Her host family in England is just the same size as her own: two. The mother's name is Lindsay. She walks Sophia to the bus stop every morning and gives her her first English lesson of the day. Go to class. Stay in class. Go to training -- for once.

'Please, Sophia.'

Lindsay's a brave lady to house someone else's child as well as her own. Although, as Sophia likes to point out when Lindsay is mad at her, she does at least eat her vegetables.

'The school's going to call your father,' she says.

If this is a threat, it's not a very effective one. Sophia beams and slaps her bag of books like a merry mountaineer. Lindsay just sighs, and stares up at the clouds.

It's been a month since she first showed up at 14 Coldharbour Drive, two brand new Louis Vuitton bags clutched in her hands, her hair in a mess from the wind and rain. It had only been a short ride from the language school in Oxford city centre but tourist websites never mentioned the surrounding areas. The house seemed thin and dense and smelled of the wet clothes bunched up on the radiator in the hall.

All the English school had told the host families in advance was their students' names, origins and ages. Knowing that her student was fourteen and of European origin, Lindsay had bought a frozen pizza for dinner, a safe assumption made fatal by the instructions Sophia's ballet tutors had sent with her. They listed where she was booked for training after school, where she would need to taken to get replacement shoes and tights, her nightly exercise routine, and lastly her diet plan. Sophia took in the look of despair on Lindsay's face, and rifled through her English for the right words. She strode across the kitchen, took hold of the pizza box, and clutched it to her chest.

'I love pizza.'

That was where they began.

Sophia gets on the bus when it arrives and says hello to the other student passengers, who are walking up from their own homestays. One of the boys at the back calls 'Hi, Sophia!' in a tone that lets her know he's not really talking to her. There are a few small sniggers around the bus that disappear before she has time to look round to see where they came from.

There is another reason they do this, besides the fact that she's a girl and alone.

'Bye, Sophia!' another boy calls when the bus arrives at the High Street, because when they all get off to go to class, she doesn't even look up from her phone. She has something more important to do. As every day, she gets the 9.01 train to Didcot Parkway, and, as every day, when she gets there, she walks straight to the park south west of the station.

Mum went through here every day, she repeats to herself. Once, someone threw her shoes up into the trees.

She looks up into the tree, acknowledging every leaf, as if she could signal a stage-hand to pull them apart and find the shoes still there, hanging from a branch.

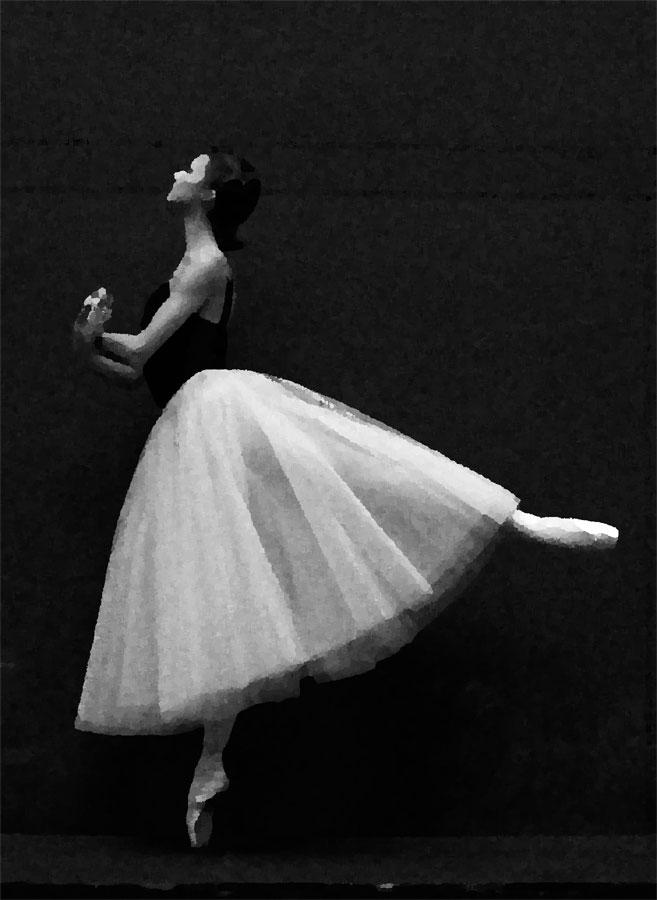

For years now, Sophia has had the feeling that something is out of order. She feels like a culvert leading off a river. It's not normal to develop into the exact build you need to have. It's not normal to get through an international ballet competition and not remember a moment of it because there were no words in your head, or for the first words that come to be 'That was alright' in your third language. It's not normal to win that competition.

Something was sacrificed for her to have these things. She thinks that the something must have been her mother. Sophia was four when she died, and she remembers her mother's face about as accurately as she might have painted it back then; dark hair, a red smile, and no more. But when she tells herself the stories, she remembers Mum's touch as light as a queen's, her voice which always sounded on the edge of laughter, her hands and arms which brought infinite comfort in only seconds. Sophia needs the stories to remind herself that she still has a soul.

After the competition, her tutors needed little persuasion to let her take English lessons over the summer, and even less to let her take them in Oxford. Only her father knows why she really wanted to come here, and he doesn't care, as long as she stays in training.

Oh, well.

She looks through the trees towards the edge of the park. Somewhere -- she hasn't found out where exactly and probably never will -- Mum used to pick blackberries with her own mum.. There were hundreds of them just lying around for the taking. She can't picture that story: where she lives there are no fruit bushes, but it's true. And there are more.

At the after-school club over there, they paint the walls with each new generation. Under three, maybe four layers, her hand-prints are there, in purple.

It's summer, but the air is grey and wet, she feels the weight of it against her. Her clothes cling to the small of her back and the insides of her elbows. She imagines her face from the outside; her make-up is probably rubbing off, and her forehead itches like it has some spots coming. The clothes and the make-up are all new, like her luggage, bought with money her father sent over after the competition. They're the first women's items she's ever owned and they felt like pictures in a magazine until she brought them here. These sensations were never part of her mother's stories but she narrates every one in her head just the same. Her head is a constant stream of words and her feet are heavy on the ground.

When it starts to rain, she walks down to the newsagent's and buys a paper and some chocolate. She holds them to her chest like a bouquet of flowers.

Saturdays smelled of newspapers and Dairy Milk. My grandfather always brought those back after he finished work in the afternoon. Sometimes he went to watch Didcot Town.

Until she was ten, she thought he was on the team.

'Hello again, Sophia,' the lady at the counter says kindly and Sophia fantasises that she's been recognised. Lighting low, music still, she bows her head, though the true grace of the gesture is expressed with the whole body. She can play the scene in her head. Yes, I am her daughter. Oh, she's very well, thank you. We live around the corner. Do you think Didcot Town will be promoted this season?

As she walks away, she tries not to listen to the muttered conversation between the lady and a customer she's been talking to.

'She's here every day. Think she must be here to learn English. Too young ... the parents ... it's cruel.'

She could wait here but she has an urge to hit the pavement. The shower passes and the sun is trying to break through. She keeps her eyes on the ground, watching her shadow with its bag swinging and the newspaper poking out from under its arm. Another of Mum's stories comes to her. She remembers the day she heard this one, remembers putting one foot carefully in front of the other along a run of bricks barely worthy of the word wall but which was scary to mount at the time.

All the people on the right side of the road have cats. All the people on the left have dogs. Do you think they've noticed? I guess that's a secret we know about them. Ready? And jump!

The story won't stay in her mind. She can't stop thinking of that word, cruel. Her father is not cruel. She remembers the day he picked her up from nursery. The day she met him. She'd never seen him before, Mum never told her anything, but she knew instantly who he was (it was our same eyes, she thinks now, they always look stricken -- she uses the effect constantly in her dance), and she ran into his arms screaming 'PAAAAPAAAA'. He gave her a chocolate chip brioche from his jacket pocket and said, 'Your teacher said you have been a brave girl. I can see that she is right.'

She told Lindsay about her father once, on a Saturday night over a Chinese takeaway. She didn't have the words for the story, just the facts -- her mother was from Didcot, she left to work in France after high school, she met her father but they broke up or something and she went back home to England to have Sophia. Then, when Sophia was four, her mother's accident happened.

'Can I ask what it was?' Lindsay said.

'She was stinged by a wasp. She was allergic. It was on the inside of her knee, I don't think she saw it.'

Someone tracked down her father, and he took her back to Lille with him. He gave her French and she grew into it, setting English aside. She told him she liked ballet and he arranged for her to train in St Petersburg: far from home, but it's all paying off now.

'And you've never come back here?' Lindsay said. 'To the UK?'

'He's usually busy, and it's so far to travel. It's better if I stay at school most of the time. I'm still studying now, aren't I?'

Lindsay didn't honour this witty reference to Sophia's truanting with a reaction. She had had a couple of half-litres of lager, and her face was tired.

'Alfie's dad left,' she said, 'but it sounds like your dad got you to leave.'

Sophia felt she was getting a glimpse into womanhood, like when she put on her new clothes, or when she got her period and Lindsay let her stay up late and watch Bridget Jones's Diary on ITV2. But she must have been too young for the conversation after all because Lindsay has not brought up the subject since.

Something sinks under Sophia's arm as she walks. The chocolate's melting. Oh no, she thinks. She stops at a park bench and eats it all on the spot, not pausing to break it up with her hands. She squeezes her cheeks together to absorb the sweet, homely taste and lets it melt over her teeth and tongue.

The angst isn't going to get to her, not today, because today is the day everything changes. She's meeting some people who knew her mother.

This visit is actually the last stage of her project; the first began almost a year ago. While searching her father's wardrobe for old clothes to give to Emmaüs, she found a black T-shirt, size XS. It was a cast T-shirt, but not one of hers. On the front was the logo for the musical 'Grease', and the name of a school. On the back was her mother's name, along with about forty others.

She took it to her father, wanting his reaction. He had always said that when he picked her up there had been no time to collect her mother's possessions, which could only mean the T-shirt had come from a time before.

He took it and held it out in his hands. She tried to see him as he must have looked to her mother; the gregarious junior accountant, concealing emotions as effortlessly as an ocean its trenches, except, of course, from her ...

'She left that behind one time when she visited me,' he said. 'I forgot to give it back. No more questions, OK?'

* * *

To love someone, Sophia thought, is to understand them. You can't love me any more, she told the T-shirt as she stuffed it in her suitcase for school, but I can love you, and that is enough.

The time she had between lessons, training and homework could often only be counted in minutes before she risked getting too tired, and she'd had the competition at her shoulder. She committed to no more than two weeks' worth of research on each name because every metaphor for finding something could be applied to the search. She had hundreds of leads and yet none led anywhere. So many Facebook profiles with faces disguised by sunglasses, so many LinkedIn profiles with nothing more personal than the writer's thoughts on SEO and emerging markets. Eventually she built up a collection of ten people who had definitely been at school with her mother, and contacted them through the various social media sites she'd found them on.

Dear ()

My name is Sophia Charbonnier. I am 14 years old. I am writing on the subject of my mother, Penny Carey, because after having done some research, I believe that you went to school with her. You may have heard that she died ten years ago. I were very young and I do not remember her well and so I am planning to come to Didcot in order to learn more about her. If you can tell me something, please share what you can via email, or if you would like to, we can meet up. Please tell me if this email is not appropriate for you.

She reads the replies she got every night and in almost every spare moment, either on her phone or from the copies she printed off at school, which are tearing from how many times they've been folded and unfolded.

Hi Sophia,

I don't think I've ever had such an important email! I remember your mother so vividly. She had such personality. I think I still tell people anecdotes about her to this day. You don't meet many people who make that kind of mark on you. I am reeling to hear that she is gone, I would have loved to see her again. I'd be delighted to meet you when you come to Didcot. Anything at all I can do to help you, let me know.

Zoe Langley

* * *

Greetings, young Sophia!

I hope you'll forgive me for looking up the domain of your email address. Ballet school, how very impressive. I have a daughter of my own who dreams of becoming a ballet dancer, but alas, she takes after me, two left feet. That's a British idiom, means you can't dance -- you may never need to use it. I was in a school play with your mother. I have a vivid memory of our PE teachers teaching us to hand-jive with very obvious reluctance. The girls got on better with it than we boys did, not surprisingly. There is a line in Graham Greene's 'The Power and the Glory', 'There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in' - I wonder if I witnessed such a moment for her. How humbling that is, knowing of her passing. I am truly sorry. I and all my family send our prayers and condolences to you and your father.

As you can see I have a tendency to witter on, and the older I get the less it is valued by anyone spending time with me. What I am trying to say is, you, young Sophia, have knocked at the right door. I will talk your ears off with anecdotes. Let me know the time and place, and I will be there.

Julian Cook

* * *

Hello Sophia,

First of all I will say I am very sorry to hear of your mother's death. I recognise it was a long time ago now, but I have lost my own mother and I know the pain never quite goes away. I hope you and your father are keeping well and life is good to you.

I'll be upfront with you -- the stories I have are not exciting. Neither my nor your mother's life was ever going to peak at secondary school, especially not in the statistically most normal town in England. But I remember she was a very creative person; always drawing or writing or telling stories. And she was a good person. I was not very close to her, but I still would have trusted her with anything.

I probably won't be the best help you can find. But if you still want to get in touch with me, please do. I'd be honoured to help you.

Matt Hilton

* * *

There was not much time and they were nervous to meet her alone, so she brought them all into one message, and they agreed to meet at a restaurant in town. When she approaches, they are already there at a table by the window with a space left for her. She swallows the last traces of chocolate remaining in her mouth and makes her entrance, head held high.

Julian Cook is the first to acknowledge her. Sophia found him through TripAdvisor reviews; he gives historical tours of Oxfordshire, so is probably accustomed to welcoming travellers. Although he must only be in his mid-thirties if he went to school with her mother, he has the genial self-assured air of the old senior managers at her father's firm.

'Here's the girl of the hour!' he says.

Zoe Langley is a slim, pale lady with a smile so large and bright it prints itself on Sophia's memory like a flash of light. Her Facebook profile revealed that she and her husband have a small but close-knit circle of friends who all walk their dogs together at weekends.

'Oh,' she says, her eyebrows coming upwards in sympathy. 'Sophia. It's amazing to meet you!'

Matt Hilton's LinkedIn profile had not been updated in three years, and described him as a 'business analyst'. His hair has thinned at the top since his profile picture was taken, but the grey round-neck jumper he wears makes him look like an illustration from an old-fashioned British school story. He gives Sophia a nervous smile and a little hum of cheerful greeting.

'Thank you,' Sophia says, forgetting her own hello.

The interior of the restaurant gleams in the midday sun, light-coloured floors and walls contrast with the clean black lines of the tables and chairs and the artfully overgrown plants. Nobody offers Sophia a children's menu or balloon, and she gets to keep the wine glass at her place even though she orders a Coke. The adults make conversation about the menu, the practicalities of parking and appointments later on in the day. She leans back in her chair and takes in her surroundings, restraining her desire to ask them questions. Everyone in the restaurant is happy. There are colleagues on lunch breaks, friends out shopping, parents with teenagers celebrating. A pizza with a layer of golden melted cheese browned like a dream catches her eye and she decides immediately she'll order one.

Maybe this will be the best day of my life, she thinks.

Zoe has also noticed the pizza. 'Do you guys remember,' she says to the two men, 'those slabs of pizza they used to give us in the canteen?'

Matt grins. 'Yeah. Dough like cardboard.'

'Yeah, and they were 50p.'

'That was a lot of money in those days,' Julian tells Sophia.

This is where they begin.

'The first night I ever spent away from home was at your mother's house,' Zoe says. 'It was her birthday, we went to Didcot Wave, the swimming pool. I was terrified of leaving my parents. Seems absurd now, I know, but I didn't want to miss Didcot Wave for anything. Her mum -- your grandma, I suppose -- was really chilled out. She let us stay up all night watching movies.'

'What about her dad? What was he like?' Sophia asks.

'I never saw him,' Zoe admits. 'I think they were divorced.'

They weren't, Sophia knows, but it must have seemed that way because of his odd hours. That must have been why he brought his daughter the chocolate on Saturdays. Connecting with her grandfather, even from this distance, she feels a flicker of safety, like someone placing a blanket on her shoulders.

'I could swear,' Julian argues, 'we did Romeo and Juliet for weeks on end in Year Seven. Some of the girls decided to put on their own version, though it was more like a pretend game than a play. They made Penny be Mercutio. They picked on her, since she was overweight.' He glances towards Sophia, who despite being the smallest at the table has finished not only her own pizza but also Matt's last two slices. 'And they thought it'd be funny for her to get killed off early.'

'Joke's on them,' Matt says. 'He's one of the best characters.'

Certainly he is in the ballet, Sophia thinks. His death scene is one of the longest in ballet history. It is unendurably tragic; it sets the stage for everything that follows.

'"A plague on both your houses!"' Julian exclaims, clutching his chest. 'What does dress size matter, if you can pull that off?'

'You were all in Grease with her. Who did she play?' Sophia asks. She had to look up the plot on Wikipedia; St Petersburg, characteristically, has yet to embrace it on any level.

'Chorus,' Zoe says. 'We all were. No talent among us. I suppose you're familiar with those sorts of roles?'

'Yes. I was in The Nutcracker last year,' she says. They make appreciative 'Oh' and 'Aw' noises. She ducks her head modestly and takes another sip of Coke, deciding not to mention she was Masha, and not just in the chorus.

They order ice cream and sorbet for dessert, and the atmosphere turns sleepy and peaceful. Zoe exchanges glances with Matt and Julian, then withdraws a small tablet from her bag and taps at the screen.

'We thought you'd like something more tangible. People didn't have cameras in their pockets in those days, so there isn't much, but with a bit of persistence we put together an album.'

Constrained as she is in her seat, Sophia can't think of anything to say or do that would be enough to express how this feels. 'Thank you very much.'

She scrolls through the photos, dragging her finger slowly, as if more abrupt movement might tear them. She braces herself for a face to reveal itself to her. Her friend Pasha from school has an anecdote about how his father didn't wear glasses until after Pasha was born and so he never recognises him in old photos. Sophia, of course, barely remembers what her mother looked after she was born. Did Mum have different coloured hair as a teenager? Is she in the background?

Convinced she is missing something, she tracks everyone who appears more than once and there is one girl who appears in all of them. Her hair is blonde but light brown on the underside. She has freckles from forehead to chin. She seems to favour a denim jacket featuring a purple flower on the right side. Her expression varies from an exaggerated moody pout in a shot crowded with other girls -- 'My thirteenth birthday,' says Zoe, 'we thought we were so cool' -- to a wide, innocent grin lit by centre-stage lights. In this one she's on a large box painted to look like concrete. Her legs kick out joyfully in a full skirt. She is alone on the stage.

'There she is,' Julian says with satisfaction. His finger lands next to the girl's face. 'That hairstyle she's wearing, Sophia, is called a beehive. She knew how to do them herself, she was tremendously popular ...'

The food in Sophia's stomach lurches heavily. Matt, in the corner, seems to have had the same realisation, as his eyes bulge behind his glasses and he mouths a single-syllable word.

'I've -- just remembered something,' he says slowly, as if every word is a physical strain. 'That girl -- her name was Rosie.'

Tension explodes like an airbag between them. Sophia feels her eyes, ears, entire body pinned down, smothered.

Julian blusters, forcing impatience. 'If she was Rosie, then who was Penny?'

'Oh -- ' Zoe begins, as if she's going to say something, but her pause is a second too long. 'Oh... Penny was that quiet girl.'

'The one who smoked leaves because someone convinced her they were weed?' Matt suggests.

'No ...'

'The one whose dad had an affair?' Julian says

'No, oh Jesus, oh God, bluh, I can't ...'

Zoe is collapsing into British gibberish. Matt stares down at his ice cream in horror; he seems to have disappeared into his own mind. Julian holds a fork in his hand like a gavel.

'Got it,' he says. 'Fringe. Thick jumpers. Madame Evans's favourite. Really good at French.'

'Thick jumpers,' Sophia repeats. Her tongue flubs the 'Th', so it sounds like 'tick jumpers'. Tick fringe. Tick jumpers. Tick French. All on the list, all part of the character sheet. Nothing of the dancer's role; nothing of the soul.

Another few seconds of suffocating silence go by.

'Sophia,' Matt says at last, 'I am so sorry. We've made a mistake.'

'If -- if you could just wait, we'll almost certainly remember something,' Zoe says. 'We've got time. We'll talk things out.'

'I have already waited,' Sophia says. The words feel like a script, a construct to tell them that something inside her is ripping apart. 'I have waited all my life.'

'We'll find someone else to contact,' Julian says. 'There's bound to be someone. Just a little detective work.' He seems to see something in Sophia's face, and falters. 'Please. Please don't panic, my dear.'

Words, images and sounds depart from her mind as the survival instinct suddenly takes over, lifting her up and rushing her towards the fresh air. The next sensations she becomes aware of are those of a rough wall against her cheek, and the burning taste of vomit in her mouth. A few people are approaching her.

'Are you alright, sweetheart?'

Gathering some self-possession, she bolts towards the shopping centre. This place wasn't around when she was little but she's glad it's here now, as it's got corners to dart behind and shadows to hide in. She settles behind a wall where no one is passing. She feels like an erupting volcano, rage and despair flowing and billowing out of her.

Why am I the only person in the world who remembers you? she asks her mother. What happens when I forget you?

This thought sends such a physical shock-wave through her that she fears she'll be sick again, and that would attract a lot of attention. Instead she bursts out in horrible sobs she can barely control.

She ought to have learned something from her father. She shouldn't have tried to find something that couldn't be bought with either money or work. She should have accepted what she had.

Once she can see more clearly she notices a clock in the shop she's facing. The ballet training she's signed up to in Oxford starts at four; she could make it easily, with time to sort her face out in the train station bathroom. For the first time since she arrived here, she actually wants to go to training; she could disappear into dance, as she's done so many times before.

But the number one thing they teach at ballet school is that practice can never, ever stop. Even with the utmost care her body could still betray her, and for four weeks she has been practically asking it to. Her arms and legs are aching now just from her emotions.The thought that she could lose ballet, just as she had lost so much else, does not, to her surprise, make her cry again; she just feels intensely, terribly tired.

The tears dry on her face and she straightens up to relieve her hamstrings. Her throat feels parched; her body wants her to take some care of herself even if she does not, so she makes her way to a café across the road. The colours are neutral yellows and greens, the seats neither soft nor hard, the prices typical. It smells of butter and coffee.

She orders a black tea. The routine of adding the sugar, stirring it and waiting for it to cool down is all she can manage right now. She thinks about kettles in England and samovars in Russia, and feels better.

Her phone vibrates in her bag. It's half past three, the time Lindsay is meant to pick her up from school and take her to training -- though they haven't actually accomplished this bit yet.

'Are you at class?' Lindsay asks. She sounds even more hassled than usual. Perhaps Alfie's had a bad day too.

'No.'

'Sophia.'

Sophia tries to tell her what happened, but she can't explain it in the right words; Russian verbs and French adjectives keep popping up.

'Why don't you come home?' Lindsay asks her.

'I don't have a home.'

'Will you come where your bed is, then?'

This very nearly makes her cry again. 'All right.'

She comes back to 14 Coldharbour Drive. Alfie is on his tummy in front of the TV.. On hearing her he rolls over and sits bolt upright.

'Hi, Sofa! Guess what?'

'Did you have a nice day at nursery, Alfie?' Sophia asks, sinking to her knees beside him. She has no idea what she wants even from the next hour of her life, but she wouldn't turn down a story about growing flowers or baking cakes.

'Your daddy's here, Sofa!'

'Khvatit,' she snaps. Alfie doesn't understand Russian, of course, but he gets the sense of 'that's enough', and turns petulantly back to the TV.

But there is a change in the scene. The light in the small living room brightens, the door creaks slightly. Socked feet shuffle onto the thick carpet. She turns around, and looks straight into a familiar pair of stricken eyes.

'Sophia,' her father says. 'Your teacher says you have been struggling.'

Previously published by Didcot Writers in their anthology 'The Most Normal Town in England'.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.