I'm in Mayaguez, Puerto Rico, at my son and daughter-in-law's winter home. I'm trying, without much success, to adjust the derailleurs on one of the twin's bicycles. The humidity and the heat are taking their toll.

I increase the volume on my portable speaker, and Leadbelly's Bourgeois Blues rings out loud and clear across the patio with the misting system, over the lush lawn and skimming the azure swimming pool.

I sing along. Out of the corner of my eye, I catch sight of the nine-year-old identical twins, Jan and June, creeping up on me. They must be tired of video games or annoying their parents. I'm sure they're out here to ambush me. "What do you two imps want? I hope you're here to help me adjust these derailleurs. I hope the hell that you two are experts on bicycle gears."

June sees that the element of surprise is lost and steps out in front of me while her sister lingers behind thinking of some mischief she can spring on me while I'm concentrating on her twin. I know these creatures well.

June, the distraction, says, "Grampa, who's that? Oh, like, did he just say, the 'N' word? I'm going to tell Dad you're corrupting our tender, young minds."

At that moment Jan leaps to the attack. I slide to the side; she misses and flops on the lounger next to me. I grab her in a headlock.

Jan squeals in anger and frustration and claws at my arms and tries to knee me in the back. I reach back and grab her legs and tighten the pressure on her head.

Her sister stands there and giggles, "Shame on you. You let that old, old, old man catch you like that. You're such a loser."

I tell the little ruffian, "Say, 'uncle.' Say 'uncle,' and I might let you go."

Jan glares at her sister as she makes one more desperate attempt to free herself. It fails. She whispers, "Uncle."

"Louder."

She gives me a squeaky little, "Uncle."

I tighten my headlock. "Louder."

Jan shouts out, "Uncle."

I free her. She jumps in front of me shaking her finger at me, "You, you're not a good grandpa. For Christmas, I'm requesting a replacement Grandpa. Got that, you mean ass OG." Jan glares at me as she speaks. She turns on her sister, "Grandpa got lucky. You're not going to be so lucky, June Josephine Stanton."

June Josephine Stanton puts up her fists and strikes a boxing pose. At the same time, she's plotting her escape route from her six minutes older and far more aggressive sister.

"Hey, like, he said it again. He said nigger again." June's attempt to divert her sister works.

"OG, is that like old-time hip-hop?"

"No, girl. That's the blues."

June pushes her luck. "Like, even I know that. Grandpa, that sounds older than you, older than dirt, is it?"

Jan gives her sister a quick evil look as I respond, "Yeah, you sure is right. I think Huddie Ledbetter recorded that in the late 30s, 1937 or 38, thereabouts. Do you like it?"

Jan takes a casual step toward her sister. June takes a gliding step backward. Jan asks me to play it from the beginning.

"I will if we can all have a truce until the song's over and we can talk about it, okay?"

June eagerly accepts the idea as her sister reluctantly agrees. I hand Jan my phone. "Look up the lyrics while it's playing."

June and Jan sing the lyrics along with Leadbelly. I help them out.

When the song ends, June looks thoughtful, purses her lips and asks, "Like, who's Leadbelly and why's he in Washington, D.C.?"

Jan adds, "Who's the bourgeois? Why were they turning Leadbelly and his wife down and calling them niggers? They just sound like mean ass white people to me."

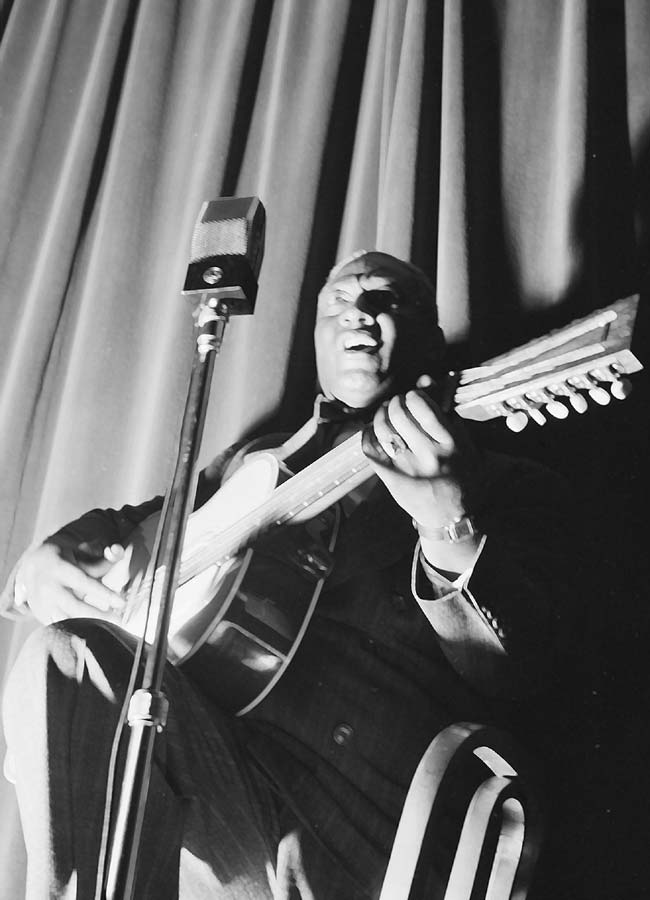

"June, Leadbelly's one of the great bluesmen. You need to learn about him. You can look him up on my phone. He was in the District to record his music for the Library of Congress."

I turn to Jan, "You're the bourgeois, the middle and upper-classes that believes that capitalism and the free market are God's greatest gift to humankind. The white bourgeois didn't rent rooms or homes to black people back then. Some are just mean white people, but most white and black bourgeois today claim to despise and abhor the word, "nigger." Still, most of the white bourgeois continue to profit from slavery, other forms of coerced labor, and racial discrimination."

"Okay, Pops what leftist line of propaganda are you feeding my daughters this time?" My son, Aaron, has crept up on us. He hands me a bottle of beer and drinks from his own bottle as he settles in next to me on the lounger.

"I'm just telling them the things they may not learn in school or from you."

Jan asks her father, "Do you know who Leadbelly is? Are we the bourgeois?"

June adds, "Leadbelly says, the bourgeois, like, called him and his wife niggers --"

"June, what have I told you about using that word? It's a disrespectful and hateful word. I don't want to ever hear you use it."

June pleads her case, "But Dad it's everywhere, like in all the hip-hop, and the other black kids at school--"

"June, you're not a hip-hop artist or the other black kids at school. People will not respect you if you don't respect yourself. Understand?"

Jan jumps in, "Dad, it's in Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn and movies and --"

Aaron turns to me, "Pops, you're still as subversive as ever." He turns back to Jan. "Why's your face so red?"

She shrugs. "Sunburn maybe ..."

Aaron turns to me, "Pops, don't be so rough on them. They aren't boys. They aren't Moses and me."

Jan's face gets darker, she clenches her fist, "No, we aren't boys! We're tougher than any boys."

June doesn't look so sure, but she backs up her sister, "We're not going to be pushed around by boys or any bourgeois." Her lower lip trembles as she stands shoulder to shoulder with her sister.

I turn to my son, "Man, what do you say to that."

"Yes, husband, what do you say to our daughters?" We all turn to see the tall, steely-eyed blonde bearing a tray of cold drinks and diced fruits that she places on the table next to the lounger. "This is a hard country, husband, especially for girls. Girls have to be tough and smart to survive, I think."

Gunda's my son's wife and the mother of the two tougher-than-boys hellions.

Aaron grimaces, "I didn't mean to say... I mean, I know..."

Jan adds, "Mom's mother was black and German. She had to be tough, right Mom?"

June addresses her dad, "Yeah, even in Copenhagen after World War II, Grandma had to deal with people calling her names and pushing up on her."

Gunda places a hand on each of the girl's shoulders and gives a bitter smile. "My mother married a white Dane, but they made sure all their children knew about their black grandfather and how to fight back and be smart about it."

The twins don't get much slack from their mother. My son understands who has the final word over the kids. I try not to smile as he again fumbles for a response.

"What I meant to say was that Pops used to play rough with my brother and me and ... ah ... well --"

I try to rescue him, "I understand, Aaron. I do, but your concern should be for me. I'm old, and a bit frail and these two rascals are way tougher than you guys were at that age. You should tell them to be careful to not hurt their old Grandpa."

Both girls explode in laughter.

Gunda smiles.

My son pats my knee in gratitude.

June grabs her Mother's hand, "Mom, do you know who Leadbelly is? Have you heard the Bourgeois Blues?"

Jan grabs her other hand, "He uses the "N" word -- twice -- in Bourgeois Blues."

Gunda sits on the lounge next to ours as she responds, "Huddie Ledbetter was from Louisiana, and his best-known song was, Goodnight Irene. I like Goodnight Irene very much. He was in prison more than once. He was a person that you would never want to pick on. I would like to hear Bourgeois Blues, please."

Aaron frowns as Jan plays the song again and she dares to sing along. June and I add our voices. Jan shows her mother the lyrics, and Gunda joins in. Aaron finally joins us but skips the "N" word.

As the song ends we're all laughing and talking at once, and Gunda asks us, "We just sang the word 'nigger.' Have we done something wrong here?"

I grab a cup of fruit off the table and try to answer, "Yes and no. Aaron thinks the word should be outlawed. I don't know how you would sing this song without saying, nigger. It would not be the Bourgeois Blues without the niggers."

The girls giggle.

Gunda smiles.

Aaron frowns.

Aaron addresses his daughters, "Listen, that word's so hateful I can't even fit it in my mouth. I was your age when a white girl at my school called me the "N" word because I accidentally bumped into her and spilled her lunch tray.

"'Watch out! you stupid nigger!'

"The whole cafeteria was looking at us -- at me. I just stood there. I didn't know what to do or say."

"Daddy, what happened?" June's reaching out to hold her father's hand.

Jan grits her teeth and frowns.

Gunda nods her head in sympathy.

I pat Aaron on his back. I can see the pain in his eyes and the slump of his shoulders, the trembling in his hands.

Aaron takes Jan's hand in his, "I was so angry and, and ashamed ... I don't know exactly why I was so ashamed. I still don't know why."

Both girls hug their father. He holds them tight.

I finish the story. "Moses poured his milk on the white girl's head. He beat the shit out of the two white boys that tried to help her." I have one-hundred percent of everyone's attention. "Both my sons were kicked out of school. The police were called. Our minister intervened with the mayor of our little town. We left Alabama two days later. The next time I saw Alabama was fifteen years later when I went back for my mother's funeral. But this could have happened in any school in the home of the brave and the land of the bourgeois."

There're tears in June's eyes.

There's absolute fury on Jan's face.

Gunda speaks softly, "Our country's far harsher on black people than Denmark was. There's so much hatred here."

I reach out and take my daughter-in-law's hand, "Look, to me, white, capitalist, Christian people invented the word, 'nigger,' and many of them don't want to be associated with their invention. But they are still practicing the same kind of Christianity and capitalism that was the foundation for the term nigger. Me, I think you take their invention and use it how you see fit. Use it against them. Use it to free yourself from the sting and stink of it. Use it to tell the true story of your country like Leadbelly does."

Jan stands stiff as a board, hands in fists, "Grandpa, did you punish Dad and Uncle Moses?"

I hold out my arms to Jan, "No. No, I didn't. I felt like I had failed them. I hadn't prepared them for what was coming -- what was inevitable. I want us to do a better job of preparing you two for the day you discover you are niggers in the USA."

Jan turns to her father, "Dad, I won't use the word around you, but I'm not afraid of the word or the people who use it. I'll use it when I need to."

June adds, "Like, we need to know the history of it, Dad. Maybe we can turn it against the bourgeois -- tie them up in their own history, okay?"

Gunda stands and takes Jan in her arms, "We'll learn together. We'll defend each other always."

Jan slowly relaxes and embraces her mother. But, I know my oldest granddaughter. She's more like her uncle, Moses. She's like Leadbelly. She's not the defensive kind at all.

Jan is war without quarter or regret. I hope June can be resolve and resolution. I want to be around a little longer to watch them in action.

I find the lyrics to Goodnight Irene. We sing it together.

Listen to Bourgeois Blues

And the lyrics

Listen to Goodnight Irene

And these lyrics

12/17/2018

08:03:13 PM