Chapter 5: Kevin's Story

For a while Robin and I kept our relationship a secret. It wasn't exactly forbidden, but it was frowned upon to shack up with a colleague. Understandable. I remember the morning after our first night together. She studied my bookshelves as I was cooking pancakes and eggs for us in some complicated and time-consuming manner. I'm a good cook. I like to play with spices and other details. She wasn't exactly bad, but food preparation wasn't her thing. She liked to "keep it simple."

"You have a copy of Lolita on your bookshelf," she mentioned.

"Occupational hazard," I replied, nearly losing a pancake I was about to flip. Fortuitous choice of words, because that could be taken any number of ways. The book was practically dangling its adolescent legs from the shelf. I knew exactly where it was. Place of honor. Quite prominent. Originally I'd been a member of the academic choir, adding my tenor to the general worship. Exquisite language, titillating subject matter so respectably presented. The titillation, though ever present, didn't officially count. What counted was the portrayal of love, of yearning, and the extraordinary wry, ironic, deluded, and yet so heartfelt and emotional language. This was not pornography. this was not misogyny. This was literature at its best. I was in love with Lolita, the girl. I was in love with Lolita, the book. It seemed so right. A masterpiece. As an English professor, I was a custodian of works of language, and this particular gem was worth keeping on display.

Or so I thought until Robin challenged my unexamined world.

As Robin's view on the issue became more evident, I felt lucky that I hadn't written my doctoral dissertation on Lolita, as I had at some point seriously considered doing. I never told Robin -- it conveniently never came up -- and, getting to know her sentiments on the subject, I was determined that she need never find out. There was no point. The omission allowed me to pretend that I wasn't quite as enamored of Lolita as I originally was. Before Robin ground sand into the lens through which I had previously looked at Lolita.

Robin's test for everything was gender reversal. Example: What if women started stoning men to death for being unfaithful, as men across the globe and across vast stretches of time did to women, with legal and religious sanction? The likely end result: pitifully few men left on earth.

On the subject of Lolita: Imagine a book of a compulsively effusive and sentimental woman lovingly and obsessively abusing a young boy, screwing him up, as the saying goes, for life -- and this book then becomes the most touted love story of the century.

Story of everybody's life, I nearly quipped, thinking of women and Freud and all sorts of faults we generally put at the doorstep of women, especially mothers, for lack of anywhere else to put the blame. Luckily I said nothing.

"What then?" She pressed. "Would it still be one of the best novels of the twentieth century? Would it still be called the most beautiful love story of all times? By anybody? Would it?"

I thought of a movie scene of a young boy having a sexual encounter with his mother; it had been dreamy and had felt a bit far-fetched and discomforting. It didn't make it to movie of the year or love story of the century status. I can't remember the title, or the director. One of those French film makers. Anyway, the best I could do was answer her by avoiding a direct reply. "You can't expect me to be an English professor and not have read Lolita. And since I happen to own many of the books I read . . ."

"You don't seem to own a copy of Margaret Atwood's Handmaid's Tale."

Touché. I didn't even know what the book was about, though I had of course heard of Margaret Atwood. And so it went. In the background my nagging guilt at once upon a time having been enamored of Lolita always nipped at my nerves.

By the time we had covered the issue of Lolita several times over the years, I have to admit, I had lost most of my enchantment. Looking back, I see how Lolita was, and probably still is, a sort of eloquent handshake among intellectual men. At first I resented having to pretend that I didn't like the book. I wasn't sure anymore that I did like it all that much. But I really didn't want to give up that handshake among peers in a club where membership was more or less obligatory if one wanted to be accepted in polite academic society. An intelligent woman's inner male was, incidentally, entirely welcome to join the handshake and the club. Robin, who was highly intelligent, was the first woman I heard taking a stand against everybody's infatuation with Lolita. And, as far as I know, she only did so privately. I know she had written some notes about it, but nothing was published. It could have been academic suicide. Not that her academic life was all that blessed with vitality anyway. I even warned her: "Better not air your opinions about Lolita too much in public -- it could be considered heresy, a special subsection of sexism, to deny men their harmless literary thrills."

"I know," she said. "And that's what bothers me the most, because this definition of harmlessness makes men immune to any type of censure. As women we will get insulted, but we must not say so, if, as you say, we wish to abstain from intellectual suicide. And let me get this straight: Freedom of speech demands that misogyny and pornography be allowed, but their critique must be censured?"

Intellectually suicidal or not, Robin was on the mark about this brilliant verbal celebration of a middle-aged guy dominating a young girl. I am ashamed to recall that at least one published critique I read even did the typical rape defense on Humbert Humbert. Lolita had it coming. She was the one who did all the seducing. Yup, she certainly had it coming. At her twelve years to his forty-some, she clearly had the upper hand with her wiles and her beguiling ways. He clearly was the powerless quarry caught in her snares.

And so it goes. Male found innocent. Female to blame. But what Robin also got around to showing me in the end was that, if a forty-something man is in the power of a twelve-year-old girl, or, for that manner, of any woman swaggering down the sidewalk in miniskirt with a cigarette dangling from her lips, then the relative power of the adult male is decidedly overrated. And the censure of women being child-like, naïve, and incompetent is sadly misplaced when all we ever do in society is encourage them and prefer them and reward them for being small, weak, docile, and so on.

"The difference between men and women is this," Robin once said. "When women get sentimental, no one gets hurt."

Lolita isn't dangling from my bookshelf anymore. I didn't toss it. I gave my copy to the public library which, as Robin didn't fail to point out to me one time, still had a waiting list for its four copies decades after publication. Yes, she made a point of putting things like that to the test. This was in comparison to Nora Roberts books, for example, where after the first year or so, there's no longer a waiting list. In fact, they sell off the extra copies they originally acquire for the early demand. Certainly there was a longer waiting list for Lolita when Robin checked this out than there was for any of the other ninety-nine of the top ranked one hundred novels of the twentieth century, none of which had a waiting list at all, or so Robin informed me. I didn't check.

Sometimes it scared me to be a man with Robin as witness.

I remember so much. Sweetness and magic. But also exasperation and bitterness. One day I came home late and found her crying on the balcony. She wasn't looking at the trees swaying in the dusk. She was just crying quietly, blindly. What have I done this time? I thought. Turned out I hadn't done a thing. She had read in an email signature from a writer (male, what else?) the following riddle:

"What do you do with a naked woman on a boat? Answer: First, you read her poetry."

I smirked. Fortunately Robin still had her back to me and didn't see my face. I speedily removed the smirk, knowing with one of my rare intuitive insights that it was not a wise facial expression just then. What made me smirk was the "naked woman." A smirk of self-protection. Robin had pointed out to me often enough when men thought of sex, they frequently got embarrassed, and to get over their embarrassment, they then had to make light of it with endless off-color wit.

She told me she felt physically ill with this quote. "It's like being slapped, in public, with the truth. And that's the last straw. Men use truth as a cudgel, as a weapon, to beat us down just a little more in each encounter."

"Explain," I said, feeling dense.

"We want to be admired. We want to be seen. We want to be heard. We want to be loved. We want our poetry read. We all do. You guys do, too. Only, when we do it for you, we do it respectfully and unobtrusively and without fuss. You, on the other hand, design T-shirts that announce how women and girls wish to be admired and worshipped like goddesses. And then you proceed to taunt us with this truth endlessly and without mercy. You taunt us with our vanity. You taunt us with our desire for love. It's not funny. It hurts. You tease us for being alive, for being human, for being real. In my sad soul I revisit all the instances where I have quietly supported a man's fragile ego, including yours, without making fun of it. Women have quietly put crowns on your heads when you wanted them most, put scepters in your hands when it made you feel better. How often in the last five thousand years have we read your poems without somehow twisting the truth like a knife of contempt and belittlement into your gut? There, there, little boy. I've read your words. Now can we please just do what I want? Yes? And now one guy realizes the truth: That women, also, wish to be seen, heard, taken seriously, given their own crown and scepter of the moment. Hallelujah, I suppose. But then he goes and makes the truth into a cudgel. There, there, little girl. I understand that I must read your precious words. Then can we please just get on with what I want, which is, you guessed it, have sex."

No, I can't say I remember her speech word for word. She was in the habit of making elaborate speeches, and I do remember how she didn't take a noticeable breath for at least two or three minutes while delivering them. I was stunned, not only at how eloquent she still was even in the middle of shedding tears, but also at how defensive I felt about the whole thing. We don't mean it that way, I wanted to say. It's just funny.

I have to admit, there were days when things were so bad between us, I thought she would leave me. She didn't. I'm not particularly proud of my less than illustrious role in all of this. I don't know what I would have done had she left me, perhaps for one of her dancing partners. Presumably I would have pretended not to care. I would have pretended that if you love someone, you set her free. But it would have been a pretense. Then again, maybe my whole life has been a huge pretense of one sort or another.

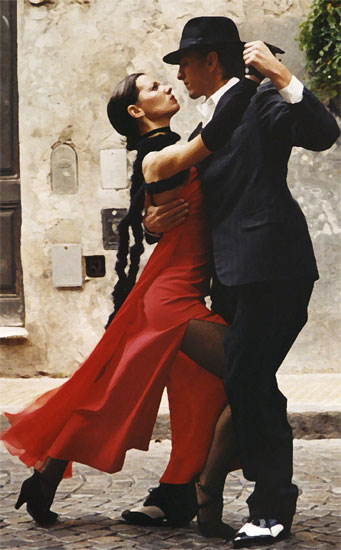

For most of our life together, I honestly had no idea how vulnerable she was and how much the desire to dance was part of her essence. After I started going out dancing myself, I wondered if I would ever meet anyone who had known her. I never did. I did not look very hard of course, because I kept telling myself it was none of my business to spy into Robin's life, even in retrospect. She, of course, would have simply called me a coward, exhibiting my usual inclination of not wanting to know, not wanting to see.

She never hesitated to call me a coward to my face. Particularly with respect to my deplorable (to her) and chronic lack of passion. For most of my life I was convinced that being dispassionate was the preferred way to be. There are world religions based on being dispassionate, for crying out loud. For me it had started with the early cliché indoctrination that boys don't cry. Since I was a boy and liked being one, I had better conform to the rule. The only emotion acceptable in a boy, presumably because it was not entirely avoidable, was anger. Other than that, everything had better be mild and bland. Robin taught me how for women it tends to be just the opposite. Anger is strictly forbidden, but the other emotions are more or less encouraged. Particularly love, of course.

So we have men who are not allowed to love matched with women who are not allowed to be angry. A fine state of affairs. Add to that the additional landmine, sex. Much like anger, almost an opposite polarity to love.

Robin and I had endless arguments about love and sex. She was convinced that no "true" woman was capable of having sex without at least inadvertently falling in love with her sex partner. Which would theoretically make it really complicated when women became the object of sexual abuse in any way, shape, or form.

Robin had the idea that because of the duress and discomfort and fabricated internal conflict love evoked, men hated love as much as women hated sex. Which is to say, neither one of us believed that men categorically hated love and women categorically hated sex.

"Sex is easier though," she said. "Not complicated physically. Love is far more difficult. And so we get the usual disparity again. You men get what you want because it's easy. You make it easy to provide pleasure for you. We on the other hand don't get what we want because (a) it's one of those disreputable emotions, and (b) because you can't just simply undress and deliver."

The more I think about her conviction that, short of rape or prostitution, women can't have sex without falling in love, the more her behaviors and her feelings become comprehensible. Sadly, I understood everything far too late somehow, until in the end she took the concept of too late to another level entirely. But all along, we were on completely different wavelengths on all levels. I thought, for example, that when she gave me an orgasm, she got the same kind of ego gratification that I did when I gave her one (or at least thought I gave her one).

"No," she said. "It just makes me feel good to please you."

"That's what I mean," I said.

"Not quite, I think. It doesn't do anything for my ego. It doesn't feel like a major accomplishment," she said. Having danced with hundreds of women now and led thousands of ochos and boleos and even a few dozen volcadas, I think I am finally beginning to get a glimpse of what she meant. It's not a special accomplishment to give pleasure. It's, well, simply a pleasure. But, as I said before, I understand everything too late.

We had this terrible standoff once. I think the real issue was male natural promiscuity versus women's preference for monogamy. It was a really stupid situation. We weren't married yet, but we were already living together. I did my routine flirtations with women, colleagues, students, friends, waitresses, baristas. But I was smart enough (and patted myself generously on the back for it, too) to not make any overtly sexual overtures to any woman whatsoever beyond the mildly lustful admiration from a discreet distance.

One day Robin and I were day-dreaming about the future. Pure fantasies, you have to understand. She had always dreamed of living in Greece one day, and for some time now she'd fantasized about applying for a job teaching English there, convinced that one could find such a job easily. Everybody always wanted to learn English, after all.

Without her saying so, I knew of course, if it came down to it, she'd take any job, including washing dishes, if it meant otherwise fulfilling her dream. As for me, I had just managed to get my coveted tenure. I couldn't see myself teaching high-school English in Greece while jeopardizing my hard-won status at home. So I mentioned my trepidations about her living halfway around the world from my secure job that I loved. The more I brought up objections, the more vivid her fantasies became and the more or less defensively she burrowed deeper into them. I'd find Greek travel brochures and Greek university catalogs and Greek novels (Kazantzakis was the only author I recognized by name) on the coffee table, on the kitchen table, in the bathroom, everywhere. Defensive from my end now, I thought it was time to make it really clear that I was not willing to endanger my academic position and move with her to Greece on a whim. I could see it saddened her to listen to me being so adamant about not even venturing into fantasy with her, but I thought I owed it to her to be up front.

"You can always come visit me," she said. "Everybody wants to visit Greece. And sooner or later you'll have a sabbatical. What better place to spend it than in the cradle of Western civilization?"

So far I had never had the urge to be like everybody else, but, sure, visiting Greece would be no hardship. Still, I brought up more objections. What if I couldn't come visit her?

"Then I'll come visit you. And if I can't because of some inexorable responsibility on my end, then you'll just have to wait for me for three or four years."

She hissed on the "inexorable responsibility." She, incidentally, often used fifty dollar words, especially when incensed. This time she managed to make me miffed with her sophisticated language, and since miffed wasn't part of my public persona, I put on one of my guileless masks and suavely stated what I represented even to myself as the truth, nothing but the truth, broken as gently as possible.

"Of course I'll wait for you," I said. "But I'm not planning to be celibate for three or four years."

Her stunned look set off an alarm. Immediately I started back-pedaling.

"I wouldn't have any serious relationships, mind you. Just sex light from time to time."

Her face told me I had just made it worse. We'd already had it out about what I considered to be "sex light" and she persistently called "cold fucks," a term she had triumphantly gleaned from John Bradshaw. Damn the guy for betraying his own gender and making us all look bad. Robin really didn't believe that women were capable of genuinely delighting in sex light or cold fuck frolics. Every once in a while she would admit that she couldn't speak for every single woman on earth, but deep in her heart she still believed that women, all women, simply didn't treasure friendly, loveless sex light. She didn't believe in the concept of friends with benefits. "Whose benefits anyway?" was her standard line on that subject.

I admit I had the proverbial roving eye. Show me the man who doesn't. She knew all about it. It was all right with her, I thought. After all, so long as she wasn't planning to be out of the country for years at a time, I physically stayed faithful to her. It was only my eye that roved. I was wrong of course. Truth is, it was not all right with her. It hurt her terribly, but she had no defense except to accept it, much against her will.

I remember how excited I was when she mentioned a one night stand she had enjoyed, hoping I'd find arsenal for future skirmishes of sexual philosophy. And then it turned out it was simply the first night we spent together. I do remember it really was supposed to be noncommittal. At the time I thought she was much younger than I was. I don't even remember exactly when I found out that she was actually older. In any event, things between us were not supposed to go anywhere. The proverbial instance of what happens when you make other plans.

So, she had made her point about one night stands. I still kept citing the healthy, robust, and attractive girls from my college days who not only would have consensual and noncommittal sex at the drop of a hat, but who also initiated it. Robin insisted that there had been, must have been, extenuating circumstances which, seeing I was otherwise frequently clueless, I simply didn't know anything about. Probably love addiction, she surmised. Maybe past sexual abuse. Maybe even just foolish female obedience to the recent dogma of sexual freedom, young women eager to prove their mettle in the club to which they had only just lately been admitted. Back full circle to where men were sex addicts and women were love addicts. Back to her endless regret that men could get what they wanted because sex was easy, whereas women couldn't get what they wanted because love was complicated and men were too lazy to make that kind of effort and women were too well trained to please to make a fuss.

"I swear, men would rather marry or go to war, anything but learn how to love," she once said. "And most of them are dead as a result."

I really did want to be more loving. I even said the "You're all I need" line that I thought she always wanted to hear. She corrected me. "You're all I want" was what she wanted to hear, and I concede, I understand that there is a difference. I finally did say the correct words then, but it fell flat because it was too late and had to be prompted. It lacked the force of conviction it would have carried, had I gotten it right on my own.

To her, I think, the only thing that ever sounded convincing was my inopportune declaration that, were she to be absent for three or four years, I didn't plan to stay celibate. It wounded something in her so deeply that I'm not sure it ever got repaired entirely. We mended it eventually with emotional duct tape and superglue. However, I think something was permanently marred for her. Fascinating, in a tragic sort of way, to see just how fragile we human beings are emotionally.

I kept hoping against hope that I could still talk my way out of the situation. I had spent my whole life charming my way out of trouble as far as women were concerned. Plus, the fact that I was a normal lusty male didn't automatically make me an ogre. At least not in my book. Besides, I wasn't even unfaithful. I had merely projected some theoretical concerns.

In retrospect I should have simply kept my mouth shut. Unfortunately I didn't. Damage control proved to be virtually impossible. There weren't enough roses in the world to undo the damage.

On some level I suspect there was truth to what she accused me of, namely that it didn't matter so much who I had sex with, so long as I had it with someone. She couldn't bear that. She kept holding on to the idea that, if she were really special and inspiring, then I'd love her passionately and any and all conceivable detachment would go away. I would really become involved in her life, in her love, in her being. Sadly, that possibility is and was just an illusion. My male lack of emotion was a painful reality for both of us. There was nothing she could have done differently to inspire me, as she so passionately wanted to. I was paralyzed emotionally, the way I had been meticulously trained and pruned to be. In the end I don't know whose loss was greater, hers, or mine.

Robin tried to leave me that time. She took a room in a cheap bedbug infested hotel downtown -- we later referred to it as the Homeless Hotel -- possibly chosen especially to highlight to herself and to the world her abject feelings of injury. I didn't know where she was, though she'd left me a note saying that she was safe and to leave her alone.

I went by her office -- she was still teaching English at the time -- to check on her. I went furtively. I'd heard the message to stay away, and I decided my job was to politely obey. She was there. She was working. I even heard her laugh with a student. So I left again. To her, this was probably just another instance of my relentless tendency to look for the easy way out. In retrospect, I suspect she would have preferred it, had I, after a suitable amount of time, pursued her, confronted her, tried to assuage her, anything but just accept her being gone.

How it is possible, I ask myself to this day, to have loved someone so much and then to have been unable to give her what she most desired?

I did love her. I cowered in our apartment trying to persuade myself that I was doing the right thing by giving her the space she asked for. I told myself that I had done everything in my power to show her my love. And the final verdict here is, yes, I had in fact. The critical phrase here is "in my power." I wasn't yet capable of doing better. I wonder if I would do better if it happened today. I wonder if I am more evolved. I honestly don't know. I wish I could say a resounding yes.

Two weeks after she left, I found her waiting for me in my office one day. She had a key to it and had taken the bold step of letting herself in. It felt akin to a vote of confidence from one who might suspect me of withdrawing into my office with nubile graduate students to conduct sex light now that our relationship was stranded. But maybe it was just a sign of how little she cared what she might find at that point. She looked like she had lost ten pounds and her face was gray, as gray as her eyes almost. Her eyes were defiant.

"I either need to move back home or get an apartment and set a date to remove all my belongings," she said.

"Move back home," I said. "Definitely move back home."

"And if I do, I won't be disturbing any hornet's nest of non-celibate activities?" For a moment I wanted to say, no, darling, I clean up reasonably carefully after I masturbate. Fortunately I had enough wit to keep my levity to myself. "You won't," I said simply.

"I can't stand it," she said. "It's one thing to have your inclinations. It's another to feel so free to flaunt them in front of me. Am I so meaningless? The accepting little companion. Arm candy. Satellite. Intellectual sidekick. Whatever I am supposed to be to you."

Despite her moving back, for the next two years this issue kept haunting us. I still tried to find valid excuses, none of them very convincing to my sparkling adversary.

"I was tired when I said that," I told her. "It was evening. I'm not at my most lucid in the evenings."

"Exactly," she said. "So that's when you blurt out your truest feelings. I am meaningless to you. Except that you like your regular sex. And I do fine in terms of providing that, but, really, anyone would do."

"You're not just doing fine. You're extraordinary," I interjected.

She glared at me. "Whatever. The fact remains that anyone would do. It's like me and dancing. I go to these tiresome clubs week after week, and I'd love to dance with the best dancers, but seeing that I'm no longer sweet sixteen with peach skins and all, I have to dance with whoever deigns to ask me. After a while my ego gets eroded. I no longer wait, much less hope, for the best. I've learned my place. Anyone will do. The elderly gentleman who spits when he compliments me and burps with garlic sausage breath. I am grateful and charming and hope I don't make him feel like crap. But that's exactly what you do to me. You make me feel like crap, useful like toilet paper. I am not meaningful enough to be an exclusive sex partner to you. Anyone would do, really. Yes, you are grateful. Of course you are. I'm the best you can get without effort. And you don't want the best you can get without effort to dry up for you. I understand that."

"Slow down," I begged. "I'm not sure I follow you."

"It's not rocket science," she said. "Shall I repeat it from the beginning? I'll be glad to."

"So you compare me to one of your tango partners, and you say anyone would do."

"No, no, no," she screamed. "You don't understand at all. You don't want to. Let me simplify. You want sex. Any female partner will do. You're using me as a convenience because you're too lazy or incompetent or complacent to look for someone better or alternatively to make an effort to let me know that I'm the best, that I am all you want, that I am the only one you want."

"When two people love each other . . ." I never got a chance to enunciate my sentence to completion.

"When two people love each other," she hissed, cat-like. "In your book, they then simply do whatever you want and all is well, you self-righteous bastard?"

"Not exactly," I said, catching both of her wrists in one of my hands to prevent her from pummeling me or strangling me or whatever she was planning to do.

"What does love mean to you?" she yelled, her gray eyes like flint. "Just another term for your grand entitlement? Everything should fall into your lap. Because you have this fuzzy warm feeling in your heart, everybody you honor by bestowing your warm fuzzy feelings on them should then gratefully and gracefully lick your toes or other select body parts."

"I do things for you, too. I do things with you. Beyond just feeling warm fuzzy feelings," I said, biting my tongue over adding that I would gladly lick her toes or anything else if she wanted me to.

"Yeah, I read about that in a book," she said. "The prevalent male attitude: Do what I want and enjoy yourself. But God forbid you should ever consider doing something that somebody else would enjoy more than you do."

She was talking about dancing of course. Or maybe about my lack of reading her writing. Those were really the only two things she did that I didn't participate in. I know, it sounds paltry to use the word "only" here. Those were the two things that were the fire and the center of her life.

"When two people love each other, they what?" She kept bouncing up and down in front of me. "They fall into bed together because men like sex? They go to dull parties where people yak and yak and yak over cocktails and dinner because he likes hanging out and yak and yak and yak with people? Instead of dancing?"

She was relentless. "Sex is just animal nature, right? Flies fucking, and all that. But here's what happens in the animal world. When two monkeys care for each other, they groom each other. Each other, mind you. And it feels good. But here's the world according to Kevin. People aren't monkeys, after all. When two people love each other, they both groom him, his itches, his ego, and later she gets to take care of her own in her spare time."

Of course Robin was right. I did like to have my ego groomed. Vestigial ape in me. Reptile, more like. Slithering snake. Lounge lizard. That's what I have become now, dancing, a benign lounge lizard, and benign only because I no longer have any hidden objective, any calculated interest in anything besides the dance.

If I hadn't been so tightly wrapped up in my safety blankets of erudite self-righteousness (a trait which Robin frequently accused me of, though she never used the attribute erudite, at least not to my recollection), I might have listened to her more. So many days and nights (especially nights) I have now spent thinking how much I could have learned from her. She haunts me in dreams, too. Beautiful dreams, mostly, in which she sweeps through my awareness, showing me five thousand years in a second, making it clear to me somehow that for five thousand years she and her gender have studied me and my gender, voluntarily first, and out of enslaved necessity later. At first it must have been enthusiastic graciousness, until we were so pleasantly addicted to female attention that we not only took it for granted, but we also now demanded it vigorously, even violently, if by chance for a split second in the vastness of eternity we didn't receive it on a silver salver.

When I dream of her, and I do to this day, I always wake up comforted, even when the dreams peel away yet another layer of denial or dishonesty within me. "It's okay," she whispers to me in blues and purples. "You've been lied to so often, how are you supposed to sort it all out? Especially when you want to give the sources of your lies the benefit of the doubt. Mother, father, teachers, lovers, buddies. They all tell you authority, i.e. force, is love and for your own good, and they know what's good for you, after all. They tell you withholding is kindness. It prepares you and everyone else for the ubiquitous coldness of the world. They tell you feeling is anathema. It weakens you. It is reserved for women, and in women it gets despised.

The most puzzling dream she ever dreamed to me was full of green and violet, early spring flower violet. "The biggest lie," she whispered, "is this: that you have to live your life fighting, competing for resources, competing for anything at all. It will take the world a long time to shake this one. The world is addicted to your masculine concept of conflict. What conflict you've put on your competitive agenda is not nearly as glorious and as necessary as men would like to believe. You guys enjoy pain. You enjoy inflicting it; you even enjoy receiving it. In reality, it isn't necessary at all."

She bent down into my dream and kissed me. I felt reborn, fresh, cradled when I woke up from that dream. Not that I claim to understand it. But I felt it. It felt beautiful.

I almost feel apologetic writing this. As I already told you, I'm writing this for myself first of all, and then secondly for you, Tara. For a woman. Were I to write this for a male audience, I would be petrified to mention any of this. Winding words around feelings. I wouldn't dare. I'd keep it short and snappy. "Yes, sometimes I dream of Robin." Period. The end.

I made it so hard for her in our reality.

By the way, her dream of Greece eventually just withered away. Neither Robin nor I ever went, not even for a vacation.

Funny, thinking back, I always wanted to be enough for her. I wanted to be her one and only. Oh, I can hear her now. "Then we're not so different after all. I want to be all you've ever wanted. You want to be all I want."

Well, I might be flattering myself, but I do think in the end I was all she wanted. She chose me, and then she honored her own choice. If only she would have wanted me without wanting me to want her equally, we would have been in fine shape.

Arm candy? No, soul candy. I secretly wanted to hide her in our little cave of relationship, to have her all mine, forever. However, I did want the privilege of venturing out from time to time, just to window shop. What's more, I wanted there to be a little window into our cave into which my fellow men could peer to notice just what a dream partner I had here. Yes, men. I wasn't so interested in women witnessing any of this. But men -- how they would envy and admire me from a respectful distance.

Not that such a thing can ever be admitted in public. I'd be considered a traitor to my own gender.

Sometimes I fear that any admission of respect and genuine admiration for women makes a man a traitor to our gender. Traitors, of course, notoriously get scapegoated, sent into exile. A few have passed the test and made it into respectability, but only marginally so. John Keats, Rainer Maria Rilke, Pablo Neruda. A few contemporary visionaries. Me. Just kidding. I'm not a visionary. I'm a student of life. And in that role, I am also a sad failure. I know so much. But I've failed all my exams. I know everything too late to be of any use.

Like most men, I don't understand women. We end up arrogantly claiming that women simply cannot be understood. But, speaking strictly for myself, deep within myself I am mostly ashamed. I could have understood better. I simply didn't want to. I was stubborn. It was beneath me to understand a woman. Infra dignitatem.

I want to think about her all the time now. I want to keep dwelling on her. I want to dance for her. I want to bring her back that way. It isn't working.

One day she reminded me that she wanted me to yearn for her.

So I told her, "Isn't it the nature of yearning, that it's always for something we don't have?"

She gave me a puzzled look.

"That just came out of my mouth," I said. "I don't really know what it means."

"Neither do I," she said. "Interesting, though. I'll think about that."

She regularly asked me what I wanted -- presumably so as to suss out what the price of my love would be. I didn't think the price was all that high. I realize I wanted to be loved by her with all the most lyrical sentiments she could generate. I wanted to be the center of her great tenderness for life, the way I sometimes felt it in her early poetry. In a way I was hoping she could spin out tenderness after tenderness all by herself, and all toward me, without me being required to do anything to nurture it. The problem was, I couldn't tell her any of that directly.

Talk about men being the direct gender. That's just another illusion. Instead of telling her, I told her obliquely that poetry was her forte and she bravely responded that being herself was her forte. I was charmed by what I thought was a sign of insecurity overcome at last.

Oh, Robin, it's all so exhausting. You're all I want. And you're not here to hear me.

08/31/2020

05:47:46 PM