As I walked through the trees, the smell of smoke became stronger and stronger, and the thin wisps drifting into the forest, slithering over the leaves and branches, became thicker, until the whole wood was covered in a grey fog. I fumbled my way along, hearing the leaves beneath my boots crunching as I trod on them, and occasionally, when the piles became too thick, I would kick them away, and it would sound like whispers were filling up the forest.

A little further on I began to hear sounds. Horses could be heard whinnying over the low hum of human voices, and then shrieks and wails would puncture the air, though whether human or animal I could not tell. I reached down for the sword hilt, feeling my unseen fingers tightening around it. I wondered if there were others in the forest with me, roaming about. It did not seem possible that others would not think to take shelter in here given what had just happened.

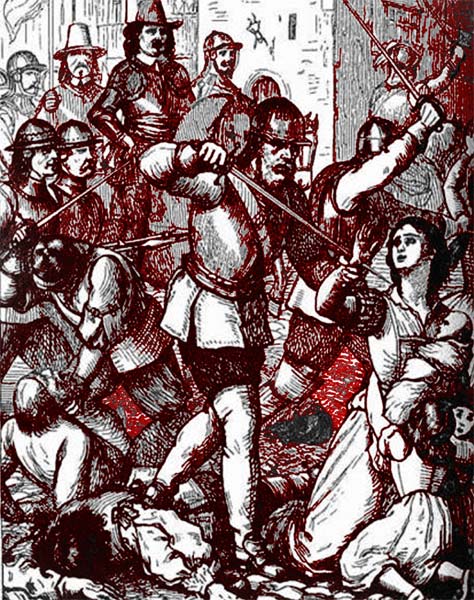

I could just about see the field ahead. Dark figures obscured by the mist were milling about. Some were reaching down, others seemed like dancing shadows, and I realised they were trying to stop a horse from running away. The closer I got, the more people I could see, like a picture gradually being filled in with colour and detail. But some details are best remained covered. As I emerged from the forest, I could see the damage the battle had wreaked on the land and the people who fought in it.

I made the sign of the cross. For the dead of both sides. I had no one to follow in this war, and I helped whoever I could. Huge piles of bodies lay like mounds of earth churned up, blood-streaked and limp, their eyes sightless and grey, staring up at a sky they could not see. Others lay, twitching and shivering in the chill of the autumn air. None of them would ever get up again, and I could not help them. The fools tried. They picked up their fallen friends and carried them away from the field. I walked and walked, but could not find anyone who could be helped. I noticed a soldier slumped over a cannon from which smoke was billowing. His back heaved, his shoulders rising and falling quicker than a heartbeat, his battledress torn, charred black, the fabric crisp. Through the tear in his uniform I could see that his skin was a mangled, burnt mess. I took hold of him and pulled him gently off the cannon, seeing that it was drenched in blood, and then I saw the wound in his stomach, and knew it was not worth trying. The man looked into my eyes, his pupils wide, and for a moment I thought he looked crazed. Then his breaths became even shorter, and the rasps that emanated from his bloody mouth began to sound like howling wind. I lowered him onto the field, closed his eyes and walked away.

There was not much grass left underfoot. I tramped through mud, my feet slipping and sliding, until my trousers were spattered in dozens of tiny brown dots. A man to the right of me cursed as he fell over, coating his uniform in dirt and grime. He dragged himself to his feet, and spat on the ground.

"Doctor! Over here! Now!"

I turned to the sound of the voice. It was coming from a man who stood in the middle of a circle of bodies. I walked towards him, stepping over the dead.

"Can I help you, sir?" I asked him.

"Are you for the King or Parliament?"

"Neither."

His eyes narrowed behind the mask of blood and mud. I looked at his uniform, noticing for the first time its finery. This was a King's man.

"Then you are worse than a traitor."

"Tell, me" I said. "Who is more of a traitor to this land? The man who heals the injured, or the soldier who kills his countrymen?" I fingered the sword again.

He glanced at me, a look of contempt on his face. "I want no help from such as you. Away with you."

"You called me over. I want no quarrel with you or anyone else. What do you need?" I took my hand off my sword, to show him I meant no harm.

He sighed. "I need to find a friend of mine. He fought in this battle."

"What is his name?"

"Thomas Yaxon."

"And who does he fight for?"

"Parliament."

I stared at him, surprised. Perhaps the world is not at an end after all. "How do you know he was here?"

He looked at me and I saw in his eyes that he was afraid. "When the two armies were close together he sent me a letter. We -- we met last night in the woods nearby. He said to find him after the battle, and if he should fall, to bury him."

I tried to calm the man. "I have no part in this war. You need not worry about word of your actions getting back to your commander. How will we find Yaxon?"

"He told me that he would wear a black ribbon on his arm." He touched his arm, and I noticed that he had his own ribbon, although his was yellow.

We began our search. The chances of finding Yaxon were slim. I feared for the state he would be in even if we did find him. If he were alive or unharmed, he would not still be here. "What is your name?" I asked my companion.

"William Newark," he replied. "And yours?"

"Robert. I keep no surname."

"Why?"

"Family is something I wish to forget." Newark had a confused look on his face, but he said no more.

I searched the bodies on the ground for the tell-tale black ribbon. Newark did the same a few yards away. I could hear him cursing as he clambered over the dying. I wondered how used he was to fighting. It was difficult to identify most of the bodies. Some of them had suffered injuries so terrible it was difficult to find the human being underneath, let alone a thin ribbon. I was about to tell Newark we should head to a different area when I noticed a man slumped against a tree. I walked towards him, noticing that his head was moving slightly. Once I was standing over him I noticed to my shock the ribbon around his arm. It was Yaxon. "Newark!" I called out. He came running over. Yaxon was moaning softly. He opened his eyes slowly.

"Will," he groaned. A trickle of blood oozed out of the corner of his mouth. "You survived ... good." He closed his eyes, and a spasm of pain passed over his face. I looked at Yaxon's wounds, and saw that it was too late already. His uniform was soaked in red, and there were several gaping holes in his chest, from which blood was streaming. He tried to raise his hand, but it fell limp at his side. "I'm glad ... you are unhurt, my friend."

I looked at Newark. His eyes looked dead, as if he had had something knocked out of him. "Can you help him?" he whispered to me, though I could see that he already knew.

"No," I said quietly. "His wounds are too numerous. He is in God's hands now."

Newark looked away, back towards Yaxon. "I'm here, Thomas. I'll wait with you."

Yaxon's mouth twisted into a lopsided grin. "You bastard ...You always were lucky. Well, at least you get to go home. That's one thing I won't have to endure." He coughed, and droplets of blood speckled his chin. "What an adventure, eh?"

Newark laughed in spite of himself, but I could hear the laughter begin to crack, and I became aware that he was crying. "I'll let your parents know," he said.

"Thank you, friend. It's a good thing it's you going back, a -- and not me. I never could ... find my way home. I'd have been in Wales before I realised I was going in the wrong direction." He gasped out the last word and his hand clenched around Newark's. The laughter left his eyes. "God forgive me," he rasped. His breaths became shorter and shorter, and he moaned, a high-pitched wine, like the sound of a table screeching on wood. He kicked and jerked, his limbs smacking against the ground, and then lay still. His eyes rolled to one side, staring off at the forest in the distance.

Newark wiped his eyes on his sleeve. He reached out and closed Yaxon's. Then he stood up. "How much do I pay you, physician?"

"Nothing. I have done nothing." The weight of it filled me with misery. I had walked past a thousand of the dying today, and not a single one had I saved.

Newark was silent as he closed his dead friend's eyes. When it was done he asked me to come with him to a nearby inn. He placed his sword against the tree.

"Will you not need it?" I asked him.

"No. I will fight no more battles," he replied.

We rode to the inn. I had kept my own weapons. The roads were not safe these days.

The inn was empty. "I will stay here tonight," said Newark. "You are welcome to join me. Then tomorrow I will be on my way." I nodded. I stared around at the tables. Most of them were covered in dust, and it was impossible to see out of the dirty windows. No one had been here for a long time.

The sun went down. We lit some candles Newark found upstairs. He pulled out a pipe and began to smoke, staring into the candle light. "Was that your first battle?" I asked him.

"No. I fought at Edgehill. The very first. I have killed many men since then. I was once glad to have killed the King's enemies, but now ..." He paused. "I thought I was used to death."

"How long did you know Yaxon?"

"Since we were boys. We grew up together."

"But you ended up as enemies?"

"No. Never enemies. I never hated him. We just took different sides. I thank God we never chanced upon each other in the battle. Though perhaps we would both still be standing if we had."

"Are his parents for Parliament?"

"Yes. I cannot seek them out. I promised Thomas, but they will not hear of his death from me."

"This war has ruined this country." I said. I gazed into the candle flame, watching it flicker in the dark.

"What of you, Robert? Why do you wish to forget your family?"

I did not look at him. "When the war started, we were unsure of who to join. My wife and I just wanted to keep our children safe. But the fighting started to spread, and we resolved to leave our home and head somewhere away from it all. One day, after I had been out, finding supplies for our journey, I came home, and I found them ..."

"What happened to them, Robert?"

"I came home and saw that our house had been broken into. The windows had been shot out, so there was glass everywhere. The door was left ajar. When I went in I saw what they had done to my family. None of them were left alive."

"Who had done this?"

"I never found out. Royalist or Parliamentarian could have done that, and I will not fight for either side."

Newark glanced at the candles. "They will be punished one day, my friend."

"Perhaps. You say you were used to death, once. That was a blessing. I go from field to field, filled with dead, and it has made me cold, Newark. I leave the injured to die. I am a doctor. If I am supposed to save them, then thousands have died because of me. I only save who I can, and those are few. I watch them rise again and they find another battlefield and on it goes. The killing. My work is never done. If this is truly the end of all things, then it is a shameful end. Nobody will ever heal. I know I will not. I long for the day when I can join my family. I wish I had been there with them, either to meet my end or to see the faces that entered our house on that day. Then I would have a purpose. I would not have to clean up the stink of humanity."

Newark looked away. "Where will you go?" I asked him.

"Not home, at least not yet."

"Where is home, for you?"

"Kent. I will go there one day. But I cannot see Thomas's parents."

"I will go," I said suddenly. "I will find them and tell them of their son's death. They will have the truth of it, at least."

Newark looked grateful. Shortly after, we put out the candles. I looked out the door at the road and the darkened trees that surrounded it. When I awoke in the morning, Newark had gone.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.