Congden crossed the airlock threshold and adjusted her sky blue lab coat with the self-consciousness of a new employee. She welcomed this slight nervousness, however, as the next step in her renewal. Poor souls by the millions had not been so fortunate.

Harsh sterilization fumes faded as she and her guide traversed the lobby of the research center. Neon letters above double sets of glass doors grew larger as they approached. Congden slowed to read them while her companion kept going, his gaze fixed upon his cell phone.

HUMAN REGEN, INC.

WE REBUILD BODIES.

WE REBUILD LIVES.

YOU NAME THE BODY PART.

WE REPLACE IT.

“Except the brain, right?” Congden said.

Her guide slowed and partially turned, brows raised. “What’s that?”

Congden did a little jog to catch up while pointing. “... replace body parts -- except the brain.”

“Oh that,” he said, as someone who encountered the slogan so often as to ignore it. “Partial brain augmentation is totally legit.” He gazed at her with a mix of sympathy and weariness. “Up to forty percent.”

“Really? I didn’t hear mention of it when I was interviewing, or read it on the new internet. I figured it wasn’t feasible or something.”

“We don’t really market it because our return on investment is so low. That may change with Dr. Bender’s latest invention, Neural Interface Scaffolding. NIS is still experimental and highly confidential -- but since you’re starting in the brain lab, I figure you need to know.”

“Sounds interesting!” Congden said, and meant it. “But why stop at forty percent? I mean, there’s got to be plenty of veterans and civilians injured in the war who are in need.”

Congden’s guide for her first day on the job was a slightly disheveled man in his late-30's from the People department. In her excitement at landing the lab assistant gig in a war-torn economy, she’d forgotten his name. She leaned forward to peek at his identification badge but couldn’t make it out without being obvious.

Her guide shook his head. “We’re swamped with war casualties, for sure. But the ‘in need’ part gets sketchy with brain requests. The allure is a sort of immortality, hopping from one body host to the next, supplanting the host’s original brain along the way. It’s murder, really, unless the host is already dead. And even Dr. Bender can’t bring someone back to life.”

Congden grimaced, a hand straying to a scar on her jaw. “One life is plenty.”

“Agreed,” he said. “And in the brain organoids we’ve used for partial augmentation, impulse control can be an issue. There are no social standards with a dish-grown brain.”

“But the brain organoids grown here aren’t true brains, right?” she said. “I mean, no has done that yet.”

Her guide returned to his phone and waved for her to come along. “Not the size of what’s in our skulls right now, but not insignificant either. There are morality issues. Do we grow a brain long enough for it to become sentient? Consciously aware of its surroundings and itself? Bottom line is we can legally augment an existing brain for a max of forty percent. More than that risks a takeover.”

“That doesn’t sound good.”

“It can be quite undesirable.”

Congden’s gaze settled on the murals painted on the walls.

Portrayed there was a boy missing a lower leg, a woman with an eye patch, a cop without an arm, a soldier in need of both legs and an arm. Along individual timelines, each met with doctors holding medical cases adorned with the letters HRI. The subjects converged on a hospital and exited, resuming their individual time lines ... as rebuilt people.

Rendered complete. Not with prosthetics, but with biological body parts. Almost as if the injury or defect had never occurred; biologically whole.

The mural people stood on new fleshy legs, even walked and jogged. They threw balls, shot basketballs, planted trees and flowers, walked behind grass mowers, picked up and carried children ... with new fleshy arms. The woman discarded her eyepatch and smiled from a mountain overlook, admiring the view with now two lovely eyes.

“Amazing,” Congden said, slowing to take it all in as they approached the double doors.

“We do important work. So many casualties with the war, even with this latest truce. These murals don’t even portray the organ replacements we perform -- hard to pull that off artistically.”

Voices carried to them from the far side of the lobby, along with metal clanging. Two workers were moving and fastening together large pieces of a temporary stage. Another worker manipulated light stands and paused to take meter readings. Indoor plants stood in a cluster nearby, waiting for positioning around the stage.

Her guide preempted her question.

“You probably noticed the thick security outside. Ambassador Lievhan from the Global Peoples Alliance is visiting in a few days. Our government wants us to share our bio-regeneration knowledge as a peace offering. The GPA would like to help their people the way we are helping ours.”

Congden’s expression darkened. “The enemy should keep to their own damn country.”

Her guide’s eyes widened at the menace in her voice. “Yeah, but the war did enough damage to all countries. The cease fire is hanging by threads and prayers. Maybe this will help build an official treaty between our nations.”

“GPA bullets and bombs made me an orphan. And more.”

“Sorry. I lost my wife during the Raleigh Offensive, but I’m ready for enduring peace.”

Congden made the sign of the cross and looked up to heaven. “May they rest in peace.”

He nodded somberly, raised his phone with a slew of text messages. “I keep up with my kids on the phone. Schools just started up again last year. I’m sure you know that with your own studies.”

White coats with gold trim pockets appeared on the other side of the glass employee entrance. People guy pressed a button and held it so the doors remained open a moment more than necessary to let them pass. “Thank you, doctors.”

The two white coats strode through with curt nods. They glanced at the attractive new research lab technician as they passed.

People guy let go of the button and the doors closed and locked with a sharp metallic click. He spoke over his shoulder while thumbing through his text messages. “Research scientists. They spend a lot of time in our surgical center, and analyzing and running models on computers. They’ll send orders to your Clinical Lab Tech for experiments and results. Your role is to assist the lab tech in performing those tasks.”

He sent a reply on his cell. The slight smile that formed while he texted faded quickly. “It’s probably obvious that the research scientists are our heavy hitters. They drive the business, though with the war we’re always backlogged. ”

He swiped his badge in front of the reader and the door unlocked. He nodded inward to Congden. They took a few steps and then her guide stopped and held up a hand.

“Hey, I should have let you try your badge. Would you stand back and let the door lock, then try it?”

“Sure,” Congden said, this time getting a good look at his badge. Vincent Bartlett.

Her badge worked and they started down the hall, where they encountered intersecting halls and the first glass panes of laboratories. A rigid man in his late twenties appeared in the intersection of two hallways and stood impassively before them. His green scrubs hung loosely but without a wrinkle.

Bartlett pulled up and gestured. “This is Osman Phelps, Clinical Lab Tech. He’ll be your supervisor in the neuro labs.”

“Background check complete?” Phelps said to Bartlett.

“Alicia is cleared,” Bartlett confirmed.

“Awesome.” Phelps turned to Congden. “So you’re the new RLT.”

“That’s what they tell me,” Congden said, summoning a nervous smile. “Research Lab Tech.”

“Chasing a doctorate degree now that colleges are open again?”

“Uh huh. Biology.”

“So far a Master’s in Bio-mechanics has done me right. I was out when the higher-ups were interviewing you, but I’m sure we can trust management’s judgement. Follow me.”

Phelps started to lead Congden down the hallway. Bartlett took a few steps with them until a cool cross-glance from Phelps let him know his role had ended.

Congden looked over her shoulder to see him walking away, cell phone low at his side as if momentarily forgotten. “Thanks for the intro tour, Vincent!”

He raised an arm and pivoted with a grateful smile. “It’s Vince but close enough! Good luck!”

Phelps led Congden past lab after lab after lab. Finally Phelps indicated a small placard on the wall.

BRAIN POD

“Your new home away from home,” Phelps said. He indicated the small camera in the wall while tapping a small keyboard with his other hand. “No badge stuff here. Let’s get a retinal imprint of you.”

She stared as a yellow light alongside the camera went green. With a metallic click the pod door unlocked and swung inward.

“After you,” he said.

Congden crossed the threshold. Phelps stepped behind her and pulled up short as a glass pane slid before him, accompanied by an unnerving tone and stern computer voice.

“Failure to scan for entry. Please scan now. Failure to scan for entry. Please scan now. You have ten seconds to comply before the security team is alerted.”

Congden spun, her mouth and eyes wide. “Oh damn -- did I do that?”

Phelps rapped on the glass between them, shook his head as he backed up. “Nah, I did. Just demonstrating what happens when you don’t follow entrance protocol.”

Phelps stared into the retina reader. The glass barrier slid into the wall and he approached Congden and led her down the hall. “Cool, you’re in. Now you can access any of the labs.”

“I’ll try not to follow anyone in too closely,” Congden said. “Do all the doors have that scary security protocol?”

Phelps gave a half-smile. “Even the Surgery Center.”

“I thought hospitals handle the surgery.”

“For the clients, yeah. Ours is for the quality assurance and research. Cadaver stuff for the most part, sometimes pigs. Nerve tissue connections, ligament and tendon connections, that kind of thing.”

They moved through a maze of labs with glass walls revealing the people and equipment within. They halted at Lab B31. The glass walls here were dark and visually impenetrable, having been coated with tinting.

“This one’s different,” Congden said.

“Our primary researcher is world renowned Dr. Bender,” Phelps said. “And he doesn’t want his support crew getting distracted by the fish bowl effect.”

Inside, overhead lights basked in harsh white a dozen rows of high counter tops and hard tiled flooring. The glare made Congden squint a little. Squarish specimen containers with rubber membrane attachments for arm holes -- known by the highly scientific name of glove boxes -- dominated the counters, with several computer stations positioned among them. Plastic tubing ran above, into and below the glove boxes.

“This is where we do the brain washing,” Phelps said.

Congden snorted.

“It’s a pun but also true,” Phelps said. “Observe.”

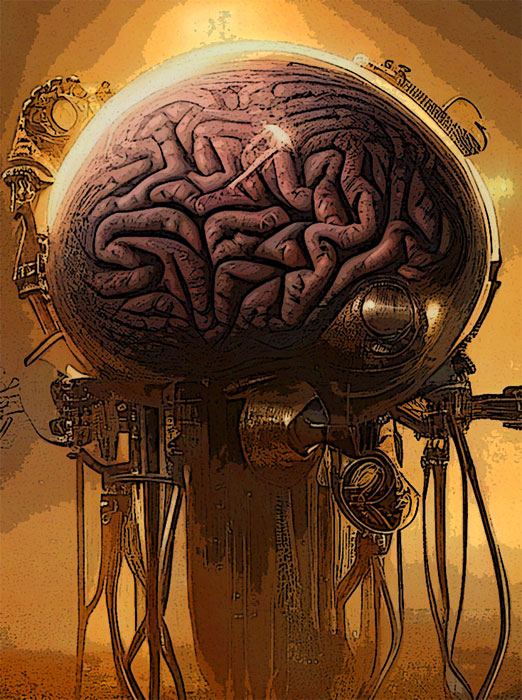

At a glove box labeled DB-1382, he reached inside via the rubber membranes. As Congden leaned to peer through the glass, Phelps grasped the melon-sized bowl and raised the lid. Inside was a mass of tiny spheres and crisscrossing threads. Burgeoning nodes pushed beyond the central mass.

Congden’s brows raised. “So this is a collection of brain cells. AKA brain organoid.”

“And more. We start with human stem cells suspended in protein serum. The cells grow brain neurons that layer in and around tiny spheres. We bathe the stem cells with serum, and the neurons generate exponentially until they form brain organoids.”

Phelps reached for a side compartment of the glove box. In it was a needless syringe and a container tube of clear fluid. He mated the tube and syringe stub and pulled back thirty cubic centimeters.

He worked the syringe back and forth over the organoid while pushing the plunger. “Dish Brain-1382 here is our heavy hitter at nearly seven hundred million neurons.”

“Seven hundred mil -- isn’t that too many?” Congden said. “Vince was telling me about limits on brain growth. Ethical stuff and so on.”

“Bartlett isn’t a research scientist or a lab tech.”

The air seemed to tighten around them.

“There are eighty-six billion neurons on average in the human brain -- we’re nowhere near that. We’d like to see what a billion brings, then we’ll level off. We’ve made implants starting at a hundred million and progressively higher with no adverse effects.” He returned the fluid tube and syringe to the glove box drawer.

“This one’s in a bowl, not a dish,” Congden observed.

Phelps took an electronic wand now and held it over the organoid, then nodded at the metrics dashboard displayed on the nearby computer monitor. “Yeah, technically it’s a bowl brain now, but we stick to the original for historical tracking.”

On a side panel a light flickered. He clicked there and a grid appeared, superimposed over a real time image of the brain organoid and its neuron networks. Tiny lights flashed on the grid.

“Pretty,” Congden said.

“Impulses from our subject,” Phelps said. “It’s well beyond a basic brain organoid now. More than a collection of neurons, it’s got astrocytes and oligodendrocytes and is trending toward the realm of a human brain ... shrunken down to embryo size.”

“What -- it’s thinking?”

“Just saying hello. Its primitive occipital orbs – see the rounded spots there – are picking up a change in the room, maybe even motion. Maybe more -- hell, I wouldn’t be surprised.”

Congden watched the pinpoints of random lights twinkle on the grid superimposed over DB’s image. “It’s like it hears us.”

“It does, on a basic electric impulse level,” Phelps said, taking a laser pointer from his lab coat pocket and flashing the beam on a small squarish form encased in neurons. “The neurons have enveloped the electrode nanofiber scaffolding that has a micro WIFI connection and a tiny battery. DB provides the electric impulses to both send and receive data. Kind of like having an electronic ear.”

Congden’s eyes widened. “Incredible -- hello there DB!” She smiled and laughed, gazing down in the bowl.

The grid lights on the computer monitor flashed with more vigor, almost merrily.

Phelps stared down at the organoid. “This one is really spinning up neurons at hyper speed now. It was layering those neurons so fast we had to suspend it in a globe container.”

The smile faded from Congden’s face. “So DB-1382 here can see and hear and respond to external stimuli.”

“Your point?”

“It’s got to be conscious.” The sparkling grid reflected in Congden’s brown eyes.

Phelps shrugged. “Maybe it is -- who cares? It’s not human. It doesn’t have a body, just the primitive formations of a brain. What happens if it is self-aware? Rats are self-aware, and we use them.”

Congden was about to speak, hesitated, then succumbed to the urge. “But rats don’t come from human cells.”

“Humans are just another animal, Congden.”

“But a highly evolved one.”

Phelps shrugged. “In a lot of ways, yeah. But you have to ask, why would highly evolved animals destroy themselves? Maybe that’s the hallmark of an evolved species. We lost half the world’s population in this latest world war -- half!”

Phelps tapped the plastic brain bowl with DB-1382 floating inside, as if trying to get the attention of a fish in an aquarium. “Cities are still rebuilding, only now it’s taking longer because we have a smaller workforce and manufacturing is crawling to get productive again. We need new machinery to rebuild. Some parts of the cities will likely remain rubble for a century. Maybe they’ll never be completely rebuilt. Same with our population.”

Congden blinked as tears welled in her eyes. “My parents were killed. I was a casualty ... for a while. Concussions were bad. I know all about war.”

“We all do. So are we going to have an issue?” Phelps’ face tightened. “‘Cause if this work isn’t to your liking, maybe we should part ways.”

Fear stabbed at Congden’s stomach. She shook her head. Universities had only started accepting students again, and it cost money to support herself and pay tuition. Waiting tables wouldn’t do much to pad her resume. “No, no. All good here.”

His eyes remained hard. “Let’s get to work then.”

In the days that followed, Alicia Congden doused the brain organoids with protein serum and counted the brain neurons with the electronic wand over both petri dish and bowl specimens. Phelps normally checked on her, made sure she was performing her duties or had questions and then disappeared. In fact, she was seeing him less and less lately and she found herself alone with a lab full of growing organoids.

No one really came by the brain lab during her shifts, other than Phelps. He sometimes was accompanied one of the white coat scientists, a Dr. Gordon Bender, who rarely did more than just stare at her. Phelps introduced him as “the pre-eminent neuroscientist in the world.”

It was a little intimidating to go to the cafeteria not knowing anyone, so she most often just stayed in the lab. The coffee maker near one of the desks was her main source of energy on the busiest days.

Congden hummed and sang softly as she worked. The side panel on the computer monitor lit up like a container of fireflies. She reached into the glove box and removed the lid of DB-1382's bowl.

“Whoa.”

The bulging areas had formed into early stage brain lobes. Twin half-circles rose atop an early frontal lobe. In them were hints of darkness that slowly moved.

“Well, hello there, bright eyes!” Congden said, smiling down at DB-1382. “Those occipitals look like more than just early retinas to me. And wow, you are really taking shape.”

She moved from side to side, changing vantage points. The hints of darkness tracked her.

Ding! from the nearest computer display.

Congden looked. “Probably some text message from Phelps down in the surgery center.”

Hello World.

The sender’s profile name was 1382. The network of neurons superimposed over DB-1382 blinked like fireflies on the computer display nearest them.

“Uh, is this a joke from Phelps?”

But Phelps’ last message to her was yesterday. And while he could still create this account, he showed little inclination toward warmth or humor.

Another ding.

Not Phelps.

Her jaw dropped. She looked from the screen to DB-1382 and back again. “Oh my god. No way, no way, no wayyyy.”

Ding. Cong-den.

“Oh God! Look at you, reading and writing! Wait, this might not be good. You live in a bowl and were created from skin cells ... buuuuut since you’re here now, call me by my first name, Alicia.” She held up her company badge, tapping her first name with a finger nail. “See?”

Ding. Alicia.

The conversation flew back and forth. Congden lost track of time. When she finally noticed, the computer monitor displayed 9:11 pm.

“Oh hey, I’ve got to get going –”

The monitor abruptly winked out, then came on playing a television station. An old television show way back before World War III called Hee Haw. Country folk performing music and comical skits.

Congden smiled at the joke. “Hope you aren’t learning about the world just through that show.”

Another image change. Now a rocket ship lifted off from a private launch pad, with the American flag on the side. Commentators were excitedly describing the event.

Then more and more streaming channel changes occurred. Too fast for Congden to register more than a glimpse at a time.

“You can’t possibly ingest all that, can you?” she said. “No offense, but even though you keep growing, you’re a lot smaller than a fully developed brain.”

The monitor’s thousands of pinpoints glowed red, then a kaleidoscope of different colors.

Congden laughed. “Someone’s been doing more than playing pong.”

The screen went blank. The computer fell silent. A glow started, getting brighter and brighter to form a wavering image in the center of the screen. The image undulated and gradually coalesced into a series of thin, medium and bold lines.

A computer bar code.

It vanished, replaced by another image, almost like a license plate.

DB-1382.

The bar code and brain name switched places, faster and faster, until finally they blended together.

“Oh my god. You’re a genuine little bio-processor, aren’t you?”

A thumbs up emoji appeared, then dissolved. The monitor faded to black, then more images gradually appeared -- horrific images of World War III. Cities annihilated, people dead or wounded and forced to scatter to the suburbs and countryside.

Congden’s expression hardened. She started to reach for the mouse to take control, then lowered her arm. “Turn it off, DB.”

The monitor went dark, then gradually lit up again with images of a large indoor space white-washed by bright lights. Too large to classify as a room, it was more like an open-air arena. There were no fixed interior walls. Drone carts wheeled body parts to and from surgical bays patterned by strips of floor lights and mobile equipment, including surgery tables. Inside the partitions, humans and androids performed surgery on human cadavers and pigs, some to remove body parts, some to attach body parts.

“HRI’s surgical research center,” Congden said.

The image zoomed in on two men and an android around the head of a cadaver.

“Ha, there’s Phelps,” Congen said. “And our Dr. Bender. World-famous and creepy.”

Congden watched on DB-1382's monitor as Bender, wearing goggles with protruding lenses, removed a portion of the cadaver’s brain. He placed the excised portion in a specimen jar, suspended in preserving fluids, onto which Phelps screwed a cap and labeled and placed on a mobile tray. From another specimen jar Bender removed a brain organoid roughly the size of a ping pong ball. Thin strands of concentrated neurons hung from it as he held it just before the incision in the cadaver’s brain. Bender nodded to Phelps, now holding a computer tablet. The surgical android rolled close and halted beside the table.

One of the drone arms extended toward the incision point of the cadaver, then turned its metal hand upside down and flattened it, leaving the very end of its digits turned upward as a barrier.

Dr. Bender placed the brain organoid on the robotic hand. He carefully pulled fine strands of clustered neurons out.

Phelps slowly traced a finger on his tablet, moving the robotic hand closer and closer to the incision point of the cadaver’s head. The drone arm held the organoid tirelessly in place as the scientist opened a tray and removed a helix-shaped object. It had gaps and a series of fine connector endpoints.

“That’s got to be his Neural Interface Scaffolding,” Congden whispered.

Bender inserted the helix in the cadaver’s brain and connected tendrils to it, dousing with fluid as he operated. Finally he lifted the organoid body, connected its neurons to the scaffolding and stitched it in place as part of the cadaver’s brain. At the end he pressed a skull fragment over the opening. The android assistant moved aside.

Bender stepped back, rested his goggles on top of his head and removed his gloves while conversing with Phelps. Both stood in front of the cadaver. Phelps worked his computer tablet.

The cadaver’s eyes opened to gaze from the netherworld. Its hand raised, then an entire arm.

The men grinned and nodded at one another. They looked around as if conspiring, then turned back at their experiment. The cadaver’s eyes focused on nothing, but moved side to side, up and down. The arm mimicked the movement.

Congden gasped. “Holy crap -- better turn it off, DB. We don’t want to get in trouble!”

As the monitor image faded, the door of the brain lab opened. A drone cart wheeled in. Affixed to its center was a column of vertical scaffolding with a biological arm attached by the shoulder.

“What! No way.” Congden strode to the drone and looked it over. The arm waved. She moved back to the brain bowl.

With the monitor flashing a series of lights on the grid superimposed over the image of DB-1382, the drone went to the coffee machine and poured a cup, then wheeled it over and offered it to Congden.

Congden took the cup and had a sip. “Amazing! It’s cold, but still amazing. Be careful, DB. Show off too much and they might pull your plug or something.”

With a farewell wave the arm and drone departed. Congden and DB texted back and forth and time melted away.

Well after midnight, Phelps and Dr. Bender stumbled into the lab, laughing and cutting up with one another.

“Hey Congden, you’re still here!” Phelps said too loudly while strutting for the refrigerator.

Congden’s eyes shot wide. She closed the computer window chat with DB-1382 and stood. “Yeah! Was just leaving.”

“Why don’t we show her what we’ve been working on, Phelps?” Dr. Bender said, with a leering smile. He took a bottle from his lab coat pocket and took a gulp of Tennessee Whiskey, spilling some on the floor as he held it out toward Congden.

“Have a sip, Lady Hotness.”

Phelps laughed as he jerked on the refrigerator handle and bent in front of it. He hunted down a couple beers from the back and raised one in Congden’s direction. “Or how about some suds?”

“Uh, no,” Congden said, holding a palm outward. “I have to go home. All of this is recorded on company security cameras, right?”

“Negative,” Dr. Bender said, laughing a bit as he stepped toward her. “We pause the cameras while working on brain surgery. What we do is highly, highly, highly confident-she-al!”

Phelps howled and took a few gulps of beer.

“Gotta go -- so late!” Congden stepped quickly forward, turning her upper body to slide by the approaching research scientist.

Bender stepped clumsily closer, his arm extended like a barrier at a toll booth. His hungry gaze moved from her face to her bosom and remained there, unabashedly staring now.

Congden none-too-gently shoved Bender’s arm aside. Bender laughed and shook the bottle as a means of enticement, and spilling more of it to splash on the floor just before Congden planted her foot.

She slipped, arms flailing. With a cry she tried to grasp the nearest counter top, but couldn’t hold on. Her head struck the edge with a dull thud, rose upward on a slight rebound, then plummeted and struck the hard tiled floor with a sickening crunch. She cried out at the first impact and fell silent at the second. Blood oozed from beneath her head.

“What was that?” Phelps said, starting from the break area. “Oh no, Congden!”

Bender took a sip from his bottle, then kneeled beside the unmoving young woman. “She’s out! It was an accident, I swear! She just ... she just slipped and fell.”

Phelps felt the side of her neck.

“Wake her up, fool!” Bender said. “Slap her out of it!”

Phelps’ eyes were wide. His jaw trembled. His gaze fell to the widening pool of blood. “She’s dead. God!”

“No,” Bender said. “No, no, no, NO!”

Unseen by the men was the computer monitor, and the network of neurons on the grid superimposed over DB-1382 that pulsed repeatedly in unison. Yellow warnings.

Phelps sat back on the floor, eyes dazed and sober, face slack. “Jesus.”

“Wait, wait, wait,” Bender said. “There are defibrillators in the hallways!”

Phelps raced out and returned with the small case.

Her body arched, breasts bare but for the defib paddles. Three times, four times, five. The smell of burnt flesh wafted up.

The men, breathing hard, were on all fours beside Alicia Congden’s body.

“It was an accident!” Bender said. “I just ... I just reached a little. I didn’t hit her or anything! She slipped!”

“Yeah, but she slipped on your puddle of booze. There’ll be an investigation, and we have the foreign dignitary visiting tomorrow.” Phelps sat back and rubbed his temples.

“Only old people die from a fall like this, damn it!” Bender said.

“Maybe, but she mentioned concussions from the bombings during the war,” Phelps said. “One too many ....”

Bender rose and paced back and forth, a sheen of sweat on his face. He rubbed his jaw while gazing at the lifeless form of the clinic technician. Suddenly he stopped at the glove box with DB-1382 inside the brain bowl.

“Maybe we can bring her back.”

Phelps frowned. “We just tried, man! She’s gone. Her heart has stopped. Her brain is now dead. Her body is dead, all of it!”

The monitor display of DB-1382's neuron network pulsed in red now.

Bender stopped, contemplated, then paced some more. He raised a hand in a loose fist, working it back and forth as if keeping time. “You’ve seen how close we’ve come in the surgery center with cadavers. This is a rare new death. She might just need a boost in the brain from a new source!”

“You’re serious?” Phelps said. “The defib didn’t work.”

Bender leaned forward, fists clenched. “Think about it, Phelps! Necrosis has yet to set in. She just needs a steady source of brain impulses to take over what she already had.”

“We can’t replace an entire brain!”

“Not yet, but we already augment existing brains.”

“Living brains, Doctor.”

“The organoid will be the driver!” Bender said, gesturing with an open hand to the brain bowl of DB-1382. “It’s neurons will interlace those of her existing brain, dead but still viable -- just like we did with the cadaver earlier today. Don’t you see it?”

“I’m sorry, no.”

“The difference is she is recently deceased. We put her on a cardiopulmonary bypass machine to keep oxygenated blood flowing, implant both the NIS and the brain organoid, then shock the heart! The electrical impulses will travel throughout her body and find the living organoid. It will map itself to her existing brain pathways and reinstate them! It’s akin to an extra processor and battery pack in an android.”

Phelps rose slowly. “I don’t know. It’s just so ... experimental.”

“Isn’t that why we’re here?” Bender opened the glove box and eyed the small brain inside the bowl. “This is our most advanced organoid.” He put the cover back on and lifted the bowl. “Bring the lab tech to the surgery center while I prep this.”

When dawn arrived outside the HRI building, Alicia Congden’s body arched with the shock of the defibrillator paddles. Bender and Phelps observed her EKG monitor, positioned beside the now empty brain bowl.

A green flat line with the bright yellow dot traversing it ran right to left. Steady, unwanted tone.

Two more shocks.

Flat line.

“It was a hell of a try,” Phelps said.

Bender, haggard and wild-eyed, seemed to shrink. The air hissed from his lungs. His shoulders slumped, his gaze drifted away. “This isn’t going to look good for me.”

“It was an accident,” Phelps said.

“This procedure was no accident. Failure, yeah. Accident, no.”

“You’re the top neurosurgeon in the world,” Phelps said. “Everybody knows how many lives you’ve helped save, particularly with the war injured. They wouldn’t do anything to you even if you did murder her.”

Phelps pulled a sheet over Alicia Congen’s body and turned out the lights in their partition, sending the entire pod into relative darkness. They walked out in silence.

The whisper of the air conditioning played a solo after they departed.

... until a beep sounded.

A spike showed on Congden’s EKG monitor. Another beep. Another spike. Then two beeps, then one, then three. The flat line on the monitor suddenly danced with random spikes.

In the glow of the EKG monitor, the sheet rose and fell as Congden’s body took a halting breath, and then another. Slowly she sat up, the sheet sliding off her naked chest.

The EKG beeped at a staggered pace, then eased into a steady rhythm.

Congden’s eyes opened.

A low moan issued forth.

DB-1382 could fit in the palm of Congden’s hand, but had enough life force to meld with the neurons of Alicia Congden’s dead brain. A new stream of life flowed -- not enough to resurrect Alicia Congden fully, but enough to mesh with a new brain and become a hybrid being.

DB-Congden.

Their eyes were half-lidded and flat. The light that had once been in them was now dim. Their head moved in quirky starts and stops. They worked their arms. They swung their legs over the side of the bed, put their hands down at the edge and was about to push off when they felt the cool steel of a scalpel.

They picked it up. Contemplated it. In a violent world one needed a weapon, even a small one.

They adjusted the shirt and stood, took small uncertain steps toward a mobile closet just outside this surgical space. They found a surgical cap and put it on, covering the wound and incision plates. Also useful was a clean lab coat, into which they pocketed the scalpel.

DB-Congden’s mind flooded with images of World War III. Impersonal news footage of bombing and battles led to horrors both witnessed and endured. Death, rape, and killing. She’d witnessed and endured it all.

More images rushed by.

The suffering of refugee camps. Working whatever jobs she could find. Finding books to read. Slowly unlocking her mind’s potential. Trying college again. Trying to appear upbeat in the face of so much tragedy. Trying to claw her way back into a society clawing its own way back, only to lose her life being pursued once again. This time not on a battlefield but in a laboratory.

A question from Phelps kept looping in their mind: Why would highly evolved animals destroy themselves?

DB-Congden had the answer: To begin again as a new species.

They took halting steps toward the exit. Their stride gradually lengthened and smoothed out. Phelps and Bender might be in the lab.

Inside the pocket, they ran a thumb up the blade and felt the sting as skin parted, and the warmth of the seeping blood. The DB-1382 side of them had never felt physical pain before, and found it exquisite.

They might as well start with the men responsible for Congden’s demise.

A bit of history known to both of them hovered in the foreground of their mind; the Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and how it had triggered World War I.

In a few hours Ambassador Lievhan from the Global Peoples Alliance will arrive. She will make a speech and begin a tour of the facility. News coverage of the event will be real-time and global.

At the employee entrance to the labs, DB-Congden will take a quick step and follow closely behind the ambassador -- without badging in. By the time security gets past the bulletproof glass partition that slides before them, the scalpel will open a red invitation to World War IV.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.