They were all gone now. As Clyde Snyder locked his office door, he realized he was the last of the old gang. Most simply had grown up. Richards, Schulz, O'Hagen, Connelly, LoPresti, McWilliams, and Porter all were married and had families. O'Neal and Thompson were in jail. Reed and Gustafson were dead. He felt his eyes become damp as he remembered each of those names, and how much he missed them all. How much he missed those old days.

He remembered very well 1919, and the Volstead act going into effect. For the veteran, it was a very jarring "Welcome Home," after spending months slogging through the trenches. Clyde gravitated back to his old neighborhood and his old high school friends. With him was Wilbur Reed, an Arkansas farm boy who had saved his life outside of Mountfaucon, less than a month before the war ended.

Clyde had promised Wilbur a job in his father's brewery. Now the factory doors were all nailed shut. The victory parties were all without the salve that would make remembering the horrors more tolerable. This was supposed to make men more godly. Instead, it made these men, who'd proven their patriotism at places like the Belleau Woods and Argonne Forest, more willing to break this cruel law.

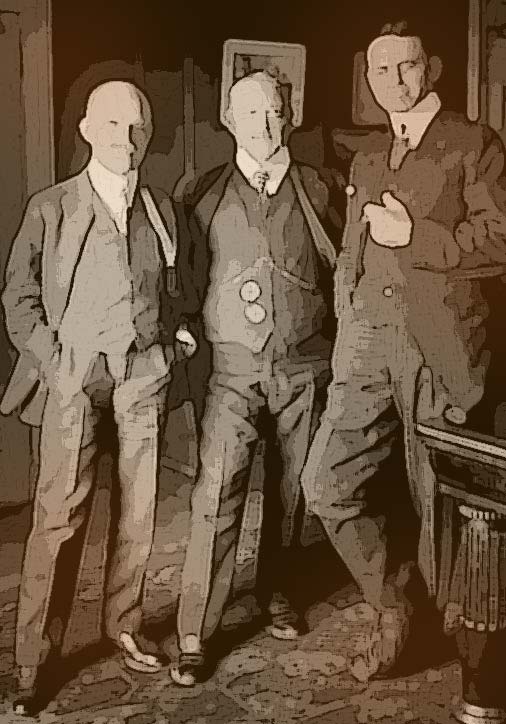

Old Joe Snyder taught his son well. James Richards and Tom Gustafson knew how to buy the ingredients without raising suspicions of law enforcement. Billy O'Hagen and Carl Porter understood the bookkeeping and handling the money. But Clyde was the brewmaster who could put it all together to create a delicious beer. He understood the difference in grains, the use of hops, and the intricacies of the brewing process lost to dabblers in the craft.

A light-textured Bohemian style or a deep, rich ale, Clyde had mastered them all before his induction into the military. Yes, inheriting a brewery might have made him rich. But as soon as the Anti-Saloon League got its way, Clyde realized that selling off the equipment and raw materials would hardly have raised enough money to last very long. And as they were all young, unmarried, and mostly veterans themselves, they did not mind working in a darkened, boarded-up factory in the middle of the night.

A network of contacts provided orders weeks before the first keg was sealed. These would also provide the brewery with whatever it needed -- money, supplies, or on very rare occasions, muscle.

Occasionally a club would get significantly behind on payment. It simply took a few mean glances at a few customers to change that. Only once did they need to resort to violence. A little misplaced trust in a kid who seemed trustworthy. Then a knock on the door, and a shipment was hijacked at gunpoint. There was a greater loss to Clyde though, than the beer. Cindy, the love of his life, left him, having always disapproved of his profession (although having always enjoyed the product), and did not enjoy having guns pointed at her. She left him that night, eventually marrying an insurance salesman.

But things were usually quiet, a steady cycle of fermentation, bottling, and distribution. The money was great, but more it was the camaraderie, a bunch of friends hanging out together, drinking beer, and making a lot of money. Occasionally there were disagreements, but Wilbur Reed, with his sly, yokel sense of humor, was a calming influence, the "Will Rodgers" of the group. Clyde called him on more than once occasion to defuse a quarrel.

People who fall asleep as the first rays of sunlight peer over the horizon can be depended upon to have eccentricities. Billy O'Hagen had a spinet piano next to his desk and marked every 2 am by performing an old Irish dirge. Gino LoPresti kept an almanac with him and each warm morning, would greet the sunrise by walking outside stark naked and say what was apparently a prayer, in Latin. Charley McWilliams would walk to a table in the large shipping dock, now unused, to eat his lunch, feeling that eating in the factory and office were unprofessional. Carl Porter had a fondness for wearing old-fashioned whale-bone corsets. It was funny to most of the workers, but a little disturbing to a few, who found he looked better so attired than most of the women they knew.

So it was a huge surprise to them all when, in 1921, Carl Porter got married and decided to quit the business and sell his share in the company. Then came the resignations of Gino LoPresti and James Richards. Tom Gustafson was killed by a drunk driver while crossing an icy street in 1924. Then there were more marriages and several arrests -- none though who put the brewery at risk, all preferring jail-time to ratting out their friends.

Then came Wilbur Reed, who one night in December 1931, tearfully said that he was dying of cancer. Clyde visited his hospital room every day, and saw the once-burly farm boy slowly shrivel up to an emaciated shell of the man he once been.

Clyde sat alone in his kitchen, a six pack of beer and folded newspaper on his table. The headline was about Germany remilitarizing the Rhineland, with no French or British interference. In the obituaries was the small entry for Wilbur Reed. Only Clyde survived Prohibition alive and unmarried, two things that once meant far more than they now did.

Clyde already had paid for Wilbur to be returned to his hometown in Arkansas. For the plot, and the funeral, as well. He received a long "thank you" letter from Wilbur's parents and the slightly veiled request that he not attend the funeral. Instead, he opened one of the now-legal beers and took a large swig, remembering the old days. "To you," he said, remembering that muddy October day they first met.

His brewery was now simply one of the little local breweries every city seemed to have, and it was consistently in the black. The "pariah" most once would have considered him was now a respectable businessman and sought after by the daughters of some of the town's leading citizens for marriage. He was "legit," but somehow, it wasn't the same.

* * *

Please enjoy Dan Mulhollen's commentary on his writings at Pikers Stories.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.