"World War III ended seconds after it began," Professor Harold Markham, a tall, stout black man in his late forties said, sitting at the head of a small, round table. "True, since the 1980s, every major power, not to mention several minor powers, had developed electromagnetic pulse weapons. By the start of the war, a simple forty-dollar drone with a small EMP device could disable a neighborhood. So after the US and Russia went at it, North and South Korea went at it, Israel and Iran went at it, England and Scotland went at it, the world was left with a lot of expensive paperweights."

"Casualties were light, though," Chief Financial Officer Arlene Chin, a thin Asian woman with bright red streaks in her black hair, stated.

"Mostly fist-fights due to non-functional traffic lights," Professor Markham said with a chuckle. "But Humanity proved itself exceptionally adaptable. Doctors and nurses remembering paper charts worked nearly as well as their computerized counterparts. Obsessive collectors made a sizable profit with old rotary telephones, typewriters, even slide rules in demand. I, myself, made a couple grand on a few old IBM Selectrics and my mother's old Princess telephone."

Chief Engineer Roscoe Barnes, a thin, pale seventy-year-old shook his head. "There was the normal belligerence -- especially among politicians and those already so inclined to hate anyone different from themselves."

"But when both the United States President suggested reinstating the draft," CFO Chin, said, smiling, "and the Russian President suggested reestablishing the USSR and the Soviet Bloc, both were forced into an early retirement."

"I believe," Professor Markham added, "one Russian oligarch quipped, 'Better retirement than the alternative, like with the Romanovs.' But the question facing us now is not can we start making any and all derived technologies again -- we can. Thirty years of relearning all the old techniques, we have transistors and are on the verge of reinventing the integrated circuit. The question is: should we?"

The question was met with confused stares. "Should we? Why not?"

"I'd like to think of the past thirty years as a do-over. Getting a chance to learn from past mistakes. But I'm not so sure we have. There are some advantages to losing solid-state electronics."

"Education has flourished," Roscoe Barnes said, "with so many old ways to re-learn. I remember teaching fifth grade and watching a student looking at a clock for over five minutes unsure of what the big hand and the little hand were saying."

"Colleges replaced useless fill-in-the-blank 'Studies' courses with courses on welding, automatic transmission repair, and plumbing," Markham said, satisfaction in his voice.

"And," CFO Chin stated, "there was a renewed interest in the arts, with students in older high school buildings learning what that mysterious chamber labeled 'darkroom' was all about. I'd been wondering about that one, myself."

"But what about the trains?" Roscoe Barnes asked. "Wasting a couple hours a day commuting?"

"I rather enjoy the solitude," Professor Markham said. "Y'know, I think that's what's wrong with people in the so-called 'Information Age.' People had developed an unnatural need to always be connected."

"And now," Arlene Chin said in a low growl, "there are asylums popping up for people who can't cope with solitude."

"When working on a difficult paper," Professor Markham said, leaning back, his head cradled in his hands, "I always found a long, meditative stroll helpful. Browsing the Web is a poor substitute for time alone with one's thoughts."

"You are of a dying generation," Arlene Chin said, a hint of sadness in her voice. "I spent three weeks in one of those asylums when my parents thought I was suicidal after my cell phone stopped working. Not even close. I always felt an odd nostalgia for the generations before my birth. My upbringing, perhaps, but I could imagine myself working with a ledger book and a large adding machine. Admittedly, the reality was quite different from the romantic view."

"I was never that romantic," Roscoe Barnes said, unable to keep from laughing. "I'm the oldest one here and I needed my cell phone. My computer." He abruptly stopped laughing and shook his head. "I always needed to be connected. I always need my people."

"And how well did you really know any of them?" Professor Markham asked. "Did you ever even meet any of 'your people' on a face-to-face basis?"

"That would be creepy."

"Why?"

"It's scary," Arlene Chin said, "when I think about how much personal information I've given to people I never met. My dreams, my desires, my fantasies ..." her voice trailed off as her expression changed from soft dreaminess to discomfort.

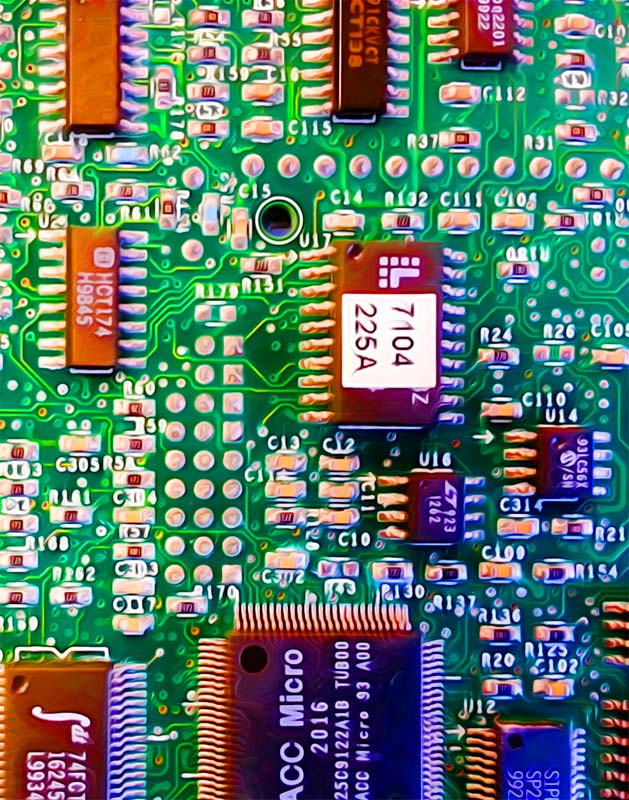

"We now have the technical ability to take a slab of silicon, chemically treat it, and etch in the microscopic circuits so that it can grow up to be a computer. But again, my question to the two of you is should we?"

"It's a break-even thing," Roscoe Barnes said, shaking his head. "We might save a few lives due to instant medical information, but we might lose a few folks due to stalkers."

Professor Markham looked down. "I can remember," he said, his words seemingly painful, "the last few years of the Internet. There was no such thing as privacy. Someone would pick up on your eccentricities and you'd end up getting a dozen emails per day from them, either asking for money to keep quiet or worse, considering you a kindred spirit."

"We've rediscovered the genie in the bottle. But aren't we kidding ourselves? The United States discovered the A Bomb, but Germany could have, had they not pissed off the Russians, British, and Americans. How many laboratories are currently working to reinvent the transistor? One hundred? One thousand?"

"Worldwide," Arlene Chin said, "fifteen thousand four hundred and seventy-five -- as of last Saturday. Many have runners waiting on motor bikes to dash over to the Patent Office to stake their claim. Some lab is going to get very rich. Much sooner rather than later."

"So why not us?" Professor Markham asked in frustration. "I started this company for just this reason. We can send our runner off to the patent office the moment we have a working model and hope he's not a second too late. It's like Napoleon said, 'You can't hold back the tide with your bare hands.'"

"Well, then," Roscoe Barnes said, smiling, "if you can't hold back the tide, isn't it best to learn how to surf?"

"I already know how," Arlene Chin said, a sly grin on her face. "And look damn hot in a bikini."

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.