From the Desk of Sir Hilary Tocherty

My Dear Charlotte,

If I were a Papist like the people down in Tocherty village I would be speaking to a priest about this matter. It is testament to the barbarity of that religion that the priest would undoubtedly grant me absolution in return for the rattling of some beads. I do not deserve absolution. I certainly do not deserve a place in the Kingdom of Heaven and dare not ask for one.

These papers shall be my confession but they are a confession only to you, my sweet Charlotte. I do not write them in the hope that you will forgive me for the crimes you cannot yet imagine. I only wish to explain the circumstances of my own death that you will not, in mourning me, expend too much of your energies.

I mean this tale not to be a melodrama such as those by Collins and other such charlatans. They are, with their nonsense tales of ghostly creatures waiting on roads to meet unsuspecting travellers designed to appeal to the baser instincts of man. They are best left as the fare of foolish schoolboys. I enjoyed such tales myself in my time as all youths do but have no desire for my own tale to join their ranks.

I believe, however, that I must begin with the most salient fact of the case which will necessarily press my story into their company.

I have spent much of my life haunted. By haunted I do not mean in the metaphorical sense and nor do I mean that Tocherty House is in the nature of some kind of modern day Castle of Udolpho. I mean that I individually am haunted and plagued by the most devilish of apparitions.

Perhaps if it had first appeared to me at a younger age I would have told my mother or the nanny in expectation of comfort but when I first saw it I was past ten years of age and home for the summer from school. Ten years old, it seems to me, is the age at which a young boy becomes a young man and no young man wishes to be known as the kind to call on his mother to soothe his childish fears.

I had been in bed for some time but the oppressive and unusual June heat had made my rooms uncomfortably warm and I found myself unable to sleep. I had the candle lit at my bedside and was propped up against my pillows. I was reading something which, though I don't remember the title, was undoubtedly of the quality and subject matter of the aforementioned melodramas. In fact, before hard experience disabused me of the notion, I had believed that exposure to those very melodramas was the source of the apparition.

I had opened my windows wide, a practice deplored by my mother as likely to give me a cold, and my curtains were twitching slightly in the breeze. That same breeze was causing my candle to flicker, the effect of which was that I was forced to squint in order to see the text before me.

Such squinting, along with the late hour, was wearisome to the eyes and so I put the book down for a moment to rest them. My skin was covered in an uncomfortable layer of sweat which I wiped from my face with my hand. It was then that I heard her voice for the first time.

"Father!"

In all the years I saw the terrifying creature, she only uttered one word. She spoke in a tone so wheedling and searching that it made the heart reach out to her in pity. She sounded like a lost thing. So much so that my initial reaction was not to look around the room but to look out of the windows, my mind leaping to the possibility of a child, perhaps having wandered away from Tocherty Village, roaming the dark fields outside in vain search for her parent.

"Father!"

There was no doubt that this second call came from within the room. My heart beating fast, I looked about widely, biting back a scream which would bring the shame of having my mother come running. For a moment there was nothing there.

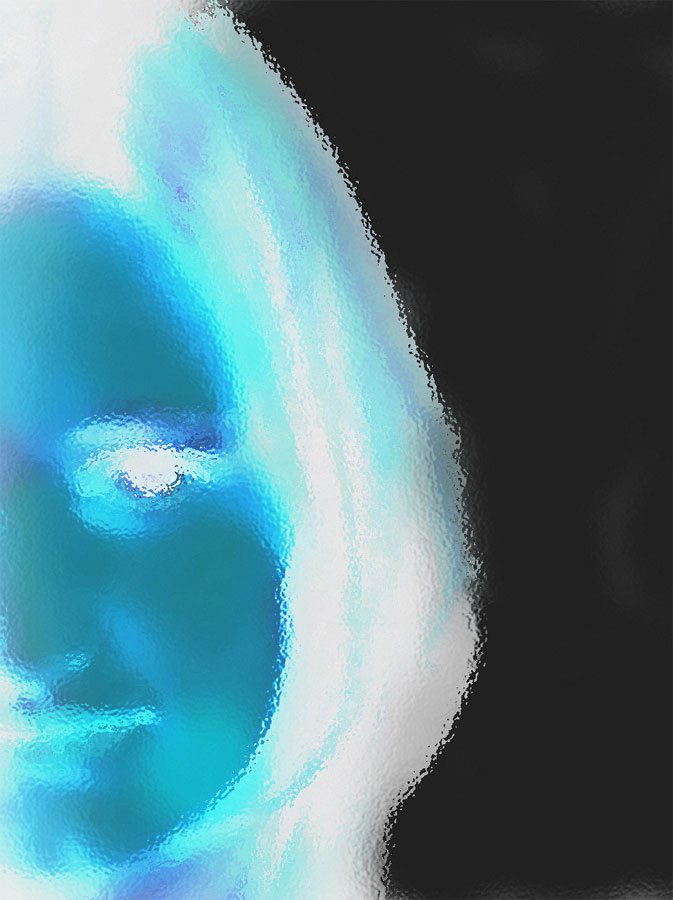

Then I saw her. She looked the same as she would my whole life. She was the palest creature you could imagine with no touch of colour in her skin or hair. Even her eyes were pure white, gazing sightlessly and frighteningly at my own face. Her delicate hands tore ceaselessly at that colourless hair and she paced in small circles, taking small silent steps.

I blush to mention this but she wore nothing at all. As naked as that day she was born, if indeed such creatures were born at all, she stood before me. The hair above the most secret of places was as colourless as that on her head and her small breasts sat atop the unmistakable curved stomach which indicates that a woman is with child. I need go into no more detail.

As I lay there in my bed that night holding back the screams which threatened to overwhelm me, I truly thought that the time had come for me to meet the Lord God above. For this creature, I was sure, could be nothing other than the angel of death herself, here to drag me from the Earthly realm. The truth of the matter was that a small part of me hoped this was the case. It was the only way I could envisage the end of the fear that so gripped my soul.

She looked towards me and stretched out one pale hand, an accusing finger pointed. I remained on the bed, frozen in place, unable to look away.

"Father!" She whispered again and darted forward without warning until she seemed to be at the foot of my bed. I pushed myself as far away as I could, pressing myself against the wooden headboard and scraping at it with my nails as if I could by brute strength tunnel my way through the wall to safety. I could look at that deathly gaze no longer and, to my shame, screwed my eyes shirt like a bairn trying to wish away a nightmare. I closed my mouth as tightly as my eyes, holding my breath within as if by doing so I could make myself invisible and invulnerable to her devilish power.

I sat that way for what felt like an age but could not have been above five and twenty seconds. When I opened my eyes I did so bit by bit, the better to close them again if she still stood where she had before. At length I was sure I was alone and opened my eyes fully, allowing them to adjust to the dim light of my candle. She was gone and I was alone.

Yet, I caught flicker of some movement around the spot where she had stood and my heart began to flutter again until I realised that it was but the mirror, a large, ornate, ugly thing. I threw it away some years ago but in those days it sat to the right of the door in my bedroom. It stood in fact, exactly where I had seen the terrifying apparition.

This fact had not occurred to me when I was faced with the terror but now that I was alone, and starting to feel somewhat foolish, I understood what had happened. I had been reading, an activity which always tires the eyes, and that along with the dim light and the late hour caused me to fall asleep whereupon I had the awful nightmare from which I had just woken up. The mirror, reflecting myself, had only served to reinforce the idea that there was another in the room.

I gave what I hoped was a knowing, adult chuckle at myself. I closed my book and placed it on the bedside table then I picked up the candlestick and brought the flame near my lips, feeling the tickle of warmth. I kept a close watch on my reflection in the mirror, despite my outward bravado, and blew out the flame.

Immediately the apparition reappeared. I uttered a choked yelp, almost dropped the candlestick. Looking away from that pale devil I snatched a match from the bedside table with numb fingers, struck it on the wood of that same table in a manner which would have earned me a clip round the ear from my mother if she was to see me treat her furniture so, and hurriedly lit the flame.

When the candle flame was lit I saw that there was nothing there at all. There was only my own pale face reflected in the mirror's darkly polished surface. This time I could not raise a laugh but endeavoured to look at the matter from a scientific perspective.

At school I had, as I am sure many children had both then and now, been involved in certain late night games with my peers, the aim of which was to scare one another witless as far as possible. One such game was that of Mary Worth. The story went that Mary Worth had been trapped by an evil witch within a mirror and said, furthermore, that she could be summoned by standing before a mirror with a candle in hand and repeating her name no less than thirteen times. Whereupon she would appear, covered in blood, to kill whoever tore her from her natural world.

The other boys and I would scare ourselves silly with this game, which invariably ended with leaving us all squealing in half-pretended fright until the matron would come into the room to skelp us all for being awake.

The reason this game was so frightening was that the longer you stared into the mirror, the more distorted and shadowed your face became. Perhaps, I reasoned as I lay in my bed that night recovering from my fright, this was due to some deficiencies in the mirror itself or else some process of the brain the likes of which my father read about in his magazines.

I decided that this must be the explanation for what I saw that night. There was no woman at all. Neither was there a nightmare. It was only my own reflection staring back at me, distorted by the shadows and the candlelight. I smiled at myself but my smile was uneasy. Even then I was not convinced by my own argument. Still, it served to allow me to sleep for the night, though I left the candle lit and dozed off to the sound of the guttering flame.

I saw no more of the apparition in the following months. Indeed it was not until November of that year that I experienced another visitation. Yes, my sweet Charlotte, you see my ordeal was not over. It is not even over now though I hope that this night will end it once and for all.

For the second visitation I was back at school. It was once again night and I was sound asleep in my bed when the ferocious rattle of the wind against the window woke me. I stared at the dark ceiling for a moment, confused in my half-sleeping state. The snores and sounds of the other boys in my dormitory had a comforting familiarity and I would perhaps have fallen back asleep unmolested had I not heard a sharp crack at the window as if a stone had hit it.

I sat up in bed listening to the rain outside and, hearing no further recurrence of the noise, felt brave enough to investigate. I slipped from under the blankets and walked over to the window on the cold wooden floor. As I approached the window I could see nothing from it except for the dim shadows of the branches of the trees outside thrown into relief now and then when the half moon in the sky was unobscured by clouds. Then, without warning, I saw her.

I had thought of the apparition only occasionally since her first appearance. Most of these times had been when I was lightly in the grip of sleep, when the shadows on the wall seem to creep towards young boys and every gust of wind sounds like a banshee's scream. When I saw her again in front of the window that night all of the feelings from the first incident were brought back tenfold and I stumbled back from the window, clamping my hand over my mouth in horror.

She was in the same pose as before, pacing back and forth with one hand plucking at the hair on her head. The light of the moon streaming through the window had the effect of increasing her translucence. I could see the frame of the window through her rounded belly.

"Father!" she called softly. I felt cold at the sound of that whining voice and wrapped my arms about myself, shivering in fear. I looked about the other sleeping forms in the room thinking that surely one of them would be awakened by her call. Not one boy stirred.

Once again she looked towards me with her milky gaze and once again she darted forward, her arms outstretched as if she meant to snatch me. This time I could not hold my fear within myself. I stumbled away from her and cried out for help. My heel hit a trunk sitting at the end of one of the beds and I tumbled head over heels, still screaming.

This outrageous noise was enough to rouse my classmates and the room was soon filled with their own shouts of alarm. The apparition seemed to hear this noise, looked at me closely with those blind eyes and then, without a sound, she was gone and I was left alone on the floor listening to my classmates and the inevitable stomp of the matron's feet as she came to see what the bother was.

This began what was to be a difficult time for me. When the room was properly lit and it was discovered that I was the one screaming, it was also discovered that I had urinated on myself. I say this with no shame now because I remember well the terrible fear that sight elicited within me but my classmates were not so kind.

Their teasing was cruel and relentless but I bore it as best I could until the end of term. Unfortunately, the Christmas break did nothing to lessen their teasing. In the end I put a stop to it by adopting a policy of fighting anyone who dared mention it. I was a big lad even then and, though I lost a few of the fights, I soon made my point and the other boys moved on to someone else.

The second cause of my difficulties was more significant. The apparition now seemed fixed upon me. I thought of her as a ghost or a bogle but unlike these creatures she was not tethered to any one location. She did not wander the empty halls of a castle or drift about a graveyard at dusk. Instead she was wherever I was. It was I who was haunted.

Any time I passed a reflective surface when the sun was down I was sure to see her looking out at me with those horrifying white eyes. She never smiled or winked or made any expression and, whenever I saw her, I tried to hurry away before her helpless wail for her father reached my ears. The sound of her voice was the most horrible thing of all; it slipped into the ears like poison and infected the mind.

I grew thin and wan and developed a deathly fear of mirrors and windows and metal, and anything else in which my own reflection could be seen. I banished them from my rooms, removing them myself to avoid the necessity of uncomfortable conversations with my parents. I told nobody at all of my affliction, but I attended the kirk with a constancy which bemused my father and delighted my mother.

In the kirk I prayed for only one thing -- deliverance from this devil. My prayers were not answered. I became convinced of the heretical notion that she was a being far beyond the power and will of the Almighty. With this in mind I even tried heathen practices to rid myself of her. On my braver nights I would bring a mirror into my bedroom and then wait in the dark with only a small candle lit until she inevitably appeared, pregnant and calling for her parent.

When she did so I would snatch up the small rosary I had procured in secret from the Catholic church in Tocherty and splash her with the small vial of holy water I had taken from the same. I tried this three or four times over the first year of her visitations to no avail. She regarded those tokens with indifference. Indeed, they caused no change in her behaviour at all. If she was a demon as I believed she might be, she was of the most powerful and uncommon type.

If I gazed at a mirror for long enough she would dart at me like an animal moving towards its prey but the fright caused by these sudden lunges was the closest she ever came to harming me. Her features were frightening but she could not be accused of undue ferocity. The prevailing impression she gave me was, as the months passed and I began to get over the fright at seeing her, that of pity. She was a lost thing, whether her desperate calls of 'father' were for her own or for that of the child she carried.

Around a year after her first appearance I was used to her in that strange way in which one can get used to almost any ailment. I still preferred to sleep in a room with no mirrors and with the curtains drawn but this was as much for the purposes of having a sleep uninterrupted by her cries as it was any real fright. She occupied my thoughts often, however, even on those nights when she did not disturb me.

When I was feeling particularly brave, for even though I now believed that the apparition could not or would not harm me, her visage still occasionally brought about a twinge of fear. I would sit in a darkened room with the shutters closed at midday, staring into a mirror. She would always appear, pale and pregnant, and begin her restless pacing and calls. On some of these occasions I would try to speak with her to see if my words could penetrate the veil beyond which she stood.

I would ask her name and ask if I could help her in any way. I would read Bible verses and ask if she was a creature of God. I even began to tell her things about myself, rambling stories about my terms at school or my friends. She did not respond to anything I said. She did not even stop her ceaseless cries for her parent or the unborn child's. Her high pitched cries would interrupt me until I grew tired of our one sided conversation and threw open the shutters to let in the bright afternoon sunlight whereupon she would immediately vanish.

She also vanished if anybody else happened to look towards her. On several occasions the housekeeper or my mother opened the door to a room in which I was trying to converse with her and found me sitting quite alone in the dark, staring into the surface of a mirror. My mother scolded me on those occasions not, I could see even then, because I had truly committed any particular transgression but because my manner and behaviour on these occasions scared her quite badly. Perhaps she thought me mad or perhaps she thought it was some strange game of the sort often played by children.

Of course I could tell nobody about her. I saw that quite plainly. The only outcome of doing so would be to convince everybody that I had quite lost my mind. Indeed, I have never told anyone about my affliction until now and only do so because I know that scandalous stories will soon lose their power over me. I hope, though do not request, that you, my dear Charlotte, will not be quick to share this tale for reasons which will become apparent very soon indeed.

The years passed and that dreadful apparition became so common to me that I found the sight of her from the corner of my eye when I happened to pass a window almost a comfort at times. In a very real sense I grew up with this ghostly, distressed creature and, though she never once responded to my various attempts at communication, I grew almost to like her. Indeed, there was at times more than that.

I hesitate to disclose what follows, my Charlotte. The Catholics, pagans though they are, believe that absolution can come only from the complete disclosure of sins. I am no Catholic and you are no priest but these are, it seems, the roles we must play to each other. Thus I will tell you all and if any of it offends then you may allow your eyes to fall down the page until the narrative takes up a subject that is at least slightly more palatable to you.

Growing boys often experience pangs of lust for any convenient object within their reach. To do so is no real sin, I believe. If it were then it would hardly be as universal. Over my time at school I had peers confess to me their arousal at the sight of a busty maid, the thick-legged matron, a rosy cheeked older cousin, even their own sisters through stolen glances through cracks in the boudoir door. There was an energetic trade in erotic drawings, some torn from gentlemen's magazines, some drawn by the more artistic boys. All showed ladies in various states of undress to satisfy carnal lusts.

I had no need of such facsimiles for every time I chose to look in a mirror at night I was treated to the sight of a young lady in a state of undress. It must disgust you, my Charlotte, to read this but there was many a night when I spilled my youthful seed at the sight of her brazen nakedness, her plump breasts and the tantalising thatch of hair above her sex. Even her pregnancy was not enough to deter me. Rather, either through repeated exposure or by natural inclination, it only increased my ardour. As it is only you who will read this, my Charlotte, I blush only a little to recall your own pregnancy and how that event increased my nocturnal visits with you.

It is now that I must move to that part of my tale which concerns you most directly, my Charlotte. I pray but dare not hope that you can find it within yourself to forgive me for what you are about to read.

After I left school I went on to Oxford and then to India where I spent a happy four years directing the natives in various building projects. It was good work for the benefit of a culture so much beneath our own in wealth and knowledge and I returned to Scotland with a newly prideful step.

I had wondered, though I was no longer afraid enough to pray for it, whether the apparition would leave my perception as I sailed to new lands but she followed me wherever I went. In mirrors and windows and silver, even in lakes and streams, I would see her restless pacing and hear her desperate cry. There were days when, feeling sick with longing for home in the unfamiliar smells and sounds of the Eastern continent, her calls of 'father' were a comfort to me and helped to ease me to sleep.

By the time I returned to Tocherty I was four and twenty and had wholly accepted the apparition's place in my life as immutable. This was to change soon after you became my wife. When you visited Tocherty that fine summer after I returned home, I had no expectation of romantic feeling. One doesn't when one hears that one's younger, distant, cousin is coming for a visit but when I saw your beauty and heard the sweet sound of your voice I knew that you must be mine. I think, I hope, that you felt the same. In any case, you accepted readily and we were married.

It was only a month later when you told me the most joyous news of my life. You were with child and I was to be a father. I remember this conversation clearly not because it was a happy moment, though it was, but because it was the moment that marked when mirrors once again became just that. I passed mirrors and windows at night and paused, expecting the familiar sight of her pacing and calling but there was nothing. The apparition was gone and remained gone for over fifteen years.

I believed, not without cause, that her disappearance was a reflection of my newfound happiness. Perhaps her presence had always been a reflection of my own yearning for the true love that I found in my union with you. I puzzled on the subject for many months until the arrival of our daughter pushed all thoughts of anything else from my mind.

I have not, as this document attests, been a blameless human being but I truly believe that there was never a more devoted father to a daughter than I was to our little Emma. Her every whim was my command and I delighted in the imperiousness she developed as she realised this. You scolded me often for spoiling her but I could do nothing else. She was my whole life and I loved her beyond what I could have imagined.

There was no space for any consideration beyond her loveliness and so the thoughts of the woman in the mirrors faded until they seemed to be merely a story which happened to some other person. Indeed, the memories of her were so fanciful that I became half convinced that I had seen nothing at all and had merely dreamed the terror that visited me each night in my youth.

You and I grew older, my dear Charlotte, and so did Emma. It seemed impossible how quickly she moved from being barely more than a babe, running about the flagstone floors on her sturdy little legs and half driving you and the nannies mad with fear that she would fall and injure herself, to a comely young woman of fifteen.

And my, but she did look so much like you at that age, my Charlotte. Her hair was not the honey-blonde of vulgar shepherd's girls in romantic poetry but so pale as to almost be white and her cheeks glowed red with any strong emotion, be it pleasure or embarrassment. Her languages and her painting were exquisite, but it was her music which delighted me the most. When she sang in her sweet, high voice, accompanying herself on the piano in the drawing room, I felt compelled to stop and listen. The sounds lifted my heart and warmed my soul.

Every visitor to the house agreed on this point and young men like Mr McGregor, fresh from the colonies and Mr Menzies of Aberdeen had only to visit for but a moment before they fell as completely in love with her as I did. Emma for her part delighted in our parties as much as our visitors delighted in her. You and I hoped that her match would be found soon, remember, and we had already at her tender age began to have pleasant thoughts of grandchildren.

It was after one of these aforementioned parties that the greatest tragedy of my own life occurred. I must tell it now. I must. I am compelled to. "'Twere well it were done quickly" if indeed it must be done.

It was hogmanay and the revels were ended. Our guests, your brother and his wife, the McGregors, the Wringhims, had all retired for the night. You had retired too, reminding me not to remain up until too late an hour.

The food had been finished before midnight and we had been in the drawing room for drinks and cards. That was finished too and all that remained was the smell of alcohol and the ringing memories of the laughter and jokes of the preceding hours. Only a few of the candles remained burning and Emma and I were alone.

It was the kind of evening which might have seemed Gothic and frightening were it not for the fun which preceded it. The room was gloomy and I sat back in my favourite chair with a glass of cognac. Emma sat by the piano where she had played some Burns in the hours before. Now the sounds of these songs had faded and I felt their absence. Emma looked out of the window and I saw her face half reflected back at me, the expression thoughtful.

"My dear," I said, getting to my feet. I shall admit that I swayed slightly as I did so, "Perhaps you would oblige me by playing a final song before we retire."

She turned from the window and smiled at me, her face beautiful in the flickering candlelight.

"Of course Papa," she said obligingly. She set her hands and began to play a song I soon identified as one of Gow's -- his Lament for his Second Wife which she knew to be one of my favourites. I set my glass on the piano and watched the liquid within tremble with Emma's every gentle touch of the keys.

I felt the burn of the whisky within me and sat unsteadily on the bench beside Emma. She did not stop playing but turned to smile at me. My heart melted at her loveliness. My beautiful girl. I leaned to kiss her cheek chastely but as I did so she moved her face again and my lips alighted on her own. Perhaps it was this, perhaps it was the whisky or the way she looked so much like you. Perhaps it was all of these things but I found myself unable to remove my lips from hers and I wrapped my arms around her firmly, pulling her to me.

The music stopped.

I find myself unable to commit to paper what happened then, my Charlotte, though I know that you will already have guessed the end of my sorry tale now. As I write there are tears running down my cheeks and my sensibilities flee from what I know lies at the end of that night of which I speak. Just know Charlotte, my dear Charlotte, that she did not come to me willingly. She did not surrender her honour -- for surely some blame would be hers if she had. Rather, I wrested it from her like a beast and sullied that holiest of pearls in such a way that would cause even the de'il himself to look away for shame.

Much of what happened next you already know. I secluded myself in my work and avoided even mealtimes so that I should not need to look upon our dear daughter. It was a great pain to my soul that I robbed myself of my greatest joy in life by giving in to my lowest impulses. I took my meals in my study and saw others only when strictly necessary.

I did not work as I claimed however; much of my time was spent staring out of my window at Tocherty Catholic Church down below, trying not to meet the ghostly reflections of my own eyes.

Emma began, it seemed, to waste away but this only made her shame more apparent when it started to show. It was, of course, you who noticed it first my dear. At first you weren't sure that you were correct in your assumption -- she simply seemed to you to be slightly rounder in the belly. When this roundness began to increase even as her limbs became thinner than ever, you became certain.

You will remember coming to me in my study and sitting on the small chair by the fire where, when you yourself were big with child, you had often liked to sit with your sewing while I worked. I was brought forcibly back to these happier times when I turned to you and asked you what was wrong.

Your tears and your bewilderment as you told me the whole sorry tale broke my heart. I crossed the room to kneel before you, took your shaking hands in mine and told you the only thing I could think to say. I told you it would all be all right. I knew, though, that it could not be.

I had been completely ignorant of the change in our daughter's physique over the previous weeks owing to my avoidance of her presence and I was horrified at the realisation. A dark part of my mind whispered that a girl who would seduce her father so may well do the same to any man. The child need not be mine. I knew in my soul though, as surely as I know there is a God above, that the child of my child was mine. A greater abomination has surely never been dreamt of outside of hell itself.

You looked at me with tear-streaked eyes, "We must call her in. We must ask how this came to be," you said.

I bit my lip. I could think of no reason to deny your request and so, ringing the bell for the help, I had one of the maids fetch Emma from her rooms.

She came in meekly, knocking first and then entering with her eyes downcast. It was clear that she knew what it was we had called her to discuss. She gave me a flickering glance and the terror and confusion in her eyes was like a blow.

I knew what I must say -- you were looking at me, expecting rightly that I would lead the way in this matter. When I did speak I did so at only the barest of levels above a whisper. Perhaps you took my low voice to be reflective of my anger or disgust, or even to avoid being overheard by the staff. In fact I spoke so because I could hardly bring myself to utter the words at all, so afraid was I of being exposed as the most wretched of creatures.

"Emma it is the belief of your mother and I that you ..." I sighed, "that you are with child."

She raised her head then and looked me directly in the eyes. I am proud to say that I resisted the temptation to try and communicate to her a threat to enforce her silence. Instead, I tried my level best to show her from my expression that, should she choose to tell you what we did, I would accept it.

She paused, seeming to choose her words carefully. When she finally spoke she was looking only at me and ignoring you entirely though we could both hear your gentle sobs breaking the silence.

"This is true, Papa. I am sorry but it is true." A few tears appeared at her eyes and trickled down her cheeks. Her cheeks were flushed a dark red and her hands were clutching at her hair close to her scalp.

"Who?" You yelled, losing your composure, "Who has done this to you?"

She looked at you with pity in her eyes. The moment before she answered seemed to stretch to eternity. I held my breath, visions of how my life could change moving before my eyes, "I do not know," Emma said finally and fled from the room, weeping.

You moved to follow her, but I caught your arm, afraid that any more questioning would bring the truth to light. "Leave her," I whispered in your ear, wrapping my arms around you, "I will talk to her later when she is calm,"

You perhaps turned to me to argue the point but the sight of the tears in my eyes melted your resolve and you wept in my arms until I took you to bed and left you there, the curtains drawn, to contemplate alone what had happened to your daughter.

When I left you I went upstairs to Emma's rooms. I knocked before I entered and, at her quite bidding I opened the door and stepped inside, closing us both within. With a quick turn of the wrist I turned the key in the lock to keep the servants out, remembering that her maid had altogether too much familiarity with her and the tendency to burst into any room she happened to be within.

As the lock clicked into place Emma spoke, "We must tell her," she said.

I whirled around, my heart pounding. Emma was sitting on the window-seat, her legs brought up to her chin in a pose which reminded me of her all too recent girlhood. The heavy flush was still present on her cheeks and now that her mother was not there, her eyes were bright with fury. It was the first time I had been alone with her since what happened and I shrank from that anger.

"What?" I could scarcely believe my ears. Did she mean to tear our family apart in this way?

"Mother must be told," she insisted, "I can't live with this secret, Papa," perhaps unconsciously she caressed the slight bump which even I could now see was beginning to show just beneath the swell of her breasts. I flushed and felt quite ill at the memories of what had happened. How could this be? I could see why God had seen fit to punish me, but why punish Emma? It seemed designed to twist the knife in my guts.

I stepped towards her slowly, spreading my hands in what I hoped was a calming gesture. She looked at me with a fear that cut my heart like a sliver of glass and I stopped a few feet short of her window seat. She uncurled herself and got to her feet. Face contorted with effort, she crossed the distance between us and stood close to me. I could smell her perfume. It smelled like roses. I should think that if I were to smell roses now I would be rendered quite insensible. If I had any intention of seeing summer, I would order the bushes in our gardens pulled up before they have a chance to bloom. As it is, it hardly matters of course.

"Papa we must," she aid quietly. "Who else must I accuse? Am I to sully another innocent name to keep our secret? And who shall it be? Which one of our friends should I blame?" I knew she was right and she must have seen so in my face for she pressed on, "So you see we must tell mother. We must tell her together."

With this said she put her hand to my cheek as she so often used to. However, as she did so I noticed a slight contortion of her face and was stricken to realise the meaning of this expression. She was disgusted by me. To touch me disgusted her so much that she was unable to hide the expression on her face.

I made my decision quickly then. It was the obvious one to make. Emma was absolutely correct that there was nothing to be done but to tell you what had happened, but what kind of life would that be for me? Shamed and friendless, alone in the world and shunned by my neighbours. The sight of Emma's disgust was the final blow. Her face was so much like yours that it seemed a dark promise as to how you would look at me when you found out. I couldn't live with it. I pushed Emma to the side and made my way to the window, meaning to leap out.

Emma pursued me, crying for help, and pulled at my shoulder. I pushed her away again, more firmly and threw open the window to let in the early spring air. I heard the sound of the birds in the glen and savoured it, pleased that the final sounds I would hear would be so beautiful. Then I stood up on the window-seat Emma had so recently vacated and prepared to jump.

"Father, no!" Emma screamed. I felt a hand on my coat tails pull me back and I stumbled from the window-seat, grabbing for any handhold available to keep my balance. My flailing hand struck Emma's back and, with no purchase, I fell heavily on my rear. Propelled by my accidental push, Emma was forced a few steps forward. Her legs hit the window seat and she overbalanced. She fell out of the window so silently that for a moment all I could do was sit on the floor, mouth agape. The crunch as she hit the ground below was loud. It sounded like a nut cracking.

That night I sat alone in my study in silence. You had been given a sleeping draught by the doctor and were in an uneasy slumber, your body exhausted after so many hours of begging God to give our daughter back the life I told you she deliberately took. The doctor had given me a vial of the same drug and had advised me to take it. I had not yet. It sat on my desk beside my papers and an empty ink bottle, waiting for me.

I knew I could not give in to the temptation of a dreamless sleep. I was living my own nightmare and it was well deserved. A relentless masochism forced me to remain awake, playing the moment of Emma's death over and over again in my mind. The silence followed by the crunch.

Though I knew I had not had any intention of harming her, I knew too that, however inadvertently, I was the cause of her death. This thought was almost unbearable but one thought kept me from attempting again that same dark act was the thought of you, my dear. To lose one member of the family was enough, I thought.

By and by I dozed off without the draught, exhausted by the events of the day. I have no way of being sure how long I slept but it cannot have been more than an hour. When I woke up, I was no longer alone. Emma stood beside the full length mirror on the opposite wall.

I stood up with a cry which caught in my throat as I reached out to touch her. So desperate was I to feel her skin on mine again that I did not stop to consider the impossibility of her being there. I froze in place, however, when I realised that she was naked as the day she was born. Her stomach curved softly beneath her breasts, betraying the child within, and I could see the light patch of the hair between her legs. One hand caressed that bump while the other tore in agitation at her hair.

"Father!" She cried and looked at me with milky eyes devoid of sight.

It was her -- the bogle from my youth. And yet it was Emma. I realised then, sinking to my knees with the weight of the knowledge that she had always been my Emma. Some deeds, it seems, are so obscene that they reverberate through time like a sinful echo. She had haunted me even then for a crime I was yet to commit. She had been gone while Emma was alive but now her life had been so cruelly snatched from her she was back.

"Father!" She called again. I moaned and reached out to her, unable to work up the strength to get to my feet and wrap my arms around her. I knew, though, that I never could. I had often tried to touch her as a young man; no matter how close you got she always seemed the same distance away like a rainbow. Except of course when she saw fit to dart at me.

As if reading my thoughts, Emma or the demon who had taken her form ran at me, her sightless eyes staring, her hands clutching at air. Forgetting in that moment, that the shade was harmless, I let out a hoarse scream and scrambled back until my back hit my desk. I reached up and scrabbled at the surface until my hand alighted on a glass paperweight. I clutched at this and threw it with all my might. The paperweight flew through Emma's blank face and crashed into the mirror behind her. It shattered and with a final "Father," she was gone, leaving me alone on the floor of my study, weeping in confusion and fear.

So you understand now why I write this, sitting in that same study twenty-four hours later. You are, my Charlotte, once again in a drugged sleep and I am alone. Alone with Emma. You see, when I began this confession, I set up the small vanity mirror from your boudoir, and as the wee hours of the morning approached, she joined me in the room. I can see her in the mirror, standing behind me naked and blind. She has said nothing as I wrote. I know why. She is waiting. She has always been waiting for me. Calling for me.

I took all the laudanum ten minutes ago. The doctor gave us enough for four more draughts each. I took it all at once and already I can feel it working. It will be a peaceful death, I think. More peaceful than I deserve.

The question that haunts me, my Charlotte, is this. The church teaches that we are judged by the Almighty on our actions. So why, then, did He see fit to begin my punishment before I committed the crime itself? Was I always to do so? Or was Emma's appearance in my youth a warning I did not heed?

I must stop writing soon before the final sleep takes me. My confession is almost complete. I say again, Charlotte, that I confess not in hope of your forgiveness. In hope, perhaps, of your understanding instead. Understanding of what I have done and what I am about to do. I love you Charlotte, and I am sorry.

I must confess one final thing before I cease. I confess that I am afraid. I am not afraid of death, as you may imagine, nor of the hell that surely awaits me. No, I am afraid that, as the laudanum takes me and I lay my head on the cool wood of my desk, I will see those horrifying blank eyes flash in the mirror beside me and I will hear her whisper "Father," in my ear.

I pray to God to grant me that she not do so. I pray, my Charlotte, that He give me this last request. No matter what I have done and no matter what awaits me in the next life I do not want that ghostly, searching, accusing voice to be the last thing I hear.

I do not want to die screaming.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.