The cop stopped his patrol car behind a big red ambulance and let the dispatcher know he’d arrived. He thought about waiting for his partner, but 419’s were typically routine calls. Write a report, get the deputy coroner here, maybe he and his partner would get their lunch hour on time. As he exited the patrol car, distant thunder turned his attention to dark and gray clouds crawling over the mountains and into the valley, like a tidal wave of gloom coming to flood the city. Not that he wanted the gloom, but the rain would be a much-needed break from over 200 days of drought.

Pausing on the curb, he glanced at the stuccoed four-plex, just as a pair of EMT’s exited the plain brown door of unit 1B. They walked quietly, with their heads down, carrying heavy bags of medical equipment. One of them mumbled from under a walrus moustache to the cop as they passed, “Brooks and Murk, unit 549, we arrived at 1610 hours. It’s a natural.”

“Thanks,” the cop said and scratched their information down in a pocket memo book. This didn’t mean much to the cop. Most 419’s were just that … natural. The elderly or terminally ill passing on. An administrative duty for the cop unless something was found that warranted a detective.

Sagebrush hopped around the small gravel yard. Wild weeds grew from cracks in the oil stained driveway. He stepped over a kid's bicycle to reach the front door. It quietly opened before he could knock. A middle-aged Mexican woman greeted him with a smile forced by politeness. She wore a stained gray sweatshirt. Mascara smeared from her heavy and sad eyes. “Hi ma’am, police department,” the cop said.

She stood aside, letting him enter a cluttered living room adjoined to an even more cluttered kitchen. The blinds were turned down, the lights off. The only illumination came from prayer candles lit all around the small living room and kitchen. The long, tubular types, decorated with faithful saints he thought looked like stained-glass windows. His police radio burst to life with a traffic unit calling in a car stop just off the interstate. He reached around the back of his belt and turned the volume down.

The cop noticed there was no hospice nurse and the familiar smell of the elderly he expected was not present. There was no hospital bed or medical equipment, no Tupperware container full of the prescription meds the nurse or the family always gathered. He turned and looked at the woman, about to ask her about this when loud thunder boomed outside, like a bomb detonating. It startled both of them. The angry rumble that followed lightly vibrated framed pictures of a young man and woman with a baby. The walls and windows shook as the noise carried through the small complex of townhomes, causing the cop and the woman to make awkward eye contact. It was then that he noticed the woman in the picture wasn’t the woman with him now.

A clunky refrigerator magnet from the Grand Canyon displayed crayon art, and a report card with a smiley face in red ink. There was no sign of the sick or old here, just a happy and normal family, and this made the cop think back to the words the EMT uttered as he passed, “…it’s a natural.” The woman forced another smile and said, “He’s back here,” then motioned for him to follow. She led him down a small hallway, lit only by a Batman nightlight shining outside the bathroom. The walls were lined with more pictures of the same woman and young boy. She stopped at a door that was ajar halfway down the hall. She faced him, tears filled her eyes. He heard the muffled rhythm of prayers and uncontrollable wailing in a closed bedroom at the end of the hallway.

“Who else is here? Who’s crying?” He motioned over her shoulder to the sounds of the weeping. She opened her mouth to speak, but couldn’t. The cop saw this and instead of waiting for her words, opened the door and entered.

A boy lay on the carpet in the middle of the room. He was six or seven years old and at first glance resembled a child-sized mannequin you’d expect to see behind glass at the mall. This boy was dead.

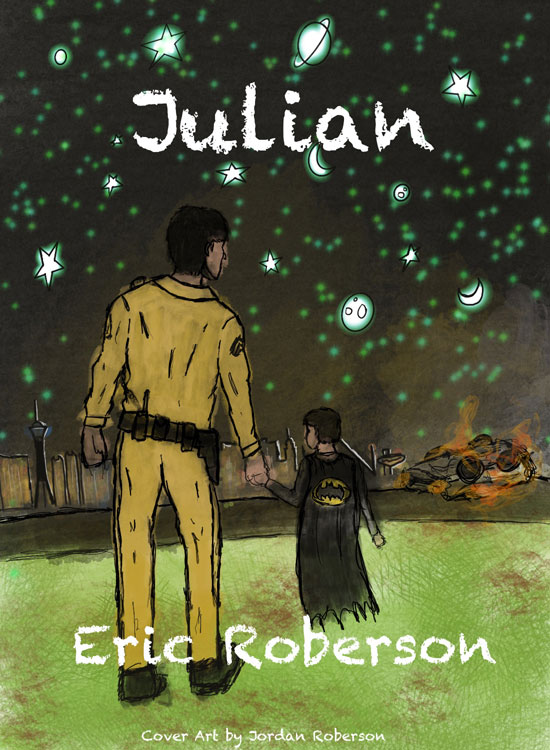

The boy wore Batman pajama bottoms that lay loose around his small and sunken waist. His skin was a soft bluish hue, his little eyes were half open and fixed on the popcorn-textured ceiling above, where someone-probably his mother had placed small glow-in-the-dark plastic moons, planets, and stars. Probably to help him fall asleep, the cop thought, even though he didn’t have kids himself.

The cop couldn’t take his eyes off the boy. His lips, frozen in what he thought was a whisper of some sort, were purple and caked with an orangish syrupy liquid that dried as it oozed down the side of his mouth. Empty plastic medical packages and two pair of latex gloves littered the area around the body. A half full bottle of children’s liquid ibuprofen lay in a pool of its contents near the boy’s head.

He knelt to get a closer look at the boy. No bruising, nothing to indicate strangulation, no petechiae, nothing that could help the cop make sense of this. Nothing that immediately answered “the why” every cop was trained to chase down. And then a sinking, heavy feeling in his chest. The cop thought he recognized the boy. A deafening stillness took over the room and a pang of uneasiness stabbed at the cop’s senses. He had visited an elementary school two weeks earlier. A class full of second graders. They crawled through his police car and tugged at his uniform. One boy … this boy, he thought, never left his side and asked the cop everything about his job. He remembered talking to his girlfriend about the boy:

“This kid really clung to me. Stayed by my side the whole day,” he told her later over happy hour. “Wouldn’t let me go.”

“Maybe he saw something in you. Something he’s missing,” she said, picking green olives out of her Martini and plopping them in her mouth.

“He asked if he could go on a ride-along with me.”

“Well?”

“He’s a kid, a second grader, of course he can’t go on a ride-along,” he said, amused. “He grabbed my hand a couple of times and would say, let’s go chase bad guys. Take me with you to chase bad guys.”

“Who knew you were so good with kids,” she said. “I think it’s sweet you had such an impact on a little boy. You’re going to make a great father one day.” She winked over her Martini as she sipped and then smiled at him.

419, the radio code for a dead body, is routine in the cop’s world. Death is a regular part of the shift, but nothing about what lay on the floor in front of the cop looked or felt natural. Rain began pelting the bedroom window. The cop heard soft sniffles behind him. The woman spoke between bouts of crying and trying to catch her breath.

“His name is Julian,” the woman said. “His mom said he had a low fever last night. She gave him medicine before he went to bed. This morning she yelled for him to get out of bed to get ready for school. After a few minutes, he didn’t answer … she came in and found him in the bed. He wasn’t breathing, he was cold. She called 911… she called me; I’m her sister. I live around the corner.” Her voice began to pitch higher while she fought to speak, “I rushed over here and found them in here … she had pulled Julian out of bed … she was trying to give him medicine … and was praying and crying for him to wake –” She began to sob. The cop looked over at the half full bottle of ibuprofen, and the thought of his mother trying to pour it into the boy’s mouth felt like an ice pick in his chest.

“I’m sorry, but we need to leave this room,” the cop said as he stood. He escorted her into the dimly lit hallway and into the room with her sister and mother. He stammered condolences to the boy’s mom, unable to make eye contact, her pain too much for him, “I’m sorry for your loss, ma’am. We need to stay out of his room until the deputy coroner arrives for –”

“A police officer visited Julian’s classroom a few weeks ago.” The mother grabbed his hand. “He was so excited when he came home. He wouldn’t shut up about being a cop when he grows up,” Julian’s mother said between sniffles. She squeezed his hand so that he would look at her. She wore a black robe with golden stars all over, her long auburn colored hair hastily pinned to the top of her head. Tears smeared through just-applied eye liner and blush. Not the beaming and happy face the cop recognized from the pictures. She hugged the cop and this somehow made it more … personal. Something a cop shouldn’t feel on a 419. Now he knew Julian. Had talked to her son about how much fun it was to drive fast with lights and sirens on. Had promised to one day take him to catch bad guys, and told him what he needed to do to be a cop when he grew up. The cop awkwardly embraced her, “Don’t leave my baby in there all alone, please don’t leave him alone.”

“I won’t,” was all he choked out as she pulled back from him and closed the bedroom door, leaving a dark wet stain on his tan uniform shirt. The cop retrieved his phone from a pouch on his belt and called his partner, who had small children.

“Don’t come here,” he said, “You don’t need to come here. It’s a little boy and you just don’t need to be here. I can handle this.” His partner thanked him and said he would make it up to him for sparing the sight of a dead kid.

“His name is Julian,” he said to his partner.

The cop called for the deputy coroner over his police radio. He went back into the room to be with Julian until the deputy coroner arrived. Alone with the boy, his eyes were drawn to his face. His purple caked lips, those eyes … barely opened to the plastic stars and what lay beyond. There was a silence in the room so quiet it hurt his ears. He tried to concentrate his eyes on the boy’s toy box, on the scattered clothes and action figures strewn about, just like his own room when he was the same age. But he couldn’t keep his eyes off the boy and he surprised himself when he suddenly gasped with a choking cry. He covered his mouth and turned to face the window and the angry rain outside. In a few short seconds the cop swallowed the emotion, choking it down like a big, fat, grainy vitamin that goes down sideways.

But then a sound, very faint, like a whisper. “I’m sorry you can’t be in here,” the cop spun around, but no one was there. He looked at the door. Closed, just like he’d left it. He heard it again, this time in his head. Like the softest of whispers pinging in surround sound between air pods in his head. He looked at the body. The whispers stopped. Julian lay there, lips parted, lifeless. $

The cop watched the deputy coroner examine the boy’s body. He was methodical and thorough. The deputy coroner had a red-pitted nose and his belly hung over his belt. He had an accent and the manners of a southerner. The cop listened while he gently explained to the family that Julian’s body would be handled with the upmost dignity and taken to a facility where he would be further examined, and then moved to a funeral home of their choice. But the cop knew the boy would be placed in a cold plastic bag and lie with strangers in a cooler, until it was Julian’s turn to be opened and emptied, to find out what caused him to stop being … Julian.

Later, as the cop was getting into his patrol car, the deputy coroner stopped him, “How long you got on the job, young man?”

“Two years next month,” he answered, “why? Did I mess something up?”

“No boy, listen here. Sometimes …” he drawled and stared up at the dark clouds. “Sometimes … kids don’t look both ways before they cross the street,” he said, like a coach easing a player through losing a game. “Sometimes a parent beats on a kid too hard, or a stray bullet finds’em, or sometimes they go to bed sick … and what God gave’m to fight it off just ain’t … well, it just ain’t enough. Stop trying to make sense of this,” he said, and patted the cop on the shoulder then waddled off through shallow puddles to the plain white panel van with black windows that contained Julian.

The cop sat in his patrol car. He watched the steady rain dot the windshield and felt relieved to be out of the townhouse. He radioed dispatch that he was available and scanned the mobile dispatch laptop for a call that he could wrap his head around. Something with blades and gory gashes. Bloody gunshot wounds, a 2,000-pound car and a broken pedestrian. Death made sense when these things happened, but not this. “Sometimes,” he said, mimicking a southern accent, “… is too fucking often!” He put the patrol car in gear and drove away. For the rest of his shift, through driving sheets of rain, the cop thought of Julian. $

The rain stayed in the valley through the cop’s days off. He looked at a picture of his nephew on the fridge, a gap in his innocent smile, messy hair and wearing a soccer uniform. He thought about calling his sister and asking about him, but she would say, “Settle down, get married, your nephew needs a cousin.”

He thought about inviting his girlfriend over, but she would see something was wrong and would want to talk. He would have to tell her about Julian. He didn’t want to talk and he certainly didn’t want to be around people. The cop replayed the words of the deputy coroner over and over in his head while he drank Jack Daniels from the bottle, “Sometimes…” He fell asleep to the sound of the storm and the fat leaves of a cottonwood scratching at his bedroom window.

The scratching soon turned to whispers and the cop’s eyes jerked open. Julian stood next to his bed. His shiny blue skinny body and Batman pajamas reflected in the lightning. A flesh colored zipper stretched from his collar bone down his chest to his abdomen. He smiled at the cop and drank from an ibuprofen bottle, the shimmering medicine spilling down his face.

“I keep drinking this stuff but it doesn’t make me feel any better,” he said and smiled, then reached for the cop’s hand.

The cop shot up from his pillow. Covered in sweat and panting, he looked around the room. He was alone. He put his hands to his ears, closed his eyes and concentrated hard. No whispers. He looked to the window. The rain had stopped and the leaves from the cottonwood hung dripping. He got out of bed and went to a drawer where eight weeks ago he’d stashed away half a pack of Marlboro Reds.

The cop slipped into a cotton robe and then into his backyard. He fought hard to keep his mind off the boy and decided he would skip the squad BBQ the next day. His partner and other cops’ families would be there, and his girlfriend would squeeze his hand tight every time a kid did something funny or cute. His partner would ask him about the 419 and he didn’t want to talk about Julian. The cop didn’t want to see or hear their kids having fun, running and swimming, and laughing.

He lit a cigarette and took a long pull, letting the hot smoke fill his lungs. He tilted his head back and closed his eyes. His head fluttered from the nicotine sabbatical. He beckoned for himself to be present, to clear his mind. His head still back, he exhaled slowly and invited himself to the here … and the now. He opened his eyes just in time to see the stars and the moon peek out from the clouds. $

“Three-victor-33, shots fired! Shots fired!” The cop’s radio shouted as he smashed the accelerator to the floor of the patrol car. The engine roared in response under him. Red and amber lights bounced off his reflection in the windshield and the roads that looked shiny and new from the passing storms. The sirens screamed and bellowed warnings in various pitches as the cop carefully maneuvered through traffic.

The cop knew he was only a few blocks from his partner. He reached down to grab his radio mic to let dispatch know when it dropped from his hand. The cop’s eyes looked down to pick it up. When he looked back up there was a kid in the road, eyes wide, mouth open and frozen in a scream that couldn’t be heard. He swerved the wheel and missed the kid. Tires screeched and the patrol car flipped and rolled… asphalt – stars – asphalt – stars – asphalt – stars …

BLACKNESS

The cop slowly came to. He began to take inventory of himself and opened his eyes to a hazy light so bright it hurt his brain and caused him to squint. No sirens in the distance, no sounds of traffic, no screams for help. The air around him was electric and he felt disoriented and dizzy. A familiar deafening silence filled his ears. The cop looked up through the haze, he squinted trying to focus his eyes, slowly he began to make out little glow-in-the-dark plastic stars … planets … and a moon glued to a popcorn-textured ceiling. He heard a familiar giggle and looked over to see Julian, with his zippered chest and Batman pajamas, sitting next to him.

Julian slid his cold hand into the cop’s. He leaned in and whispered, “I thought you’d never get here.” His orange, ibuprofen-stained lips and teeth smiled warmly as he gestured towards the light.

“Let’s go.”

09/22/2023

09:14:54 AM