It was an entire month before Hotoli could articulate, to her twin sister Botoli, or even to herself, why moving to their new house, deeper into the city centre of Rajahmundry, made her feel so uncomfortable. Not in any startling way, but in a more chronic, diffused sort of way.

She was relieved to have moved away from the rural belt of Andhra, where cement homes were an anomaly amid dense foliage. Besides, the new house, like their old home, stood along the banks of the pythonic Godavari River, so there was a sense of continuity, but only in an intellectual sort of way. She didn’t feel it viscerally – in her limbs, her belly, her gut. It wasn’t about feeling culturally out of place either; the sisters, originally from a faraway hilly region, now in their 50s, had been living in South India for four decades. There was something else. It became clear to her one morning while bathing.

Hotoli was standing under the shower, scrubbing herself between her legs as the water pounded her head from above. In their old home, where they collected bath water in a bucket, she would squat on the bathroom floor and clean the open folds of her vagina with one hand, while liberally throwing mugs of water on it with the other. It was an intimate cleansing ritual that left her with a sense of complete control. Though the water available to her was finite, she had more agency over how she used it. Now, the gushing flow above her head was oppressive in a way that took her farther away from her own body. She couldn’t bring the water, despite its abundance, to her crevices while standing like that, and never felt clean enough.

When she mentioned this to her sister over dinner one night, her profound epiphany was met with loud, witchy cackles. Botoli, the more practical of the two, had no time for such shallow concerns and was more preoccupied with household matters, like fumigating the new place and, more importantly, procuring the right meat for their meals, for the kitchen was her department. She was deeply interested in sourcing the finest, healthiest and most tender meat and cooking it right. She always used historically approved combinations of spices, herbs and roots – ginger and bamboo went with only some types of meat, garlic and mustard were used only if the dish was cooked a certain way, turmeric and ghost chili were used during some seasons only… all these intricate recipes and rules, carefully curated and preserved by Botoli, were lost on Hotoli; her palate wasn’t nuanced enough to receive these flavours in all their aboriginal glory. When she was hungry, she ate whatever was prepared.

It wasn’t just culinary disinterest that kept her out of the kitchen. Hotoli couldn’t stomach the gore of the cleaning process – all the blood, bones, cartilage, muscle, organs, skin… she’d rather encounter the animal for the first time as a fully cooked meal on her plate, not as dead flesh in the kitchen sink. But this was hardly a point of conflict for the two. Like most duos do over long periods of cohabiting, they too had found a rhythm around their insipid existence. She made up for her squeamishness by doing the dishes.

Even to look at, Hotoli and Botoli were ordinary. There was nothing wrong with the way they looked, but they belonged to the proverbial audience; the spotlight never found them. Still, there was something reassuring about them, like there is about all ordinary people, things and occurrences. While gazing at the likes of them, an onlooker’s mind is instantly reassured that everything is as it should be – regular, normal, plain, ordinary, medium… snugly nestled in the middle of statistical safety. Pleasing as they are to behold, extremely attractive or wildly talented people, just like very rare events, are disconcerting, because they tend to jolt you away from the crowded average and fling you towards the lonelier, more dangerous fringes of the bell curve.

For Hotoli and Botoli, the press of ordinary living was comforting. The spell broke only when their well-oiled routine was disturbed, by unwelcome neighbours, guests, sometimes well-meaning strangers. They kept to themselves and didn’t take kindly to these interruptions by “other people” as their long dead mother used to say, in her characteristic nasal voice that became pronounced during arguments. For her, as for them, this applied to everyone who wasn’t immediate family; even friends and distant relatives were mercilessly othered by her. Now that all manner of close family was either deceased or estranged, the twins operated as a self-sufficient, insular unit, with no ties to anybody else. They never held regular jobs; their mid-sized inheritance was always enough to meet their daily expenses and spare them the horror of meeting other people every day.

This kind of asocial life came more naturally to Botoli. Even as a child, she preferred spending time by herself or with her sister. Once, a classmate told her she had dreamt of her the night before. Botoli, just six at the time, came home howling, because she felt being cast in someone else’s dream without her permission, with no control over the film that played out in that person’s head, was an unacceptable invasion of her privacy. She never spoke to that girl again and concluded that “others” were a breed best kept at bay. Hotoli’s experiences while growing up were not that extreme, but as they entered adulthood, they fell in sync and inherited their mother’s dislike for people in general, with effortless passion.

Neither sister had taken a lover in over two decades. Given their isolation from the outside world, level of interdependence, constant companionship, and division of labour around the house, they were almost spousal in their spinsterhood. They didn’t feel the need to let anyone into their dreary domestic bat-cave, a space where time moved in a slow, dull loop, almost like it were a third, catatonic entity in their midst.

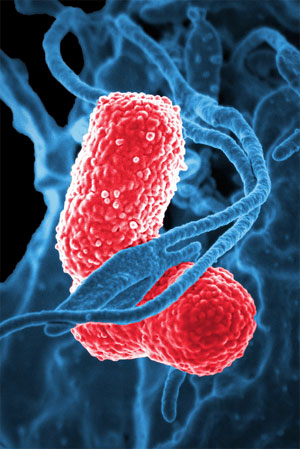

The more romantically disposed of the two, Hotoli thought about intimacy sometimes. On idle afternoons, after she was done cleaning the tough grease off the utensils they used for lunch, when she lay on their sofa in her post-meal torpor, she mused about what being with a man would feel like after all those years. The bacteria on her body, she surmised, would be overwhelmed by the sudden burst of alien flora and fauna native to her lover’s skin, tongue, breath… it was microscopic, but that’s what it came down to, Hotoli knew. Making love, she thought, was the coming together of not two human bodies but the billions of invisible creatures, indigenous to each lover’s mucous membranes.

Sometimes she amused herself by imagining what it would feel like to have magical vision that magnified all the microbial life on the surface of her skin, scalp and hair, and watch as it moved around in its own ecosystem, at a pace much faster than the reality she and her sister had created for themselves in that house.

One evening, as Hotoli was in the middle of one such idiosyncratic daydream, Botoli walked in on her, a large bag of wet meat in her hand, and asked her what she was thinking about, sitting motionless like that on their rocking chair, dressed in her favourite blue nightgown. She didn’t want to say, “I just imagined a squishy green worm sliding between the gap in your front teeth,” so she simply shrugged and smiled, glancing at the plastic bag, grateful she didn’t have to help with the skinning.

Though their days and nights were all alike, Hotoli was occasionally subversive. Sometimes she let her creative urges leak out of a crack in their daily routine and spill all over their timetable. Barely a fortnight after they moved into this place, she sat up all night painting the walls. She picked a shade of off-white that looked very similar to the original colour of the walls, but painted over every inch anyway. She missed her morning chores and Botoli was upset with her for an entire week, her mood mirrored in the food she prepared… chewy, under-cooked, under-spiced and rubbery.

Another time – this was in their old house – Hotoli decided to try some sort of macabre village art she’d read about in an old book about ancient tribal paintings. It involved melting a bowl of sugar and using it instead of paint on a blank white canvas, then leaving it out in the open for a while and stepping back as ants crawled onto the canvas, giving shape to the strokes, morphing it into artwork that is alive. Finally, a transparent plastic sheet was placed on top of this monstrosity, trapping the writhing, swarming mass of insects underneath it. This experiment really irritated Botoli not just because of its inherent morbidity, but also because it derailed that day’s routine by several hours. She refused to carry that ‘painting’ to their new house. The final image was of a disproportionate buffalo that looked as dead as the black bugs that gave it shape.

Though she didn’t express it, Hotoli was very affected each time her sister got angry. Till the passive aggression between them subsided, she felt trapped inside her own cranium and jailed behind her own ribcage. The house either felt like a sanctuary or an asylum, depending on the quality of their relationship.

They usually resolved their fights over meals, cooked by Botoli with special care. When she felt she had punished Hotoli enough for something and wanted to dispel the unpleasantness between them, she made soft, perfectly roasted meat, garnished with a blend of condiments she seemed to save for such occasions.

One such morning, after a week of silence between them, Botoli stood on their veranda, looking at the eastern bank of the river. The water looked choppy and dirty. Deciding to end the fight that day, she idly watched a family of four walk along the road that ran parallel to the river. Soon, more people gathered around them and it was hard to keep track of that family. Then, Hotoli woke up and joined her, matching her gaze to look at the people below. As she stood next to her sister, she sensed the tension of the last few days dissipate. She placed a hand around Botoli’s shoulder.

The morning sun was getting brighter by the minute and the two squinted as they looked at the scene below. From that height – it was the fifth floor, but felt higher, somehow – the river, the road and the junction at the end of the lane looked like an enlarged map of some kind, not an actual place with real people and vehicles passing through it.

“I was thinking about what you told me about the shower,” Botoli said.

“Yes, please buy a bucket on your way back from the market today. I need to change the way I bathe. I feel filthy all the time,” Hotoli said.

“Okay,” Botoli said, lifting a cupped palm above her forehead to shield her eyes from the sunlight. “There’s a hardware shop very close to the butcher’s gully. I’ll get your bucket from there… Also, I’ll cook something special today – there’s a discount on leg pieces this week. Let’s get someone chubby for a change, similar to that dark one there,” she said, pointing to an obese, middle-aged woman, in a yellow ‘half saree’, an attire that teenage girls in that region usually wore. It was odd to see it on a fully grown woman. She had stopped walking momentarily to pluck a pebble out of the sole of her chappals, the fat around her tummy moving as she leaned forward.

Hotoli nodded, with a hungry smile, feeling a rush of saliva in her mouth. She had skipped dinner the previous night. It was impossible to eat when harmony eluded them. “We haven’t had juicy cellulite in a while, anyway.”

“I’d better leave before the market gets too crowded,” Botoli said, ruffling her twin’s hair affectionately. She hummed as she gathered her purse and draped her overused red and purple cotton shawl, that belonged to their mother. She left.

Hotoli stood there, staring at the road that was waking up in earnest now. More cycle-rickshaws and pedestrians kept appearing, making that part of the East Godavari District resemble just about any busy, semi-urban street, anywhere in India. She spotted Botoli stepping onto the footpath, making her way through the mass of people going about their morning errands. Within seconds, she disappeared and became one with the crowd.

A cloud appeared out of nowhere and covered the sun, taking the sting out of Hotoli’s eyes. Only a narrow ray of light washed over her, as she stood there surrounded by countless motes of dust apparently suspended in eternity.

Originally appeared in Lit 202.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.