Star City Moscow felt a long way from Lagos, and the Baikonur Cosmodrome would be even further. Of course, from the Salyut space station, Abacha Tunde would be able to see all three; from 400 kilometers up, he'd have a sunrise every 92 minutes.

Abacha Tunde and Pavel Bucharev took their seats in the cockpit mockup.

Bucharev had been a hardened test pilot for the Red Army and flown on two previous Soyuz missions, T-2 and T-9. Bucharev had earned his seat. Abacha, on the other hand, had purchased his.

"And we're going to go five-sixty degrees, right?" Abacha asked the instructor.

"They noted that here," the instructor replied and tapped the clipboard in his hand.

"Okay, so when do we separate? Is that here?" Bucharev pointed to an open page in the thick manual. "Somewhere over -- "

"Right. That's it."

Abacha said, "It's negative yaw ... And we aren't going to do acquisition until after we've separated because we won't have anything to look at until six meters away, so ... "

"So does it matter which ... ?" said Bucharev.

"Here ... " Abacha slid over the keyboard and monitor -- a proxy for their flight controls -- to the veteran, Bucharev.

The instructor explained, "If you go ahead and hit enter, it'll start." Graphics of the simulated docking trajectory appeared on the monitor. "Then drag and drop here, and -- "

"So if I click this one up here, it'll get big?"

"No, not minus," Abacha cut in. "That's the one that diminishes it. But actually, go ahead and try it, just so you know."

The instructor nodded at Abacha's intuition.

Though the mission would not be made public, and the crew's spacecraft wouldn't actually be a Soyuz, all documents referred to the vehicle and mission architecture as Soyuz T-16Z. Officially, the T series was retired after the launch of Soyuz T-15, a flight Abacha had originally been scheduled to be on.

The simulator ran on next gen software and hardware, as did the vehicle Abacha was reassigned to. State-of-the-art 1986 technology would help automate the mission-critical docking procedures.

Cautiously, Bucharev aimed the cursor over the upper corner of the screen. "Right click?"

"Left."

Bucharev's eyes widened, then he nodded as if impressed and conceding defeat at the same time. "Hm."

"So now it's down there. You see it?" Abacha said. He knew his Russian sounded funny to the other cosmonauts. They often ignored him, so he couldn't help but feel a bit proud for getting the studious ear of a decorated cosmonaut.

"And it remembers where it stuck it? It's not totally gone?"

"Right," said Abacha. "Now let's take a look at the escape vectors."

"And what do all these F buttons up here do?"

"Yeah, don't touch those."

Abacha stretched his neck and got comfortable in his seat in the cockpit mockup.

"Okay," said Abacha, "I'm going to attempt to acquire. How long is our range here? Estimated range is less than that."

"Yeah."

"And azimuth?" Abacha answered his own question: "Should be about zero."

"Yep. Zero."

"And elevation should be about ... ninety?"

The mammoth structure of the Salyut space station rose above the cockpit mockup, up onto the planetarium-like screen in front and above them.

Bucharev checked the paper manual on his lap. "Let's see ... Hmm, that's not right."

With the choppy 1980s graphics and the solar arrays sticking out of the sides, the Salyut looked like a giant robotic dragonfly.

"We're looking at the view from the end of the arm," said Abacha. "That's exactly what we want to see."

Bucharev's role as mission specialist was to operate the robotic arm, a ten-meter, three-joint appendage that deployed from the payload bay. Again and again, Bucharev -- under Abacha and the instructor's guidance -- used the simulator to practice hoisting the docking assembly's mating adapter out of the bay, rotating the two-meter-wide ring to an upright position, and placing it within reach of a waiting cosmonaut -- a man who'd have his feet strapped to a platform on the outside of the station.

* * *

The Cold War Soviet military men who ran the operation had little room in their hearts for a Nigerian entrepreneur who'd sold his beach resort and life savings for a ride-along. Their animosity reminded Abacha how much he didn't belong; more specifically, of how strange it was that Russia would let an unqualified foreign national join the crew of a classified mission. At first, in the 60s, Russia had only invited Soviet European nations into its Interkosmos program, but later reached out to other allies -- Cuba, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Mongolia -- and recruited cosmonauts from India, Syria, France, Austria, the UK, Finland, and Japan, and was now in talks with the U.S. about joint on-orbit dockings. Russia had put the first black, Hispanic, and Asian in space.

When Abacha signed on with the program, he'd defended his actions, not to his fellow cosmonauts but to the Oba, the spiritual leader of Abacha's hometown near Lagos.

Abacha had insisted to the Oba that the dream would be shared. The Oba sat forward on his white sofa with leopard skin throws, listening with interest. White and gold adorned everything in the room.

"From up there, I will inspire the rest of us down here," Abacha said from his knees. "I want Nigerians to see a familiar face on their televisions. They will see one of their own working with people who are completely different than them, in an environment harsher than any place on Earth. And then they will recognize the power of cooperation, and all the factions will be united."

The Oba's white-robed, Kalashnikov-toting attendants warned Abacha with their eyes and posture to contain his hyperbole, but Abacha didn't need to say more.

The Oba understood. "Without peace, there can be no progress."

And yet, to most people in the community, Abacha had sold out his people for a frivolous, fleeting dream.

Payment secured a seat, but the specific mission and ship was for Russia to determine. Had Abacha known he'd be bumped from a science mission to a military expedition hidden from the public, he might not have given up his fortune for the ride, and he certainly wouldn't have gone around espousing the mission's virtues as a grand unifier of a nation in political upheaval. But when Soviet military officers show up to your hotel room, no matter how wealthy or important you might be back home, you do as they say.

"Don't be alarmed," one of the uniformed men at the door had added upon seeing Abacha's expression. "Space travel is a finicky lover. Last minute changes are normal. Your role on the mission will remain minimal."

That didn't mean as a space tourist Abacha would be free to do zero-g summersaults and gaze out the window the whole time. He'd already gone through eighteen grueling months of training to prepare for the five days on orbit. Though so-far vaguely defined, there'd be plenty of menial tasks to keep him busy in-flight.

Abacha's concerns did not center around boredom, or even safety. He only worried what would become of him upon returning to Earth. There'd be no telling anyone he'd been bumped from Soyuz T-15 to T-16Z or visited the Salyut 8T instead of the 7T. The T-16z and 8T did not officially exist. Every indication of the mission would be erased from history, as would Abacha, he feared, if he told anyone the truth.

"Next of kin?" the Soviet officer had asked in pre-screening.

"Only distant cousins."

That was probably one reason for diverting him, not someone else, to the T-16Z.

* * *

October 28th, 1986. Site 110/37. Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan: Abacha and Bucharev lay on their backs, facing skyward from the second row behind Commander Damir Snatkin and flight engineer Anton Globa. Abacha craned his neck to look out the side window. They were on the pad; the cryogenic LOX and kerosene tanks were ready to be lit.

Abacha eyed the adjacent Site N1, where four manned attempts to beat the Americans to the Moon had begun and ended. The second launch had come the closest; the rocket cleared the tower but crashed back down onto the pad twelve seconds later. The resulting explosion -- one of the largest non-nuclear blasts in human history -- had shattered every window within a six-kilometer radius. Residents 35 kilometers away had seen the fireball.

Abacha had to pee, and everything ached from hours of waiting on his back under his suit, parachute, harness, and sweat. He was ready to be weightless.

The sky over the steppe turned from an ominous crimson to deep blue. The planets emerged like the eyes of beasts from a cavernous slumber, and the stars appeared like shattered glass over asphalt.

The count began seven minutes before the closing of the launch window.

"Holding at T-minus five minutes," came the call through the headset from the flight director. "Waiting on ATL weather update." Both Abort-To-Landing sites had to be clear.

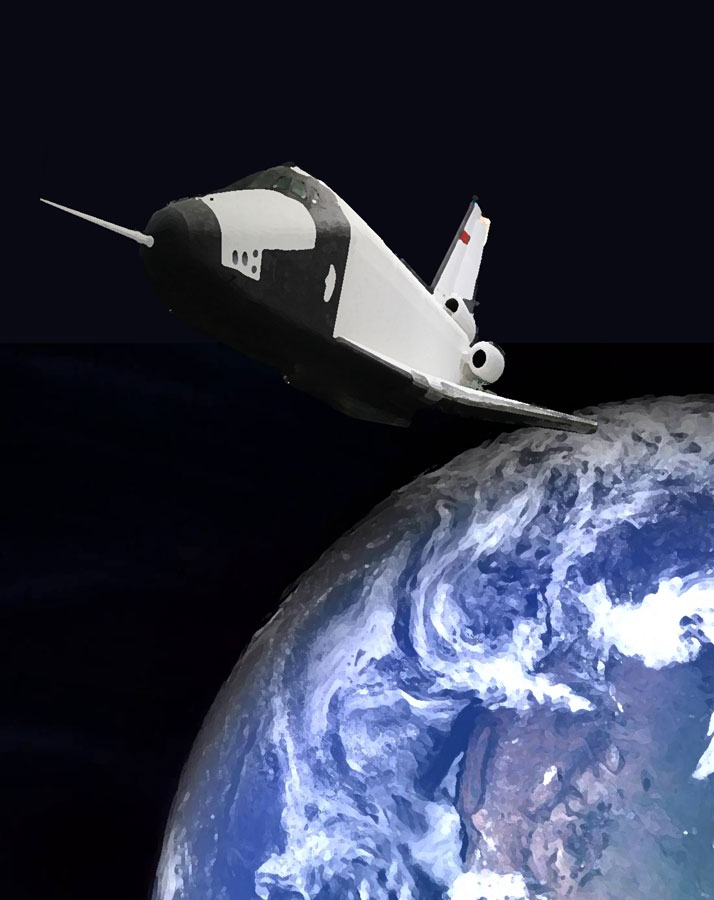

The pad filled with water and smoke. A plume engulfed the 3.5-million kilogram Energia rocket and Buran shuttle. The engines thundered down through the ground, out across the central Asian steppe, up the four side boosters and sixty-meter external tank, into the hull of the Buran upper stage, through Abacha's legs, up his spine and skull, and into his brain. And then the shaking turned violent.

At 07:48 UTC+6 the launch was scrubbed. "Pad abort," was the call, and the crew returned to quarantine at the Cosmonaut Hotel.

Unlike the NASA shuttle, Soviet hardware could boost the Buran into orbit in high winds, thick clouds, and in the Kazakhstan dessert's icy winters or blistering summers. The emergency crew escape system, however, could not. In one incident, the parachute had taken the capsule off-course and into the wilderness where the lone cosmonaut had had to fight off a grass fire, wolves, and ornery farmers. In other incidents, the cosmonauts had died, either on impact or from a slow asphyxiation because the hatch wouldn't open.

* * *

Some of the crew's pre-flight rituals would not be repeated for the do-over launch -- leaving red carnations at the Kremlin wall entombing Yuri Gagarin's remains, planting a tree along Cosmonaut Alley, getting haircuts, and signing the doors of their rooms. The rocket would not need to be rolled out and erected anew, since the launch was rescheduled for the next day. To this, Globa muttered, "Bad luck." They weren't supposed to see the rocket on the pad until launch day.

Again, the night before launch, the crew watched the 1969 Russian film, White Sun of the Desert and drank Champagne over breakfast. And again, Abacha felt a bit like the Oba, surrounded by an entourage of officials as he and the crew marched toward the base of the rocket, which would have dwarfed most buildings in Lagos.

The day after the cancelled launch, the families -- and no one else, due to the secrecy of the mission -- again gathered in the Cosmodrome viewing gallery. The sun had just come up, and Abacha had no one to see him off.

He repeated the long climb up the metal staircase to the hatch atop the rocket; the strapping-in and checklists, the backache and full bladder, and the waiting. For the Russians there with him, Abacha knew the worst part was the guilt of what they were putting their families through. Each wife had been assigned a surrogate -- someone to talk them through things, drop the kids off at school, pick up groceries, or comfort the grieving spouse and children in the event of tragedy.

The booster caps lifted off with a jolt.

The voice of the flight director rattled in Abacha's ears. He could almost hear the ground crew gnawing their nails while he listened to the chatter between the various teams, pilot Globa, and Commander Snatkin.

"Close and lock your visors. Engage oxygen flow."

Abacha obeyed. An image of the Apollo 1 tragedy flashed in his mind: three astronauts trapped and screaming into their headsets as the pure-oxygen environment of their capsule ignited on the pad and burned them alive.

The sound of Abacha's own breathing filled his helmet.

"We have a go for main engine start."

"Go for launch."

... seven ... six ... five ...

The vibrations turned to rumbles, and the seat began to shake. Abacha tensed. A burst of light blinded the view on the monitor. A plume of black smoke emerged, then the sky vanished behind a bigger cloud of white for the split second before the Buran erupted skyward atop a blaze of fire.

"Liftoff."

Burning ten tonnes of fuel a second and accelerating past the speed of sound in under a minute, the rocket stack tore into the Grand Beyond, thrusting the first ever crew of the Buran boldly into the darkest night.

His second spaceflight, Anton Globa must've known what rookie Abacha Tunde was thinking. It'd been less than nine months since the vehicle most similar to theirs, NASA's Space Shuttle Challenger, broke up shortly after liftoff, killing all seven on board. Globa raised an arm against the crushing g-force and gave Abacha a thumbs up. Impossible as it may have seemed under such intense shaking, all systems were nominal.

Abacha kept calm, confident in his training and crewmates.

47 minutes after the Buran orbiter moved into its 391/396 circular orbit, Globa fired the reaction control thrusters, and the Buran began its drift toward the Salyut 8T, the station that didn't exist. Compared to the U.S. Shuttle Orbiter, the Buran had poor maneuverability in space. In both cases, every drop of fuel had to be budgeted carefully.

Two hours into the flight, the crew opened the payload bay doors.

"Go for on-orbit operations."

Still en route to the station, Bucharev practiced maneuvering the robot arm in and out of the payload bay with a double-joystick console. Abacha watched the veteran stealing peeks out the window but refrained from reminding Bucharev to trust the monitor.

The next day, Snatkin checked over the EVA suits, and Globa got acquainted with the on-screen guidance for precision docking.

Abacha tried to stay out of the way in the cramped confines of the orbiter. When not engaged in a task (he found great joy in flying back and forth between decks of the vehicle to fetch tools and equipment), it was hard to be alert to the calls for tools or an extra hand when such a dreamy view of the turning Earth loomed just out the window. What struck him most was the distribution of lights. Europe flared in the brief night while Africa stayed true to its Dark Continent moniker.

The Salyut 8T space station orbited 6,500 kilometers ahead, and 612 kilometers closer each orbit.

"Comrade Tunde," Globa called across the cabin. Of the three Soviet military men on board, only Globa appeared to have any sense of humor. Unlike the others, Globa did not speak to Abacha with derision. On this occasion, Globa even smiled. "There is a bottle in my duffle bag."

Bucharev handed out slices of pickled cucumber, and Commander Snatkin shook out a blob of vodka in front of each cosmonaut. Mesmerized by the oscillating sphere of liquid floating before him, Abacha nearly missed the cue:

"Davayte vyp'yem za uspekh nashego dela!" the commander toasted, and the rest of the crew repeated the phrase in unison before gobbling their bubbles.

Abacha's apprehension about drinking on the job disappeared when Globa handed the bottle back. "That's enough," he said, and gestured for Abacha to return it to the duffle bag. As Abacha understood it, leaving a bottle unfinished was poor etiquette in Russia. Maybe Globa read his mind, because he explained, "Space travel is not a party."

The Russians bobbed up and down, giving each other looks. The commander gave Globa a nod, and the red-faced cosmonaut at last let Abacha in on the nature of their mission. "A salvage mission," he said. "Salyut 8T is a dormant military station. Unmanned. We will install the docking mechanism, perform the docking, bring the station back online, and return home. That's all." He slapped Abacha on the arm, and the momentum made them tumble apart.

Later, Abacha asked Globa, "What happens if we can't get the station back online?"

The Salyut T8 had lost contact with the ground in February of '85 when telemetry reported an electrical surge. A second surge killed further attempts to reestablish contact, leaving ground crews with no means to diagnose the orbiting station. Drifting uncrewed and in silence, the twenty-meter station would eventually deorbit on its own and burn up or crash back to Earth.

"We must not let that happen," replied Globa without elaborating.

Three days after launch, the crew of Soyuz T-16Z caught up to the Salyut.

Everyone was up early preparing for the docking, and by 06:00 they could see the first of sixteen daily sunrises sparkling off the white wing tips and open payload bay doors of their own spaceship.

Globa fired the thrusters to bring the Buran closer to the Salyut.

Abacha floated over to the airlock window, which led out into the open payload forward section of the bay. He saw the robot arm, docking adapter ring in its claw, protruding from its cradle. Installing the adapter was an essential workaround of the station's lifeless automated docking system.

To Abacha, Globa said of the job, "Sixty or seventy percent chance of success." Commander Snatkin gave Globa a side-eye scowl, though he didn't argue with the assessment.

The operation would be like performing a heart transplant, but with bulky gloves, fluctuating light and temperature, and while flying weightless 500 kilometers above the Earth at 28,000 kilometers an hour.

"And if the adapter doesn't work?" Abacha dared to ask Globa. Snatkin popped his head through the opening to the second deck and narrowed his eyebrows at Abacha as if offended. He gave a snort of a laugh, and said, "Then we figure out another way in." Snatkin would be the one going outside to install the adapter.

The crew had spent thousands of hours training for the mission, on the simulator and in the pool. They'd suit up and go under water, where the buoyancy mimicked that of space, and rehearse on full-sized mockups of the Salyut and the docking adapter. Bucharev would practice swinging the arm with the adapter pinched in the claw, over time gaining millimeter precision. Weightlessness affected everything, and the viscosity of water had been known to trick spacewalkers. The pool added drag that space didn't, which taught the cosmonauts to put more force into their actions than was necessary.

Snatkin had over five hundred hours in the pool, working with the arm and feeling what it would be like to slide a 180-kilogram doughnut out of the Buran's body. Sure it weighed nothing in space, but he couldn't see around the instrument's bulk, and any force he applied had momentum. Once the thing got going, it kept going. And the slightest bump could mean disaster.

"Stay back," Snatkin barked at Abacha, who'd gotten too close in his hovering over the shoulder of the commander.

Abacha laced his fingers through the cargo mesh in the ceiling to keep from floating where he shouldn't. He watched the aft end of the station sweep past the monitor and across the cockpit window.

The Salyut was tumbling. Somehow, with their limited fuel and weak reaction thrusters, Globa had to maneuver the Buran to line up the open payload bay with the tip of the station and bring the two vessels to within six meters of each other but without letting them make hard contact.

A hand jerked Abacha by the shoulder. "Hold this," Snatkin ordered, giving him the left glove of the EVA suit. Abacha stared at the glove like it contained a hand. Unlike the American version, the semi-rigid, one-piece Orlan-DM spacesuit had flexible arms and a hatch through the backpack. Snatkin had donned all but the gloves and helmet by himself, and in under five minutes.

Abacha and Bucharev helped the commander with the helmet.

Globa dropped the perigee to make the Buran skim beneath the Salyut, giving the crew a better look. Abacha, stoic by nature, had to remind himself to breathe.

The Buran maneuvered with subtle thrusts. A fly-around confirmed the station remained in one piece, though the thermal lining around the airlock had lost its sheen, likely from solar radiation.

"Aligning for intercept of the forward port," Globa announced to Mission Control.

Every few seconds, Abacha felt a small torque and saw out the front windows the Buran rotate and pitch to match the motion of the station. As the vessels became better aligned, it was the Sun that appeared to tumble, swirling in the sky as if the solar system were coming to a dizzying end. The station flickered in the incoming sweeps of light as it slowly turned along its long axis like a spit roast. Then, abruptly, Abacha's perception flipped. He again viewed the Sun as a stable point of reference and felt nauseated by the Buran's oscillations. He fixed his gaze out the window at the station's solar panels. They looked crooked.

The Buran was coming in fast. Abacha clenched the laminated contingency checklist. His heart jolted as the station filled the view out the cockpit and then disappeared. They weren't docking nose to port, and Globa had initiated another series of short thrusts to orient the Buran's open payload bay to cup the Salyut's port end. The stunt felt like a zero-g version of a delivery van, side door flung open, skidding into a parallel parking spot.

Crosshairs appeared on an otherwise black screen. The Buran pitched, yawed, and rolled in tiny increments as Globa fine-tuned the approach. Panel lights flashed. The station filled the view. No one spoke until ...

"Soft contact. Target acquired." If he'd felt either stress or relief, Globa's voice did not betray it.

* * *

Abacha helped Commander Snatkin into the airlock, which served as passage to outside via the payload bay. Abacha ran through the checklist three times.

"Go for airlock depress."

Snatkin gave a thumbs up from the midsection of the airlock window then opened the last hatch. Without hesitation or so much as a glance at the Earth to his left, he disappeared out of sight. There'd be no tethers for this spacewalk. The slow dueling rotations of the vessels made the risk of entanglement too high.

Commander Snatkin appeared on the monitor. Somehow, he'd already found his way to the Salyut and had his feet on the lip of the station's docking port, and a hand on a small section of railing by his head. The grainy video and rapid shifts in sunlight made him hard to make out.

"Sunset in two minutes," Abacha said into his headset mic. Whether or not it had been his place to chime in, nobody rebuked him.

Snatkin would hold on through the 92-minute night; he must've been freezing. Abacha wondered if Snatkin had finally stolen a peek at the Earth. It made Abacha uncomfortable to watch the commander just bobbing around in the void doing nothing. What a waste of time. Although, with six hours of life support in the Orlan-DM spacesuit, nobody appeared to share Abacha's trepidation. And, being honest with himself, Abacha knew his unease didn't really arise from a concern for time management.

Whatever thoughts might bubble up in Snatkin's mind, he'd be forced to swallow. A person out there, all alone in the cold shadows of the unearthly night ... Any number of disquieting thoughts could creep forth from the basements of Snatkin's mind. Try as he may to hide them in the shadows and crannies of the station, any demons a space traveller had buried down on Earth would surely part the soil to follow their owner into space.

Globa let out a little thrust to orient the Buran. For a second, Abacha thought the protruding male port of the Buran was going to crush Snatkin against the female port of the Salyut, but the Buran stopped short, hovering in place just a few meters away.

Bucharev worked the joysticks, positioning the adapter with the arm.

"Sunset in eight seconds," said Abacha. Unable to hide his tension, his voice came out high pitched.

Bucharev brought the arm in for the grapple.

"Four seconds."

The claw released.

"Acquired," said Snatkin.

"By what means?" said Mission Control.

"Got it right here in my hands."

"Just a reminder, Commander, that you're not tethered."

"Correct," Snatkin replied to the flight director. "Free floating with the ring now."

It took Mission Control ten minutes to agree to Snatkin's request to stay outside during the docking. Snatkin argued he could inspect the seals and connections better than the cameras -- not even the one mounted on the claw end of the arm could cover every angle. It made no sense to go back inside for the docking only to come right back out to perform the checks.

Snatkin waited away from the port, along the side of the station where he locked his feet into a railing.

Globa fired the jets to coax the spacecraft to port, and a satisfying clunk and dull thud reverberated through the Buran as the docking ring retracted. Hooks and latches activated. The station and spaceship became one.

Another day dissolved into darkness, and another night dragged the wake of another sunrise. Looking both heavy and weightless, Snatkin crawled the circumference of the newly formed bridge to confirm the seal. Had he looked, he'd have seen the eastern-European Soviet Block pass by below.

* * *

From inside the Buran, Snatkin began the process of opening the three hatches that separated the crew from the Salyut. Before and after each hatch, he took careful samplings of the air with a handheld device.

"Adequate," was Snatkin's verdict each time.

Guided by the lamp on the top of his helmet, the commander disappeared into the manhole-cover-sized opening, emerging twenty minutes later to give the OK to open the airlock.

A rush of icy, metallic-tasting air flooded the Buran as the two cabin pressures equalized.

The Salyut hadn't seen a watt of power in months, maybe years, Abacha guessed. The life support and electrical systems were never meant to endure the temperatures of raw space. Hotwiring the station could spread whatever plagued it to the Buran, stranding the crew without vital systems like the air recycler, suffocating them within hours. Better to work the problem systematically.

Until the recycler got online, the Salyut could only support the carbon dioxide exhalations of one person at a time. Snatkin, Globa, and Bucharev took turns going into the crypt of the Salyut to diagnose and repair. They wore wool sweaters and winter caps and returned after each shift shivering and sullen. Whatever lay inside the Salyut remained obscure to Abacha.

"Classified," said Globa of Abacha's exclusion.

It took the better part of the day to work out the Salyut's electrical problems. A sensor made to keep the batteries in the solar panels from overcharging had failed. Six batteries were flat; the other two, fried. A telemetry issue had kept Mission Control from picking up on the problem.

From inside the Salyut, the Russians fixed the sensor and rewired the batteries, bypassing the dead ones and lopsided solar arrays. Then Globa fired the thrusters, using the Buran to tilt the attached station so the surviving panels faced the sun.

The station once again ran on its own power, albeit at a fraction of its former strength.

With the main objectives of the mission appearing to be accomplished, Mission Control expelled their tension with subdued congratulations. The crew might have expressed jubilation, but the faces around Abacha were more grim and stoic than ever.

* * *

"Re-attempting to undock from Salyut," Globa reported.

Nothing happened.

"Third attempt."

Nothing but a dull grinding sound. The docking mechanism would not release the Buran.

Abacha thought it probably related to thermal stressing caused by the rapid day-night cycles, or maybe the port had gotten too much of the Sun's radiation. He refrained from sharing his assessment; surely his crewmates were having the same thoughts.

"You and me," Snatkin told Abacha and gestured out the window. "Now's your chance to be a real spaceman."

Abacha stole gazes at Bucharev and Globa. Each nodded. Abacha had done far less time in the pool than his crewmates. Not enough to achieve mastery.

"Don't worry," Globa reassured him. "None of us has experienced this scenario."

That wasn't reassuring.

Snatkin helped Abacha prep his helmet and heart monitor while the others gave the plan a final check. While Snatkin thrived on pressure -- he'd been doing this for twenty-five years -- Abacha had never in his life been tested so fatefully.

He hovered at the airlock. A moment of contemplation while Mission Control confirmed everything. For better or worse, success depended not just on his performance or his crew's, but upon the manic dedication to detail of thousands of scientists and engineers. People's entire jobs centered on making contingencies and thinking up problems to throw at the cosmonauts during the sims. But had they thought of everything? Were the mockups right?

An Atlantic hurricane swirled past the nose of the Buran. Cape Canaveral and the Gulf of Mexico were in for a walloping.

Abacha mentioned tethers, since they didn't have the competing rotations to contend with anymore.

Snatkin replied, "We don't have tethers because we don't need tethers."

"We brought vodka but not tethers?" Abacha said under his breath.

"Just don't let go. You'll be fine," Globa told him.

Abacha got outside first. He held the handrail beside the door, which led out into the payload bay, while Snatkin floated out behind him.

Abacha's suit had a leak.

"Try moving your arms around a bit."

Abacha rotated his shoulders, and then checked again. "Seems fine now."

"EVA proceeding."

They climbed along the railing that lined the inner wall of the bay and used the cylinder formed by the linked ports of the two vessels as a bridge to crawl over to the Salyut.

Bucharev used the arm to take a small platform out of the payload bay. He passed it over to Snatkin, who attached to the side of the station, just beside the stuck docking adapter.

Snatkin strapped in his feet and got to work testing for an electric current.

"It's quite a sight," Abacha said, unable to keep from looking over the wing tip of the Buran at the Sahara and Mediterranean. Nigeria was just out of view beneath the wing. Then the vertigo kicked in. Just as he'd been warned, his head really did feel like it was spinning.

Don't look down, Abacha thought. He closed his eyes for a moment and tried again to watch, this time with better results. He'd presumed Snatkin's aversion to watching the Earth came from his staunch professionalism -- the beauty of the living blue Earth on the dead backdrop of space could steal anyone's focus; or maybe Snatkin had simply been hardened into apathy by decades of Soviet military service. But now Abacha wondered if the reason was fear.

Abacha checked his vitals. "I'm reading two-sixty hPa." The pressure in the suit should have been around four hundred hectopascals. "Topping off." He adjusted the pressure nozzles, guessing the pumps had ice blockage. Not a problem if it melted, which it did. Then his headset malfunctioned. He could talk, but incoming speech kept cutting out.

The EVA went on.

The Earth moved out of view. The Salyut space station in front of him proved no less mesmerizing. Abacha waited to be needed and watched the sunlight scour one half of the station's tin-can shell, its solar arrays like industrial wings.

Mission Control watched every move through the helmet cams and cameras in the Buran and on its robot arm. The basic plan was to shove something inside the adapter ring to manually disengage the latches, though Abacha hadn't recalled Snatkin bringing out any tools.

"Okay, now over there." Snatkin pointed to the other side of the port but offered no direction as to how to get there. "It's fine. I'll be here," he added when Abacha hesitated.

Abacha navigated hand over hand, down to eye level with Snatkin's platform.

"Sorry, I've got hold of your feet," Abacha said. "Okay, okay. Just get on with it."

Abacha let his legs float up and like a gymnast on the rings pulled himself beneath the bridge and up the other side, careful not to release one hand until the other had purchase on a railing.

"Go. Night is coming," Snatkin urged. And then to Mission Control: "If I push the hitch I get no resistance."

"Proceed as planned," came the cryptic reply.

"Okay, I'll tell you what we do now," Snatkin told Abacha. "You're going to stick your hand in right here to hold this latch open on this end while I go back into the Buran's payload bay and hold open the other end."

"The other end?"

"Are you paying attention, cosmonaut?"

"Yes, sir."

"Now stick your left hand in here and hold on tight to the railing with your right."

"Okay."

"Excuse me, what?"

"Yes, sir."

Abacha did as he was told, and Bucharev worked the arm to come pluck Snatkin off the Salyut and drop him back in the payload bay. But if Abacha pushed against the latch, the counterforce lifted his feet. "Sir, my legs keep floating up."

"And I'm off structure," Snatkin barked back from the Buran's payload bay. "If you don't like it, hold on tighter."

Globa's voice crackled in Abacha's ear, "It'll be over in a minute. Just hold on until then." The problem seemed even more obvious up close. One half of the adapter ring was in the shade, the other in the sun. Since the temperature difference had made the aluminum expand, they probably just had to wait it out. In less than ten minutes it would be night again. Nobody cared. Abacha kept his mouth shut.

"Both latches open," Snatkin declared.

Abacha's heart rate rose. He let his feet drift and focused on keeping his hands in the right places. Mission Control had rarely, if ever, addressed Abacha directly, but now they told him to turn his head away from the Buran so they could watch for the coming sunrise through his helmet cam.

Minutes later, Abacha reported, "I think I see light, Commander." A thin crescent had begun to glow against the silhouette of cloud cover.

"Okay, that's good," said Globa. "I'm just going to apply a little thrust to try and wiggle the adapter loose."

"You are?"

"Just a wiggle, but hold on and keep watching that sunrise, okay?"

"Okay ... Sir."

Mission Control said, "And when you're ready, Globa, we concur you've got a go for separation,"

"Pardon?" Abacha said. "Mission Control, can you clarify 'separation'?"

"Thrust," said Snatkin. "Yes, Mission Control, we understand we have a go for thrust."

"Copy."

"Okay, Abacha, you ready?"

"Yeah, I'm holding on tight but -- " Abacha's mic cut out.

"Go for separation."

Without a bump or nudge, the Buran eased out of the station's port. A hand-width gap appeared between the two vessels.

"Guys?" said Abacha, but nobody could hear him.

The distance kept growing. A meter now. Then two.

No thoughts preceded Abacha's next move. Only reflex. He bent his knees ... and pushed off.

Head first. A torpedo across the void. Reaching, stretching, tearing his lungs with the shriek of a madman and warrior, straining every vein, leaving his perch behind. He sailed on an instinct to bridge vengeance and self-preservation, giving up control to gain liberty in the timeslip between vessels. Abandoned, he'd put faith in physics and taken the leap from the crumbling edifice at the edge of the growing chasm. Momentum. Inertia. Three seconds till impact.

Two.

One.

He snagged the orbiter by the tailfin, barely hooking his fingers around its edge. As if riding a shark, he hung on with all fours while the continents flew past on his left.

Hyperventilation barely contained, he slinked down the tail and onto the open door of the payload bay.

He spotted Snatkin working the latch on the primary airlock behind the base of the arm. Fury boiled up from Abacha's gut, and he launched. Missing the target, he struck the robot arm, hung on, and kicked wildly at Snatkin, knocking him against the hatch. They wrestled against the wall of the bay. Snatkin cocked a fist. Abacha knocked it aside and countered with a swing of his own. He landed a blow square in the commander's facemask. Snatkin doubled over backward -- his feet just nicking Abacha's chest -- and tumbled along the girding of the bay floor and into the airlock at the far wall.

"Close the payload bay doors," Abacha yelled into the headset to Bucharev and Globa. Still no response.

Snatkin skittered crablike across the floor of the bay and pounced. Abacha dodged, but Snatkin caught his shoulder. They each kept a hand on the airlock handle while scrambling to hit, push, and grapple the other man. The thick fingers of Abacha's glove dredged Snatkin's suit, desperate to tear it or grab on, for something to leverage so he could toss the slimy bastard off into space.

Abacha let go of the latch and threw his arms around Snatkin. He smashed the top of his helmet into Snatkin's mask. Snatkin head-butted back, etching a spider web of cracks across Abacha's field of view. Again and again, they tried to drive their foreheads through the glass and into each other's faces while reaching around for a hose to yank out.

Suddenly, like whiplash, Abacha's whole body jerked away from Snatkin. The trailing appendage that was the robot arm had plucked Abacha by the backpack and was taking him from the payload bay.

In a grand humanoid gesture, the arm flung him from the Buran. Tumbling, Abacha caught a glimpse of the spaceship every half second as he spun. Each time it shrunk more distant.

"Sorry," said Globa's voice through the headset. It'd be the last word Abacha would hear from any of his crewmates.

He flailed for the body of the Salyut. The hull slipped past beneath his fingertips, out of reach. A boot dinged an antenna and barely slowed his inertia. Cast adrift, he screamed to mask the silence. He lost sight of the station. The globe and its continents of diseases and human indignity, its clouds of lightning and clammy air, and its oceans of trash and despair all roared back from the other side of his cracked facemask. Earth as one entity: unified in that not one bit of it gave a fuck about a spoiled little African left alone to rot in space.

The top of his head smashed through a solar array. His feet snagged in the busted panels and loose wires. The metal burned his hands even through his gloves, but he had no choice but to hang on. He no longer feared falling, only flying off into the void. He watched the night approach, and he watched, dazed and transfixed at the same time, as the Buran faded to a slowly gyrating dot against the cloud-covered planet.

In the last moments before darkness swallowed the ship and its crew, Abacha saw something flutter out of the payload bay. Then a another piece, and another. The Buran was breaking up. The thrusters fired, but the spacecraft only tumbled faster. To a backdrop of East Asia's coastal lights, the distant remnants of the Buran coughed a flash of fire. Orange and blue streaked the atmosphere as the ship burned up and disintegrated.

And now ... Night. 92 minutes of silent darkness. 92 minutes of contemplation. 92 minutes alone. The only human alive not currently on his or her home planet.

Abacha's heart thumped in his ears. His lungs pulsed over the whir of the suit's life support. He could hear his blood and taste bile. His jaw trembled, needing to shout, but what was there to say? No one was left to shout at.

A hot wave of nausea followed by icy calm rustled up his legs, through his chest, and lodged in his throat. His fate was sealed. Here he was, above the crowd. Above the Earth. Above all the world's conflicts and religions. Here he was, about to die above it all. ... They'd left him to die. Left him. Abandoned him.

He tamed his anger before it could corrupt him. Breathe. ... Not much breath left. Save it. Don't waste it on cursing. Deal the next blow. Save your breath to take control of your survival ... however short-lived. Or save your breath to wish the planet goodbye.

* * *

The hot glare of day ignited off the far end of the station, raced up the hull and blasted him in the face.

He moved hand over hand along the thin edge of the solar wing, back to the body of the Salyut where he crawled on his belly, wallowing in a psychotic haze; numb, sweating in the sun. But he continued toward the entrance.

He hammered hard on the hatch. Each blow resisted. Worse: it pushed back. He almost lost his grip. The only thing more terrifying than clinging to the outside of a deserted space station was the thought of letting go. But when he paused from working the hatch to rest, the thought resurfaced. He could, if he wanted to. His head shook side to side in his helmet against his will. First, try harder to get inside. They'd said it could be done. Those bastards. Those dead, stupid, fucking bastards ...

Focus! Open the goddamn hatch already.

Through the storm of the mind, through the walls of disbelief, fear, rage, and unretractable tears, he clenched the wheel lock with his left hand and hammered the railing with the side of his right fist. He kicked and yanked the railing back and forth and screamed at it until a bolt popped free, then another. He paused to watch them twirl through their plumes of dust then moved aside to let them pass across his visor on their way out into nothingness.

Just open the fucking hatch.

He didn't want to have to wait through another 92 minutes of darkness. He held the hatch with both hands and turned himself into a jackhammer, thrusting feet-first until one end of the railing broke off. It spun round and round on a single bolt. Abacha let go of everything. Just for moment before quickly grabbing back onto the wheel lock. But it had felt empowering.

That option, at least, remained in his control. Little else.

Once more, he took his left hand off the wheel lock of the hatch. He stared at his right gloved hand and relaxed his grip. A gap of space appeared between his palm and the handle. One centimeter became five. Then ten. All he'd have to do is close his eyes and wait.

But he realized that, in fact, he couldn't just cast himself out into the void. Not willfully. His muscles would not obey the brain's command. Such was the instinct for self-preservation.

He snatched the segment of railing from its last mooring and pushed off of the hull, catching himself with one hand on the wheel handle of the hatch. With the piece of rail wedged in the wheel, he heaved. The force torqued him off the hull. The backpack smacked the upper lip of the port. He rolled off. Tumbling the length of the station, rolling, scraping, dragging, he flailed for something, anything, to grasp. His knee banged a solar panel. He grabbed the neck of an antenna. It bent and twisted but held.

After translating back to the port, he continued to pry with the railing segment. In a bout of fury, he hammered and stabbed while anchored with his free hand, until at last the wheel turned, and the latch unlocked.

"Bastards," he muttered through gnashing teeth, though the anger was beaten out of him. Weakly, he chucked the length of railing end over end at the Earth.

Indifferent, Nigeria slipped by below.

* * *

Dim lighting and frosted surfaces greeted Abacha in the narrow confines of the abandoned station. They'd left the power on, diminished as it was. No heaters as far as he could tell, though. He didn't dare take off his suit. Not yet.

The lights were too bleak to see all the way to the end of the long tubular station. Along the surface he arbitrarily labeled as the ceiling were nets holding randomly-shaped bags, packets, and boxes into bins. Along the sides and floor, ice covered and endless array of stowage compartments closed with sliding doors and drawers rather than netting. Farther inside, past a dead computer terminal, Abacha found the air cycler unit. It hitched and gurgled, but appeared to be humming along.

"Adequate," was the word Snatkin had used to describe the conditions inside the Salyut.

Abacha took off his helmet. The air stunk. Acrid. Metallic. Frigid and damp, like old wet laundry and a leaky refrigerator.

He left the suit on to stave off the cold. It helped, but he still trembled.

Without his helmet, the noises of the station were haunting. Distant clicks and a near-subsonic thrumming -- the sounds of the gossamer thread keeping Abacha alive. It confused him that they'd left the life support on at all. Had they been expecting someone to come get him? Then why the trickery and deceit? He had the shivering thought that maybe they didn't leave the power on for him. He quickly ordered his mind to rein in its psychosis before it overwhelmed his judgment. At this point, a clear head was as important as air.

* * *

He needed water. Later, food.

Moving along the wall, he paused to glance out a tiny window. No Earth. No Moon. Not even a star. He couldn't have left orbit though. Not without a large boost. If anything, the station was drifting lower, destined for the same fate as the Buran.

One thing at a time. First: water.

He wished he'd brought the length of railing with him inside for something to bang off the ice with. All he had were his padded fists and feet. They worked, but he worried the exertion would overwhelm the CO2 scrubbers, so he tried to stay calm and regulate his breathing, pausing after opening each stowage compartment to slow his respiration and heart rate before battering open the next one.

He found blankets. He pulled one out, shook off the must, and cast it adrift to use later. Later ... The thought seized him. The word put a time variable on the ordeal. He had no idea how long he'd have to be there, or where the experience was headed. Best to think moment to moment, he decided.

Before finding water, Abacha got curious about a plastic shoebox-size container he found among some chemistry equipment. Floating in a cloud of sample bottles and microscope slides, he unlatched the box. He didn't jolt back, or toss the container aside. His heart rate didn't spike -- not right away, anyway. It took a moment to register what he was looking at. Spiders. Big, hairy, frozen, dead spiders. Four of them. He brought his face close and squinted at them in the dim light. Something brushed the back of his neck. He whipped around, flinging the box of spiders and bringing his hands up to defend himself.

The blanket. Just the goddamn blanket. And now there were frozen tarantulas floating around the cabin.

Abacha closed his eyes and took a breath. Just find some water, he thought. Before you start to hallucinate from dehydration.

He kept checking compartments until finally he came across a large cache of two-liter water jugs. They, too, were frozen. He hadn't thought about that.

Gloves off, he lifted the panel cover off the compartment with the air cycler and wedged a water jug in behind the radiator pump. It would take time, but the residual heat would thaw the water.

"Now what?" he said out loud.

He felt like a fly in a puddle. When most people saw a dead fly in water, they assumed it had drowned. That wasn't usually the case, though. Unable to get out no matter how hard it struggles but unable to stop trying, it inevitably dies of exhaustion. Unless something comes along and eats it first. Abacha floated aimlessly, exhausted, unable to relax. Every time he began to doze, he jerked awake, re-horrified by the situation. He couldn't help ruminating on the betrayal his former crew had inflicted upon him. He took no consolation in their deaths.

Over the course of an Earth-length day, the station began to warm. The heat coming off any individual light or electrical component was barely noticeable to the touch, but each combined with the waste heat of the imbedded life support system -- plus Abacha's body heat -- to bring the interior air temperature up to a little above freezing.

He translated along the corridor over to one of the spiders, which had stuck to the wall. He could probably eat it if he had to. He wondered if it'd be better to do it before or after it finished thawing. More at a loss for what else to do, Abacha peeled the creature free and brought a leg up to his mouth and pinched it between his teeth, hesitated, then snapped it off. He crunched it up and swallowed quickly, tasting the ice more than the leg.

Abacha sighed. A single spider leg offered almost no nourishment, and even less in the way of progress toward getting home.

Home. The concept felt foreign. Hopeless.

The seven-legged spider twirled slowly, legs splayed. Arachnids were hardly what Abacha pictured when he thought of military endeavors in space. Russia must have been doing some kind of biology experiments in the Salyut. Any signs that the station had been used for spying or weaponry had either been purged beforehand or Abacha just hadn't found the it yet.

He kept looking. The cabinets near the middle of the station housed equipment related to the electrical or dead radio and telemetry systems; compartments his former comrades had already dissected. Over the coming days, he ventured farther down the corridor, terrified at what he might find, yet compelled to keep exploring.

Days passed. Abacha ate the spiders, but they were no longer frozen and crispy, and they hardly satisfied his growling stomach. The springy-then-bursting texture of the abdomens made him gag, but less each time.

The balmy five or six Celsius had been welcome reprieve for the better part of a week. Unfortunately, not every compartment and container had been sealed off from the warming cabin air. The station began to stink.

One odor, though not the strongest, came from a duffle bag on the ceiling by were he'd come in. He should have noticed it right away but had floated right past. He unhooked the duffle from the netting, held his breath, and unzipped it. Dog food. Two ten-kilo bags of what should've been dried kibble but had been soaked through by a nearby leaky pipe and turned into sacks of soggy mold.

* * *

It was darker farther forward. The overhead storage nets bulged with cargo, and the cabinets in the walls had been left open and ravaged. Drawn to the narrowing depths of the station, Abacha walked the wall with the tips of his fingers, advancing even as the knot in his belly told him to stay back.

Then he found the rats. Three frozen little bodies packed neatly into a plastic box.

He resealed them and pushed the container to the back of the drawer and closed it. So what? The Soviets were probably thinking ahead to a crewed Mars or Moon mission. It made perfect sense to study the physiological limits of animals in space before subjecting humans to new extremes.

* * *

The stench of the rats slow-roasting against the radiator grille at the back of the air cycler made Abacha retch. He'd be cleaning up bits of vomit for days. In the hours it took for the rats to cook, he distanced himself and rummaged through more compartments.

Behind the bundles of trash bags, past the floor-to-ceiling sacks of laundry, he uncovered a hatch.

After dining reluctantly, then ravenously, on his rats, Abacha moved from window to window to inspect what lay on the other side of that mysterious hatch. It did not lead out into empty space. Hidden in the shadow of the solar array, a small module protruded from the side of the station. Waste storage, he supposed.

He'd gone outside through the airlock twice in the week since being abandoned on the Salyut T8, both times to jettison his accumulated bags of urine and feces and the spoiled dog food. He had no means to refill the life support gasses in the spacesuit once they ran out, though, so each time he'd waited until the smell became unbearable.

With hopes high that this newly found module was a place to store his refuse, Abacha donned his suit just in case the room was not sealed, then turned the wheel lock and opened the hatch.

So stuffed full was the module with white cloth bags of varying sizes that Abacha could not even tell the size of the confines. He took off his helmet and immediately threw up. Despite the subzero temperature of the module, a chemical-like stench overwhelmed him before he could identify it. But once he backed away and recovered, it became obvious that the smell was of death.

He stuffed handful of coffee filters into the folds of an old undershirt, which he then tied around his mouth and nose, preferring the body odor of some unknown cosmonaut to the rot emanating from the module. He returned to close the hatch, and in his haste caught an edge of a bag in the doorframe. The thick round door rebounded off whatever thawing object had been stuffed and tied inside the sack.

While Abacha tried to coax the sack back into the module, a part of the object slid out into view. Matted fur. The pads and claws of a paw. He peeled back the cloth to reveal another leg. Four in all. And a leather muzzle strapped over the head of a dog.

Abacha carefully replaced the animal where he'd found it and sealed up the hatch, encouraged by the frosted surfaces that the dog, and whatever else lay stored in the auxiliary module, would remain frozen and preserved.

A week later, Abacha returned to the module. He'd ignored his growling stomach as long as he could. Two more weeks, perhaps a month, passed, and all three dogs had been consumed.

* * *

Abacha watched the crux of night creep over a swath of land he couldn't be bothered to identify. With each sunset, the planet seemed to shrink. He'd been staring out the window for more loops around the planet than he could count and wondered how long until the Salyut's orbital decay began to break his flying dungeon apart. Live or die, he'd grown indifferent. Neither prospect inspired him to pull away from the window. Only his growling stomach could do that.

He dug deeper into the auxiliary module. This time he found the remains of a chimpanzee. Unable to bear the sight of its face, Abacha kept the little humanoid figure in the cloth bag while it thawed, and while he reached in with the glass from a broken light bulb and began the long, horrific process of slicing and sawing through a joint.

In removing the light bulb from its socket in the ceiling, something weird had caught Abacha's attention. A little black dome protruding from a panel beside the socket. It must have been a sensor of some sort, but he couldn't discern the purpose. At any rate, he ignored it. Until he found another. Five in all, he spotted, spread along the length of the hull. The sheen of the black plastic domes made them look newer than the rest of the station.

After slow-cooking the hand and forelimb of the chimpanzee and eating it, Abacha used the largest bone to hammer off one of the dome caps. He must've floated there a good ten minutes, trying to piece together the implications of what he'd discovered.

A camera.

That little psychopathic eye just kept peering right back at him, unblinking, and unperturbed that its debauchery had been exposed. If there'd been any doubt the camera was working, a tiny red light pulsed from behind the circuitry like the stoic heartbeat of a stalker.

Abacha smashed the camera with the bone. Rage burned in his veins. Again and again he stabbed, hammered, and clawed at the shattered mount in the ceiling. Plastic shards exploded in his face, and each blow propelled him back. Still, he returned to lay siege to the icon of betrayal.

The tantrum plunged the front half of the station into darkness.

His breaths shallow and rapid, Abacha drifted. ... Alone in the dark. Wilted. Defeated.

Why? Why was it there? What did they want from him? Then he tried to deny it and blame his ego for the misunderstanding. Why would he even think the cameras related to him? Was it so strange that ground control had wanted to monitor the station? He hypothesized that at one time, living animals might have been the only residents. No need for a cosmonaut to keep an eye on them in person. Especially if the experiment was to see how they fared in a long-duration, microgravity environment, it only made sense to record them and study the tapes later.

He popped the covers off the other four cameras but refrained from violence for fear of knocking the whole station offline. Blinding the cameras by stuffing shreds of laundry in the insets worked just as well. Abacha set out to find the tapes.

Over the course of several months, he searched every compartment along the main corridor of the station without uncovering any further clues to the nature of his internment. What he had found, however, was another chimpanzee corpse in the auxiliary module. It had become routine: chipping off an icy chunk, thawing it enough to peel back the fur, and slow cooking it. He tried to deny that the smell of roasting primate flesh enticed him. And he hated that it sometimes tasted good. He preferred to suffer the ritual as a necessity. He didn't eat every day. Only when his stomach growled. But even with rationing, he eventually consumed both chimpanzees.

He ventured deeper into the storage module, past the skeletal remains he'd desecrated. All the way to the back. That's where he uncovered the station's darkest secret.

Four of them, this time. One by one, Abacha pulled the corpses from their cloth coffins, out of the module and into the main corridor. After setting them in a hovering formation, he floated and stared into the dead eyes of his new frozen companions. Though their eyes were the most evocative, that wasn't what he noticed first. Their flesh was naked. No fur. No clothes. All were male; early 20s.

The first one he examined had an abnormally small head compared to the rest of its body. Perhaps it was an alien. That's what Abacha wished for, but the delusion dissolved upon inspecting the other three. Each had his own deformities. A misshapen leg with a clubbed foot. Withered hips. A hunchback.

Abacha tried not to think about why they'd been brought to the station and instead worked to make each his companion. He gave them names. From time to time, he'd notice the smell but for the most part accepted the burning in his nose and lungs as a feature of the ambient air.

He gave them turns at the window and taught them geography. "Those are the Great Lakes coming up now. Count them. You can see all five."

But no matter how much he spoke to the men, and no matter how much he imagined they spoke back, he could not completely delude himself out of reality. He was floating helplessly and hopelessly with four dead and decaying human beings. Ultimately, Abacha's own degrading mind was still his best, worst, and only comrade. And he wasn't yet insane enough to suppress the truth. He felt his instinct for self-preservation collapse. He knew now why the cosmonauts and the still-living people on the ground -- his kidnappers, his deceivers -- had trusted him, an African, to go along on a secret military mission. And he knew that his role in the mission had not ended with the departure of his crewmates. Abacha Tunde, the closest proximity to a "real" space traveller, was the subject of the final phase of the Salyut 8T experiment.

An almost-welcomed distraction from the swirling thoughts pressing out against the walls of Abacha's head: his stomach began to growl.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.