The irony that my recurrent childhood athletic failures produced happy times for my dad only occurs to me upon reflection from a perspective of the passing of half a century and more. That is not to say that he was happy with my failures; he supported my efforts and cheered me on, consoling me with the type of tenderness only a father can render to a son when I was unsuccessful. Rather it turned out that the result of failures provided opportunities that created joyful experiences for him -- and for me.

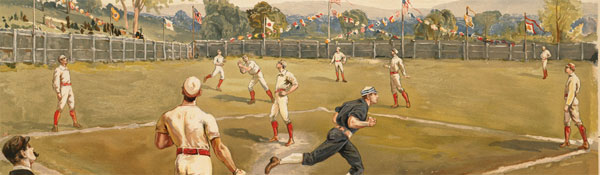

First, baseball. I received my baseball glove in May at my eighth birthday, interestingly enough given to me by my Uncle Jack. The source of my glove was unimportant; I practiced as faithfully as the average eight year old, first with a rubber ball but soon becoming confident enough to use a baseball. Games of catch with my friends, made up games with bat and ball, and similar activities caused me to imagine myself to be a skilled ballplayer and by spring of the following year, nearly nine years old, I went to my first tryout for our local Little League team.

There I was with my identifying number written on a piece of cardboard which had been salvaged from the packaging of my dad's shirts when returned from the cleaners, the cardboard attached to the back of my shirt with a safety pin. There were many boys at the tryout, most of whom I did not know, most older than me and, I realized as I watched, better at baseball.

I went to third base thinking that was the safest place for me. I missed most of the balls that the man who stood at home plate hit to me, ran them down as they went past, and found that throwing all the way to first base was beyond the range of my arm. At the conclusion of the tryout I suspected that I might not yet be skilled enough to make the team.

I was correct. I had failed, received the parental encouragement that, "It's okay. You'll do better next year," and was assigned to a "minor league" team composed of similar failed athletes. Except they were not similar. They were better than me. So my first year was spent mostly watching games, playing the minimum number of innings, and celebrating with my folks if I was able to hit a foul ball.

But, I told myself -- or perhaps my dad pointed out to me -- that I was, after all, among the youngest players. I just needed to practice more and get older. And I did, playing with friends or by myself, throwing the ball and catching it off the side of the house, swinging the bat, hour after hour.

The next year arrived, tryouts occurred; with my cardboard sign pinned to my back, I thought second base with its shorter throw would suit me better. I caught more balls than the year before and reached first with my throws more often. At bat against a fat boy who wanted to be a pitcher, I swung level and late and did not hit the ball a single time. It was back to the minor league for me, more time watching, a few more foul balls and even a walk or two.

Again, "It's okay. You'll do better next year."

I did get better. Practice produced results. I was able to catch and throw and hit better by the following year. But everybody else got better as well. And so I again spent my season in the minor league. A recurrent result every year. I never made it to the Little League team.

That final year, after the tryout and the by now anticipated failure, disappointment did not occur or, if it did, to no great extent. I realized that now I would be among the oldest and therefore likely one of the better players in the minor league. Finally, I thought, I would have a successful season.

I suggested to my dad that he should coach my minor league team. And why not? The coach of a Little League team had usually played competitive baseball at some level, the position carried a certain prestige, there was the enjoyment of working with talented players; the position of Little League coach was coveted and coaches often remained in place for many years.

A minor league coach usually coached for a single season, recruited from the pool of parents of minor league players. He would endure overseeing a group of failed baseball players which meant balls not caught, an apparently limitless parade of strikeouts and walks, short attention spans, and games that never seemed to end. My dad had grown up in New York City in the twenties and thirties, any baseball games he played took place on a blacktopped "field" lacking grass or dirt.

My dad took on the job. He clearly enjoyed himself, coaching with enthusiasm and patience. It was a happy time for the both of us. At home we talked about the games and the players, discussed strategies, and looked forward to each game. I played well that year, hitting over .300 and at shortstop cleanly fielding more balls than I bobbled. Rather than suffer through the torment of prior years of watching me fail he was able to cheer my successes and take whatever vicarious pleasure is there for a parent when the child does well.

He enjoyed more than just my play. He liked the kids who played and cheered them on and encouraged them, never angry, never disappointed, but always happy and with a smile. He was simply a joyful coach and genuinely celebrated with his players whenever something good happened.

The time after the final practice before our first game generated a story my dad enjoyed recounting for many years. He sat the team down on a bench and stood before us, telling the players to be certain to go to bed early the night before a game. Then, tongue in cheek, he offered admonitions that seem so quaint today but in the innocence of the fifties could be said with a straight face even as we all were in on the joke.

"No smoking, no drinking, no carrying on with women!"

* * *

After my baseball career ended, I was off to a boys' overnight summer camp, eight week sessions each, for the next three years. The camp had a "fleet" of perhaps half a dozen small sailboats. To be allowed to sail a boat a camper had to be considered a skipper, which required demonstrated competence in handling the boat. He was allowed to take along one or perhaps two campers who acted as crew. Campers who went out as crew really were just along for the ride though they might handle the jib sheet. Skippers were allowed to take a boat out alone so being friendly with a skipper was sometimes the best way to get to go out for a sail. If one were lucky, the skipper might allow a camper to sail the boat for a while, handling the main sheet and the tiller.

The requirements to become a skipper were clear. One had to be familiar with the boat, to identify and name the various parts; the main sheet, the shrouds, the tell tails, the reefs, the tiller and rudder and transom and centerboard. One had to be able to identify and name the various points of sailing; close hauled, broad reach, running free. There were the rules regarding right of way such as starboard over port, windward over leeward, overtaking boat keep clear, and there were the various maneuvers such as coming about and jibing. The requirements included being able to tie various nautical knots. Finally, there was a practical test, going out with the camp counselor in charge of sailing to demonstrate the actual ability to sail safely and competently.

I enjoyed sailing and aspired to become a skipper. But there were many other things at camp that I also enjoyed. There was baseball, swimming, card games and whatever else boys that age found interesting. Finally by my third year at camp I had sailed enough, had learned enough, had become skilled enough to take the test to become a skipper.

First was a written test which was administered to the prospective skippers as a group. I was excited that I passed this first hurdle and arranged to go out with the sailing counselor for the final step. He and I climbed into the dockside boat, I in the rear where I handled the tiller and the main sheet and off we sailed. I did all that he asked, sailing to various locations he pointed out, performing maneuvers such as coming about, and answering his questions easily and confidently.

"Good job. You passed. Take us back in."

I was silently joyous. I was a skipper! I could take the boat out alone. I could favor certain campers by taking them along. I had status.

For all the sailing I had done in the three summers at camp I had never brought a boat back to the dock. I came about and headed in with the wind nearly directly astern. The boat picked up speed and headed straight for the dock. I had no plan and no idea what to do next. We were going faster and faster as the dock got closer and closer. At the last minute the sailing counselor realized I did not know what I was doing and was sailing full speed for a head on collision with the dock. He leaped toward me, stretched his body out and reached over me for the tiller, at the same time that a panicked and primitive noise exited from deep in his throat.

"Noooooo!"

He threw the tiller all the way over; the boat turned sharply and missed the dock by inches. I remained silent.

I did not become a skipper.

That autumn after my last time at summer camp and my failed attempt to be allowed to sail a boat myself I found in a magazine a brief article about building a sailfish, which is a small sailing craft less than twelve feet long that one sat on, not in. A boat I could sail. I showed it to my dad and asked him if we might build one.

"Well, send away for the plans and we'll see then."

The plans arrived, we looked them over together, and my dad agreed to the project. We spent the entire winter building it in our basement. My dad had somewhere gained some modest skills in carpentry and would patiently show me how to do things or how to use tools that he bought. We laughed and joked while we worked. I could hardly wait until after dinner when the two of us would head for the basement to work on the boat. At an age when teenaged boys might rebel and become petulant or distant from parents, my dad and I buddied up building it. It was clearly a special time for him as well as for me.

Finally in early spring it was done, the final coat of paint applied, the sail ordered and received. It was only by a handful of inches that we were able to carry it out of the basement. We took our boat to a friend's summer cottage and launched. It floated and sailed! I spent much of that summer sailing on a local lake, often with friends but sometimes with my dad. I was a skipper at last, and my dad my crew. I wonder, still today, which of us enjoyed it more.

* * *

A few years later, the autumn of my senior year of high school, I was again at my familiar spot on the bench of the varsity football team. Unlike baseball or sailing I had not independently aspired to be a varsity football player; a number of my friends with whom I played pick-up games had encouraged me. Varsity football was a more serious activity and I had much to learn including things as basic as the proper way to put on the various pieces of equipment but as my senior season approached I had reason to be hopeful. I was even mentioned in a preseason article in the local newspaper as a player who might play a significant role. It had not happened; the combination of lack of size, speed, and any outstanding skill had put me on the bench once again.

My folks had never gone to any of the football games. I strongly discouraged them from attending because they were unlikely to see me play and I imagined their presence in that circumstance to be embarrassing to me. They had, but not happily, complied with that request.

My failure as a varsity football player notwithstanding I still greatly enjoyed football which meant I was glad whenever there was a junior varsity game; that meant I would get an opportunity to play in a football game. There was no glory or spectacle in those games. They were played on a practice field with no goalposts, no lines, no stands, and little grass. We played in our usual practice uniforms which were dirty, torn, without numbers. The games were coached by an incredibly ineffectual assistant who seemed to know little about football. There were only four JV games in a season. Nobody ever watched. But it was football and I played.

The final JV game had already begun when I looked across the field. There, standing alone along the sideline was my dad. How he had known there was a JV game that day I did not know; there was no published schedule. Perhaps I had mentioned it in passing at dinner the night before? And how did he get away from his drug store to be there? Had he called in a pharmacist to work that afternoon?

The game soon regained my attention and my dad's presence left my consciousness. It was a close game which like all the games seemed to hardly have begun before it was nearly over. I was playing defense in the interior line despite my small size. The situation at that point in the game, a moment which remains in memory, suggested that the opponent team would likely pass.

At the snap of the ball I outplayed, outmuscled, outquicked the man in front of me and was immediately in the backfield. As I expected the quarterback had dropped back to pass and I rushed at him. He was a quick-footed kid and stepped aside and began to run toward the end. I cut off the angle and took him down with a clean tackle. It was a nice play, a couple of teammates congratulated me, and then it was back to the next play. The game soon ended, I do not recall who won. I then noticed my dad was no longer there.

At dinner that evening I mentioned to my dad I had seen him at the game. Yes, he had enjoyed it and thought I played well and had seen me make some tackles. We spoke a bit more about the game and then off to other subjects. I was still a bit embarrassed he had been there, it was just an unimportant JV game.

The football season ended, our team won a league championship, I kept a program from one of the games that listed me with my number, size, and position as a memento. I had enjoyed my football career even if it had not been as successful as I had hoped.

Decades later, when my dad had begun his physical and intellectual decline, I was home for a visit. The innate joy with life that he had always carried was fading. As we chatted about this and that somehow the subject of my football days came up. My dad's eyes brightened, the expression on his face turned to a great smile, he became animated as he recalled watching me play football that day. He described in some detail that particular play and then spoke of "all your teammates ran over and were slapping you on your back."

All those many years before. I had no idea my dad had carried that particular happy memory with him, that he continued to experience such obvious happiness. His joy at that moment became mine.

That was the final chapter in the history of my successful sporting failures.

Originally appeared in Furtive Dalliance.

04/22/2019

08:14:16 PM