was uncomfortable talking about sex, which again is not uncommon, but when she did talk about sex, there was an unmistakable anger in her voice and in her eyes. Maybe sharing a bed with a man she did not like made her bitter, or maybe sharing a bed at all was more than she could endure. If she had been abused, the process of coping with that would have required an unusual sensitivity on the part of my father, and that particular type of sensitivity would have been the one quality the otherwise conscientious, trustworthy, responsible, smart, athletic, tall, dark and handsome gentleman did not have.

Dad did not have the particular quality that was needed to deal with my mother's peculiarities. I wish I could say that is simply another way of saying oil and water don't mix, but unfortunately in this case, a more apt analogy would be to say that matter and anti-matter tend to irritate each other.

Dad was a positive person. It was the kind of positivism that is born on the field of play. Winning is about being positive, believing in the abilities of the individual and the team to be able to overcome any obstacle thrown up by the opposition. My father understood my mother's brokenness as a competitive challenge, something to be defeated. This is what he was good at, the way he saw the world.

My mother resented any thought of being fixed, in large part because she never saw herself as in any way broken. Wounded? Perhaps. Cheated? Possibly. Misunderstood?

Very definitely. She had a clear view of the world, and in that world she was intelligent, clever, creative, and of course very, very wise. In the real world she may have been these things, if not always at least occasionally. In her world, she was also humble and patient, but in the real world she was neither. She was a very vain woman who insisted that all things be ordered to her liking, and when things were not immediately so, she was by turn angry and depressed. She wanted to be loved, but by that she meant to be obeyed and admired, and when she was not, she was by turn angry and depressed. She wanted to be happy, by which she meant that she achieved what she wanted, but when she succeeded, she only felt hollow, for possessing any one thing only brought into sharp relief how many more things she lacked. When she realized that happiness was not where she thought it might be, she was by turn angry and depressed.

So while my mother bled her anger all over their lives, Dad kept dribbling around it and playing the wrong game. There was never any resolution to any of the arguments, and in fact resolution was not even considered an option. Any topic could be used as an excuse to land a few blows. The age of relatives or friends was a frequent trigger for an argument. A simple statement about someone being in their forties, or Dick being older than Jane, or so-and-so being born in 1941 would trigger a knock-down-drag-out affair that could last for hours. Facts meant nothing in these instances as neither party was willing to look anything up or give anyone a call to settle the matter. The argument would continue even if nobody else in the room cared about the outcome. And the argument never stayed on task. It may have started over the question of a birthday, but soon incidents that occurred twenty years ago were resurrected; questions of how much the members of one's family drank became germane; damning evidence of conceit and deception, long held secret at terrible personal cost, now spilled onto the table. It was like a bar fight that starts with a few shoves, but then all the tables and mirrors get broken before tangled bodies burst out through the windows and tumble onto the street.

"So, Mr. Smith," my analyst says letting the cramp in his writing hand ease. "How do you feel about your mother?"

I have already said more than I wanted, Doc. I used to try to get my parents to just drop the old subjects, the stuff that had occurred thirty years ago, the things that had no relevance any more. Dad is dead. Mom is so old now that there is little reason to believe that she will change. She is locked so deeply into the anger and arguments that it is hard to tell if anything she says has any basis in reality. She is unopposed now, and I would have thought that that alone would have mellowed her, but it hasn't.

I know how much of my behavior is a result of having lived in that environment. I am antisocial, and I am content to be cloistered in my home. Conflict is physically uncomfortable for me, and perhaps I compromise too much to avoid conflict. It makes me wonder if I might be right that there was some abuse in my mother's past that scarred her.

Maybe she had a box of old photographs that she used to go through. Maybe it got to her. Maybe she was haunted by her history. I can understand that.

"Hey." My wife's voice. In my reverie I hadn't noticed her coming up the stairs. "There you are. I've been looking all over for you. What are you up to?"

"Visiting my family."

"Ah. You found that old box of pictures."

"Yeah."

"Want some company?"

"Sure."

"So, how is everyone doing?"

"Remarkably nobody has aged a bit," I said.

Sarah smiled and sat down cross-legged on the floor.

"Here," I said and handed her a picture. "This is the last photo my parents took of me." I was nine years old, and I was standing at the altar rail of Immaculate Conception Church with a priest. I was dressed in a blue suit that I remembered as being very itchy. I had just received First Communion. "It was taken with an old Argus box camera, the kind that you opened the flap on top and looked down through the view finder, and it used those rolls of film that you had to thread into the camera and then crank away until the little number appeared in the red window on the back of the camera."

"I remember those," Sarah said. "Dad had something like that, except it had a strap on the top."

"A Brownie."

"A brownie?"

"A Kodak Brownie. Same idea, a simple box camera, just Kodak's version."

"Dad never really let me use the old camera, too concerned with me handling the film, although he did eventually let me have an Instamatic, the one that used the film cartridges."

"Ah, the relentless march of technology making our lives ever better."

"So why is that the last picture they took of you?"

"The Argus broke."

A lot of things broke in and around the time of First Communion. The arguing grew more frequent and more bitter. We stopped visiting family except at funerals. We stopped going to church. We never replaced the camera.

"I think," I said, "that things began to change too quickly for Dad. He liked rules. He liked continuity. He believed that if you worked hard and lived honestly, you would live happily ever after, but it just didn't work out that way."

Sarah nodded slowly as if in sympathy, but she seemed more occupied with examining the figure of the boy in the photograph, the one who would someday be her husband. It would not have been the first time she had heard me try to explain what it was like in my family. We had often compared notes, often repeated the stories of our past. It helped us understand our own limitations.

"Did you believe in God then?" Sarah asked.

"When?"

"In this picture. Is this what it looks like to believe in God?"

"To be honest, I don't remember what I believed just then. I don't know that I believed anything. It's not really a fair question for someone that age."

"Yet there you are -- you've got the suit on and you're smiling."

"Yeah, well, you can always play the part, you know?"

"So how old do you have to be to make up your mind about God?"

God was not a topic that Sarah and I had spent much time on. The morning after the first night she had spent in my apartment was a Sunday. I knew her name, that she was divorced or at least going through a divorce, and was very fond of margaritas, jazz and Golden Age science fiction, all three of which I had in abundance in my apartment.

"I could take you home," I had said when she awakened.

"Or?"

"I could take you to breakfast."

"Possibly."

"Or," and here I asked tentatively and only to be polite, "I could take you to your church."

"Don't have one, don't need one. What happens after breakfast?"

"I like to spend the day in bed."

"All day?"

"Well, there is the issue of lunch and dinner, but otherwise ..."

It was the only conversation we had about religion before we were married. It had seemed sufficient at the time.

"I don't know how old you have to be to make a call on the God issue," I said. "How old do you have to be to get married?"

"Forty," Sarah said.

"You were thirty-five when you married me."

"It was a mistake." She repressed a smile, but only barely.

"Seriously, how old do you have to be to make an informed choice about getting married?"

"Depends."

"On what?"

"On the individual."

"You were twenty-three when you first got married," I said. "Was that old enough?"

"For me, yes, but Dickhead was twenty-eight, and as it turned out, didn't have a clue."

"And despite that fact that I am exactly twice as old as Dickhead was when you married him, how do you know that I am not a dickhead?"

"I don't," Sarah said far too quickly. The satisfaction, of what the moment before had seemed like a positive movement in the direction of understanding a fundamental aspect of the human condition, was tempered by the fact that I had achieved this small success by having maneuvered my wife into revealing that despite twenty years of marriage, I had not given her enough reason to trust me. The galling reality was that she was not only right, but justified. We had entered into marriage as older, wiser, less naive individuals. In the vows we exchanged, we had purposely left out any of the "until death do us part" sentiments. It was to be for as long as we each found it ... good.

Early on in the marriage, it was this sense of freedom and daring that added a spark to the relationship. Every day it was a choice, something that had seemed oppressively absent from my first marriage, where I had inadvertently married my mother. My ex was person of implacable needs, not the least of which was her need to remake me in her image. She was intent on draining every bit of color from my life and replacing it with a sepia caricature. She was not, I think, unique. There are always difficult individuals to deal with in life, but when dealing with them, the irritation is mitigated by the comfort of knowing that at the end of the day they will go home, and if necessary, they can be avoided. In marriage however, there is the miasma of permanence, an institutional imperative that crushes self-preservation, and so there is a picture somewhere I'm sure of me standing next to my ex, smiling, dressed a blue suit that I remember as being very itchy.

In the one unselfish act of her life, my first wife died and is therefore, for the most part, irrevocably removed from my life. Sarah's ex has not been so obliging. He will from time to time find us and try to hit Sarah up for money. He is an indigent with alcohol and gambling addictions that had ruined every relationship in his life.

"It's been twenty years," I said.

"And it's still good," Sarah said with a gentle, apologetic smile.

"Good enough?"

"No, good."

"Good enough," I said.

"Is it? Is it good enough for you?"

Maybe it's my age that makes me want more. I want assurances now, I want control. I want the hope that comes from having a founded expectation that it will be okay to get old, that there will be someone there who knows where I've been, what I have done, what I have failed to do, and still freely chooses to smile and be kind. It's not been my experience though. There are no guarantees. Every day that I wake up, it's a choice to recreate what I had yesterday. As strongly as I feel about Sarah, as much as I want her in my life, I just can't be sure that there's not going to be some set of circumstances which I will choose to walk away from. I won't live like my parents, the life being sucked out of me by some delusional belief in a fanciful absolutism that "love conquers all."

"Here," I said and tossed a handful of photos on floor between us. "Look at these and tell me what they all have in common."

"I give," Sarah said. She never had much patience with riddles.

"None of the people in these pictures knew what they were doing, not really. They were bouncing around from disaster to disaster hoping that things wouldn't get worse."

"That's pretty negative."

"Is it?" I grabbed one of the pictures off the floor. "Here. This is my Aunt Helen. She left her husband for a guy that promised to build her a house on the Jersey Shore. She died broke and alone in Hoboken. Or this one. This is the kid who used to live next door to my parents' house. Last I heard, he had been married six times, and all six were savage affairs."

"Shit happens," Sarah said. "Everybody knows that."

"That's pretty negative, isn't it?"

"No, it's just the way it is. Nobody's perfect."

"So they say."

"So what are you saying? Are you worried that I am going to betray you?"

"No," I said softly. I looked into Sarah's eyes only long enough to let her know I was sincere, and I was, but it was the answer I would have given under any circumstance in order to change the direction of the conversation. I did not want to go too far down the path of measuring the commitment we each had for our relationship. I would want Sarah to say that she was bound to me for life, but the reality was that in my mind, this was less a covenant as it was a deed. I wanted the security of a sealed document conveying to me the ownership of her affections, but I was unwilling to barter away my future on vagaries. Maybe that's a weakness. Maybe that's just how it is. In any case, if I am honest with myself about myself, I have to allow that for Sarah, there is more than enough reason to be cautious. The price of peace is eternal vigilance, eh?

I took a deep breath and exhaled deliberately and long. "What we have is good." I glanced quickly from the floor to her eyes and then back to the floor. "There's a picture that's not in the box. It's one that's in my head. It's of Dad sitting on the front porch steps crying. He was older then, already retired. They had been arguing, as usual. Dad had been trying to explain to me his side of the argument, but then he just stopped. Maybe he realized that I had heard it all before, but whatever, he just stopped, looked at me plaintively and said, 'If I had known it would turn out like this,' and then just sobbed."

"He was a good man," Sarah offered.

"I don't know. Maybe. Maybe not. Not everybody who dies in a war is a hero."

"I won't do that to you."

"I know," I lied.

The sins of the fathers will be visited on the children to the third and fourth generation, or so I have been told -- sounds plausible when I think about it. My box of photographs gives me little to be encouraged about. We have no children, Sarah and I, so at least it ends with us. If we muddle it all, at least there's no next generation to catch hell for what we've done.

"Good," I said to Sarah.

"What?"

"You wanted to know if I believed in God in that picture."

"And?"

"I remember believing in a permanent good, the idea that no matter how broken things were, there was something that could fix them, and that it would always be there."

"A childish fantasy."

"Or an old man's hope."

"You're not going to get all superstitious on me, are you?"

"No," I lied. I needed a god in my life, but I doubted that I could promise that god any more than I could promise Sarah, or that I could trust that god any more than I could trust Sarah.

"We'll be okay," Sarah said.

"I know," I lied once again. It was all I could think to do.

03/19/2013

05:34:34 PM