I could not, of course, have known at the time how things would turn out.

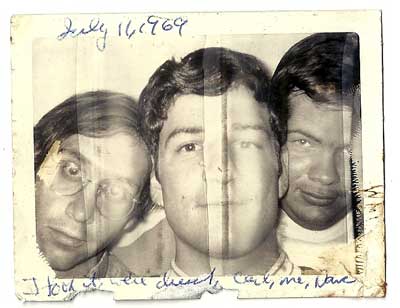

Taking the photograph was just a whim, a spontaneous act of fun after a celebratory night of drinking, snapped by a drunk young man of himself and two others, equally drunk. That the three were drunk is documented on the photo itself, we're drunk written sloppily in ink in the white margin. Also in the margin in similar handwriting of the inebriate is the date, July 11, 1969, and the subjects, Carl, me, Dave.

A memory, some say, is not a snapshot in time, it is a story we write for ourselves. Yet the picture from half a century ago is right here, and it is worth at least a thousand words.

It is small, three inches by two, black and white, and streaked vertically in several places. The photo is the product of the most inexpensive model of Polaroid camera; it was delivered from the camera with a negative that had to be carefully and smoothly peeled back from the photo itself. The jerky motions of the impaired photographer while peeling the negative away produced the streaks.

* * *

I was to be married in two days. That night, in the simplest version of a bachelor party, my two closest friends and I went out to neighborhood working class bars, having a few drinks in one and moving on to the next and then the next until, sufficiently blitzed, we returned to my apartment. Once there I thought to memorialize the evening with photography and dug out the camera my dad had given me not long before.

I gathered my buddies up from their bacchanalian repose, we stood together as near and as steadily as we could, I held the camera out in front of us with my arms extended as far as possible and took the shot.

So there we are, just our heads, Dave to my right and Carl to my left. Young men all, in our early twenties, with life's adventures before us.

* * *

Dave was to be my Best Man. Our friendship had begun at age six, nurtured by the shared experience of growing up together, Cub Scouts, sandlot baseball games, summer camp, teen aged angst, cigarettes and beer. High school ended, our friendship did not. He had gone off to college in another state and then graduate school even further away but returned for my big day.

Carl would have been my Best Man save for Dave. We met as college freshmen, became fast friends and then close friends. We explored young adulthood together, played intramural football, drank, studied, planned.

* * *

Even through our drunken haze the photo seems to hint at aspects of our personalities which unguardedly show themselves. Carl, clean shaven and hair in place, looks confident, self-assured, almost but not quite smug, with the slightest hint of a smile which suggests an impishness that is usually hidden. He appears to anticipate, to look forward to a future that he can mold and direct; a future of happiness, fulfillment, achievement.

Dave is wide-eyed behind his wire rimmed glasses, his head at a tilt, eyebrows slightly raised, his longish hair combed to the side; there is a sense of foreboding, a wondering what dilemma will next appear. There is a trace of helplessness so far as the future; he will simply have to endure it.

In the center I look at the camera, flanked by my close friends, happy in the moment and determined to go forward. Life should be fun.

* * *

Two days later, quite sober, in her back yard and under a tent, I married Gretchen, the love of my life. It was a rainy Sunday.

Dave, no longer sober now that the ceremony was over and having been able to hand me the ring I placed on my wife's finger -- his fear of disaster that he would drop or otherwise lose the ring now irrelevant -- gave a brief and heartfelt Best Man's congratulatory speech, drawing chuckles when he described me as "rejuvenated" when I first met my now wife.

Carl, kempt as usual in the white jacket and black bowtie I had chosen for male members of the wedding party, enjoyed the day, comfortably speaking with family and friends, cheering us on as bride and groom left for the honeymoon destination.

* * *

Carl and Dave, friendly but not friends, went their separate ways after the wedding. Each finished his education and went on to the next stage of life's trip.

In the early 1970s Carl was savoring life with gusto. He lived in New Orleans on Bourbon Street, drove a new Datsun 240Z, drank good wine and ate good food. He dressed stylishly as the young professional he was, training as a radiologist. On days off he sometimes nourished the passion for fishing he had developed as a boy at his family's summer cottage in rural Wisconsin by going out onto the Gulf on a small fishing charter and catching Red Snapper.

Gretchen and I traveled to New Orleans from the northeast. It was fun time with Carl and his sweetheart. Walks down the street to eat a dozen raw oysters and drink Dixie Beer, fishing, good restaurants, Mississippi River cruises, long walks through the French Quarter. Pousse-cafés. Boudin. A week-long party. Every year.

Then Carl and that sweet lady who became his wife moved to a log home on a mountainside outside of Anchorage, Alaska. He worked at the Public Health Service hospital but spent more time outside -- fishing in wild rivers, digging razor clams at low tide in Cook Inlet. Hiking, gardening, a weeklong float trip in a remote area reached by bush plane, drying food, canning salmon; he was still living life with gusto. He grew a full beard, his hair got longer, he enjoyed wearing bib overalls. The Datsun was replaced with a Toyota Land Cruiser.

Gretchen and I stopped working, flew to Seattle and took the ferry to Alaska, and that year spent most of the summer living with them. While they worked during the day we hung out, enjoying the wilderness. Evenings we four ate and drank, listened to music and talked about life, plans, hopes, ideas, and everything else. And laughed.

Dave was living in a small third-floor attic apartment in Gloucester, Massachusetts, an hour and a half from our hometown of Worcester. He supported himself with an internship in small town government in a nearby community and then working at a nonprofit agency. He dressed casually and drove an inexpensive used car. Our times with Dave never were longer than a weekend, at our place or his; quiet dinners -- sometimes lobster -- listening to him play his banjo and sing folk songs, easy conversations, just hanging out. A different sort of party, quiet and comfortable, held a few times every year.

Dave bought the house in which he lived, had the attic space extended, including a large room with big windows that afforded a wonderful view of the harbor. He was now working with his dad at their company which manufactured denim skirts. He commuted to Worcester where the production took place and often spent time in New York City's garment district showing his merchandise to buyers from large chain stores. His hair was cut short and was beginning to thin.

We still played together, happy to be carried away while he played the banjo and sang so sweetly, never tiring of the challenge of getting every bit of meat from the lobsters he steamed. One year, while Gretchen and I were doing medical residencies in Philadelphia, I was overcome with a need for lobster. Philadelphia's offerings had disappointed me and I had vowed to never again eat lobster outside of New England. I called Dave late one Friday evening and the next morning, after a night of covering the ICU, picked up Gretchen and we drove to Gloucester. A night of lobster ecstasy, cold beer, friendship and music. The next morning it was back to Philadelphia, physically and emotionally sated.

She and I then followed our dream, living a country life in rural New England. Work as a physician could be serious but life was as I always thought it should be -- fun.

* * *

Parenthood happened. We left the country life and moved to a smaller New England city. Wonderful sons with travel, sports, camping, love. Who knew fatherhood would be so great?

Parenthood happened to Carl as well. They moved back to civilization in the lower forty-eight. He obtained a position in the local HMO in the Pacific Northwest.

Dave had women in his life but never married. His denim skirt business could not compete with the flood of low-cost imports in the mid 1980's. It closed. He obtained a franchise location for a mailing, shipping, and packing business and opened in a strip mall in Gloucester.

* * *

Carl's glass was always half full. He remained optimistic, saw the best in things, continued to have many interests, remained open to new ideas. He turned in Alaska's Land Cruiser for a Mustang convertible.

Dave's glass always seemed half empty. He worried about his business even as it did well. Sensitive and empathetic, he loved to tell old stories and reminisce, but was always pessimistic about the future. He lamented the fact that he was alone even as he was certain that he had lived alone too long to be able to do otherwise. His new car was a sensible SUV chosen for the large capacity for packages he sometimes carried as part of his business.

My sweetheart and I were raising our two boys, sharing the tasks, life was still fun.

* * *

Years pass. Carl, three thousand miles away, knows our boys and they him. The distance and demands of work and family means we see each other several years apart. One year we each leave, in motorhomes, from our respective coasts and meet up for several days in Wisconsin at Carl's family's vacation cottage. Our kids play with each other. So do we adults.

Dave knows our boys from birth. He is there while they grow up; we still visit each other a few times a year. They like him; his kindness, his outspoken irreverence, his empathy with the tribulations of growing up. They remain exceedingly fond of him even when they have become adults.

* * *

Carl becomes infirm, his health progressively deteriorating over a couple of decades. Travel for him becomes impossible. In 2007, Gretchen and I spend a month on a meandering mini-motorhome vacation, crossing the country and visit again. Still a party even if in a muted form. Beginning in 2009 I fly yearly to visit him. His death several years later is not unexpected, a few months after my final visit; a handshake and, "Thanks for everything, Carl," the final farewell. A friend for 52 years.

Dave has some health issues but overall does okay. He continues to work in his business daily but no longer has the emotional energy to travel. He no longer plays the banjo. I make it a point to visit him every spring. We spend a comfortable evening each year, reminiscing, laughing, and just talking. On his 60th birthday in November Gretchen and I blow up a number of balloons, write on them Dave's milestone age, and drive to his business in Gloucester. We walk in without warning, surprising Dave, spreading the balloons everywhere. A few weeks later on Gretchen's birthday she receives a large box in the mail. It is filled with the balloons, still inflated, we had left with Dave.

Dave and I speak on the phone once or twice a month. We have a pleasant telephone conversation just a couple of weeks before his unexpected death a year and a half after Carl's; there is no chance for a final farewell. A friend for 65 years.

My life continues. Retirement, perfect grandchildren, my sweetie and I still in love. Life has been fun as I have always thought it should be.

* * *

I now know how things turned out. The photo was for decades inside a photograph album and never seen. It now is held on a wall at home by a pushpin.

Best suggests the singular, one above all others, but I was so very fortunate to have two best friends. Carl and Dave were quite unlike one another but if forced to say one and not the other was my best friend I could not do so.

When I look at the photo, that snapshot in time of three young men, I think that if one believes in destiny then perhaps we each fulfilled ours. Life's adventure really has been in some measure a party; as with any party, no matter how terrific, eventually the people leave and go home.

Originally appeared in Red Coyote.

11/30/2020

02:20:03 PM