Mercy Masawi stood in the potholed street before the Prince and Polish Car Wash, balancing a wicker basket on her head. In the basket were a few bananas -- now showing black spots from the sun -- a box of Madison cigarettes from which she sold singles, and bags of popcorn and salted peanuts. A scrap of scarlet cotton she had salvaged from a storm drain after a rainy season downpour cushioned the weight of the basket.

Charles Chihuri, the owner of the car wash -- or proprietor, as he liked to call himself -- lumbered toward her from the shade of a mahogany, coming into the brilliant sunlight, which glistened off his shaved head. He was a broad-shouldered man whose belly overhung his cowhide belt. His nose was flat, his nostrils flared. Today he was wearing a white shirt, gray trousers that sported the sharp creases of prestige, and crocodile skin, square-toed lace-ups.

“How are you today, my sister?” he said.

He was so close now that Mercy could smell the syrupy sweetness of the African Cream Spirits he had been drinking from under a bough of the mahogany.

“May God save us,” she said.

Charles smiled. “He's Zimbabwe's only hope,” he said, adding, “how's business?”

“I'm struggling, sir,” she said. Strapped to her back by a large towel, the towel's corners knotted together around her waist and under her arms, was a child, bubbles of snot issuing from the child's nostrils.

“You've got two children?” Charles asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“The other one is in school?”

“Grade one. But the school fees. Uniforms ... I'm struggling.”

Charles grinned.

“I pray every day, sir.”

“Have faith, my sister,” he said.

Charles stepped closer still, so close that she didn't want anyone to see him next to her. It was indecent, his nearness. She thought of the men she walked past every day who said, “Look at that stick there!” Or, “She's too weak to fetch a bucket of well water!” Or worse, “She can be had for a dollar, I'm sure.” These slurs were often followed by childish giggles or drunken laughter. The fathers of her two children had been no different. The second man, after a night of drinking, had punched her in the eye when she'd asked him why he was returning home so late. And yet she still dropped to her knees every night and prayed that one day God would deliver to her a good man.

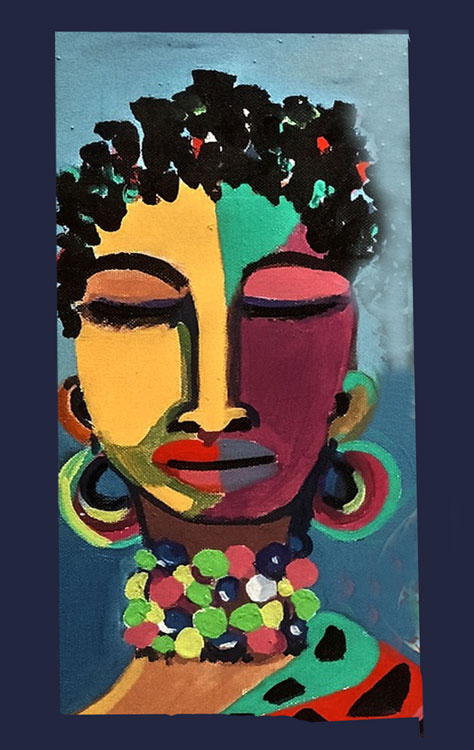

Mercy walked with an erect carriage. Her nose was slender, her skin as black as onyx and just as lustrous. On those few occasions when she had the time to look at herself in the broken mirror of her room, she thought she was as beautiful as an African princess. But when she walked along the streets, seeing other women with baskets on their heads hawking what she did, all of them struggling to get by, doubts about her beauty plagued her; perhaps she was just as ordinary as they were.

Charles said, “Why don't we go for a drive this Sunday morning in my Benz?”

Mercy turned, looking at his white Mercedes-Benz Kompressor parked in a corner of the car wash. Maybe one of the doors was the color of primer paint and the rear window was cracked, but it was a Benz; she'd never ridden in a car that only the rich owned.

“A Benz will make you feel special,” Charles said.

She replied, “But what will your wife say?”

“What I do is none of her business,” Charles said. “Give me a Madison.”

Mercy looked away from him, down the dusty, potholed street, and watched a troop of gray, black-faced vervet monkeys cross it; most climbed a eucalyptus tree. The large male remained perched on a rickety fence guarding a dilapidated Rhodesian-era house that had a rusty metal roof and cracked windows. The male scratched his chest and showed his canine teeth before chasing a female up the trunk of the eucalyptus and out onto a limb that bent down under their weight and snapped back up again when they continued on to the roof of the house and over its peak, out of sight.

“My Madison?” Charles said.

Mercy thought of the musty room she lived in with her two children. It had one small window, through which gray light entered. A naked light bulb hung from the ceiling, but she could rarely afford electricity. She cooked on a hearth behind her landlady's house using firewood that she gathered in the mountains. The smoke often burned her eyes and made her choke. The toilet was behind the house, too, as was the red brick building that served as a place to bathe from a plastic bucket of well-water.

“The cigarette,” Charles said.

Mercy lifted the basket from her head, and Charles took the box of cigarettes and removed a Madison and struck a match and lit it, blowing the smoke in her face. He paid her. She now had enough money to feed herself and her children tonight, a bowl of maize meal, some tomatoes and kovo cooked in a dab of oil.

“We'll drive past every church in town,” Charles said, “right when services are over.”

“They'll laugh at me,” Mercy said. “Everyone laughs at me.”

“Do I?”

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.