Part I

When they deplaned, the first thing Suzanne noticed was how the vast tumbling veldt mirrored the soaring, cumulous-strewn sky through which she had just flown. The landscape was alive with granite boulders toppled and crashed together. For a moment, everything was topsy-turvy. Which was which: earth or sky, cloud or stone?

She hurried to catch up. Kerry had them all marching toward passport control, her grey sweatpants riding just below the crease of her bum. Emmy was on her tail, clutching a pack of cigarettes. Michelle came next, her rimless glasses gleaming as she took in the griminess of the airport, the overfull trash containers, the peeling paint and burned-out light bulbs. Before landing, she had said that she would wait to use an actual toilet, but she walked right past the first ladies room they came to. Would wait for the hotel.

The three nurses queued in a line that was shorter than the one reserved for nationals. That's where Suzanne queued and waited ... and waited. Finally her turn came. The man across the counter lifted his right index finger to indicate that she should slide him her passport. The bridge of his nose was wide and shallow. His forehead was broad. His black skin was sequined with perspiration. Not a muscle in his face moved as he flipped through the pages.

"I see many countries visited, madam. What I do not see is an exit stamp from the Republic of Zimbabwe."

"I guess that's because I never left Zimbabwe."

"But how could you return if you never left?"

Suzanne tried to appeal to his sense of humor about the paradox he posed. "Now that's a very good question." But his eyes continued to rebuke her. "It's because my passport was issued in Washington. I never left the country with this passport."

He flipped to the front of her passport and looked at her photograph. There was Suzanne, twenty-some years younger, lots of brown hair, happy that she was going to get a Zimbabwean passport, which had taken her over a year to arrange -- the Suzanne who ought to be on this trip with these young women, not Suzanne at fifty-one.

"This is decades ago," he observed. He looked back and forth twice from her picture to her person. "Ah, yes, now I understand. You were born in a nonexistent city in a nonexistent country," he said, translating the information in the passport about her birth in what was then known as Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, into the point he wanted to make. Now he did see the humor in the situation. "Do we call you a nonexistent Zimbabwean, then?" He was half-taunting, half-educating her. "We don't see many like you. Are you returning to live, or to visit?"

"To visit. If I decide to stay, I'll get the necessary papers."

She had no idea what the necessary papers would be and wondered if her brusqueness insulted him. It was better when she tried to be funny. But then, with surprising civility, he stamped her passport and slipped it back to her, again with that single finger.

"Welcome home, madam. We rejoice that you have decided to return after so many years abroad."

They left the airport for the hotel in a battered Peugeot taxi with some of their luggage roped to the roof. The dusty roadside was fringed by vendors on blankets selling squash, cornmeal, avocados, peppers and peanuts. A billboard with a picture of the president greeted new arrivals. Kerry sat up front with the taxi driver. Michelle, Suzanne, and Emmy were squeezed in back. The driver's name was Robert. As soon as they were in the car, he began pitching Kerry to hire him for the length of their stay.

"I can be at your service the whole time, 24 hours a day!" he almost sang. "I will take you to Great Zimbabwe where the spirits still live. I will take you to Victoria Falls. With this reliable car I will take you anywhere you wish to go. Or do you plan to go to the Bvumba Mountains? I know the whole country, you see. I have visited the Bvumba Mountains many times. Very, very beautiful, madam. I am at your service. You can trust me to take excellent care of you." He spoke lightly, swiftly, and urgently. What reason could there be to refuse him?

Suzanne remembered Great Zimbabwe almost as if it were sliding into her. She could see the shadows mottling the Great Enclosure. She could feel her father lifting her by the waist and putting her on his shoulders so that they could explore the site faster because her mother insisted on staying in the car. She had already seen Stonehenge, she said, built long before this ... this what?

Kerry told Robert that they were not tourists; they were a public health team and wouldn't need a car and driver.

In the rearview mirror, Suzanne saw the expression on Robert's lank face flutter. "Public health! You are doctors?"

"No, we're nurses."

"Nurses! Oh, ladies, ladies ..." Robert choked on a spasm of emotion before crying out, "My wife is sick with cholera. Our daughter is already dead, and there is no help at the clinic. They took down their tent -- no more cholera here, they say. No more cholera? Oh, my family! Oh, my poor wife! I'm afraid she will die. Can you help me? What can I do?"

The three women in the back seat listened to Robert while staring at Kerry, each foreseeing her reaction -- Kerry wouldn't let this go, she'd shed her travel fatigue instantly, miraculously confirmed in her judgment that Zimbabwe was the perfect choice for them within an hour of their arrival. She asked Robert his wife's symptoms. He said she had the vomiting, the cramping, and the diarrhea. She asked who was with her. He said the neighbor woman, Sarah, had promised to look after her, but she, too, had just lost a sick child, and her husband was gone to South Africa.

"We are fugitives! We have lost our homes! We live in a filthy camp where they leave us to die!"

Kerry asked very softly, "Where is this camp, Robert?"

"Only twenty kilometers away, madam."

Without consulting the others, Kerry told Robert to take them to his wife.

Michelle groaned, "We've been traveling two solid days!" Emmy placed her hand on Michelle's thigh but Michelle still complained, "What can we possibly do?"

"We can use the Pedialyte we brought with us," Kerry said. "She needs to be rehydrated."

"If it's not too late," Emmy whispered to Suzanne.

Robert made a U-turn across the grassless median strip. The burgeoning conurbation that a moment ago vaulted directly ahead of them -- the slim chalk strokes of office towers and ziggurat arrays of apartment blocks -- tumbled out of view. When they turned off the highway onto a secondary road, the old Peugeot began recoiling spastically. They passed by crumbling walls smeared with gaudy political posters. They rocked beside fields that had, Suzanne realized, been scraped flat -- but not clean -- of shantytowns. This was what she'd read about, Operation Murambatsvina: drive out trash. Yet the trash remained. Strips of corrugated metal and fencing material were scattered everywhere, as were mottled mounds of cloth, cardboard, wiring and plastic pipe. Only the people were gone.

They passed through a grid of box-like dwellings -- not bungalows, not cottages: small cinderblock cubes. Children, old people, and idle men and women stared at them. None looked well. Suzanne last saw faces like these in her father's study. She heard his projector ticking. She remembered the window-like quality of the screen he never took down. His films were like something in which people had been entombed, lost, like the people they were passing. Looking up out of the grave.

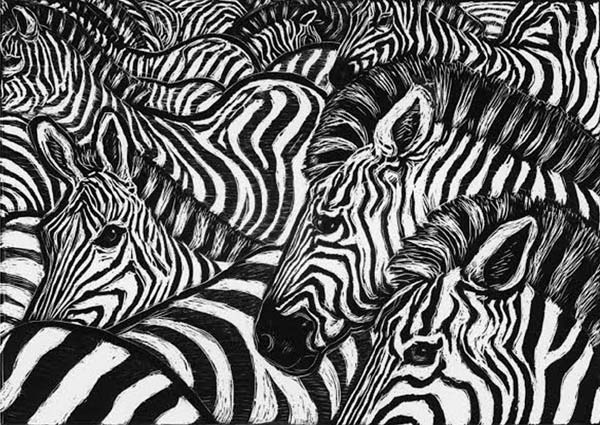

"Would you draw this?" Emmy asked.

Suzanne said she might. A man's skeletal hands. The slack cant of a woman's hips, her listless eyes. Human billboards, not posing, real: offering a warning, not a welcome. She listened to Kerry instruct Robert in the facts of cholera as if she were speaking to a college student. Why did she have to be so specific? Enterotoxins ... shock ... death in as little as three hours. She was saying these things to a man who must have left his wife sick with cholera more than three hours ago. Three hours ago they were in the plane. Three hours ago Suzanne was recounting to Michelle her conversation with her mother before they left. Her mother was perversely delighted that she couldn't recall if the street they had lived on in Salisbury was called Juniper or Jasmine or Jericho. "Why do you think that pleased her?" Michelle asked. Suzanne didn't want to say that her mother blamed Zimbabwe, née Southern Rhodesia, for wrecking her life by saddling her with children. "But who knows? I can't always tell what's going on with her." "Alzheimer's?" Michelle asked. "Not unless she's had it for the last fifty years," Suzanne said. Michelle liked this answer. "The whole world has Alzheimer's; that's why it scares us so much. Can she live by herself?" "She's glommed onto a man who dotes on her and behaves like a fourteen-year-old with him. He thinks that's marvelous." "Does she ever attack him?" "Oh, yes, she's wicked." "What does he do then?" "He gets a look on his face of utter confusion and begins slavishly apologizing. Then she tells him to shut up and it all blows over. Never happened."

Robert drove slowly across a barren field. "We let them see us coming," he said, referring to the soldiers sitting under an awning at the edge of a sprawling encampment -- tattered tarps and sheets of plastic stretched over low walls made of stacked barrels and gathered stones and truck tires and piles of brush.

"We have to pass through armed guards?" Emmy asked.

"It will not be a problem. I have arrangements," Robert said.

"You bribe them?" Kerry asked.

"I buy my petrol from them," Robert said.

Michelle said, "If I don't find a clean toilet, I'm going to turn into concrete from the inside out."

Kerry looked at Michelle reprovingly. "Remember why we're here, please."

"Yes, ma'am," Emmy said.

Suzanne's eyes wandered along the sagging barbed wire fencing in which the encampment was enclosed. What if there was no sick wife? Who would know what happened to them? The sentry's smile flashed brilliantly as he waved Robert through. Now they were twisting into a kind of pastry of trash, iced with reddish brown dust, ubiquitous and inescapable. She got out her camera and began taking pictures. She felt Emmy staring at her.

"Well, I wasn't serious," Emmy said.

"About what?" Suzanne asked.

"About you drawing this."

Kerry twisted around again, "Emmy, it's why she's here."

"Oh, I know, I know, but -- "

"Are you going to be able to explain this when we get back?"

"Are we ever going to get back?" Michelle asked.

The Peugeot creaked to a halt in front of an actual structure, its entrance shielded by a privacy wall. "With my car I was able to bring us cinderblocks," Robert said, "but no mortar. It is like everything in Zimbabwe; nothing holds it together."

Thin, ragged children surrounded the car. Kerry already had everything planned: the nurses would go inside while Suzanne remained outside guarding the luggage. "They're really sweet," Kerry said, referring to the children, "but they'll steal us blind. I saw it over and over again in Rwanda. Don't let them touch anything," she instructed Suzanne.

The children asked Suzanne her name and where she came from. She couldn't say Zimbabwe, not to them. It made no sense. So she said America.

"America!" a boy cried out.

A little girl rubbed her head against Suzanne's thigh. Her hair was lice-ridden. Suzanne forced herself to rest a hand on her bony shoulder and study the writhing insects. Then she realized, when the girl wrapped her arm around her thigh, that she was being distracted. Two boys were on the roof of the car, about to make off with a suitcase.

"Hey, stop that!"

The boys began fiddling faster to slip the suitcase out from under the ropes Robert had used to keep things in place.

"Kerry! Robert!" Suzanne called, trying to pull herself away from the little girl.

Kerry ran out, a stethoscope around her neck. "What is it?"

"They're going to take that suitcase!"

"Well, don't let them! The woman's dying in there, Suzanne. I can't do my job and your job, too." But Kerry reached up and grabbed one of the two boys by the belt and pulled him down to the ground, where she pushed him at Suzanne, presumably so that Suzanne would administer some kind of justice. Meanwhile the other boy had his hands on a backpack and began running away with it.

"That's Emmy's!" Kerry shouted. "Emmy!" she called into Robert's house, "one of these kids has your backpack!"

Suzanne realized that she now had two children restraining her -- the girl and the boy. Kerry could see this, too, so she began running after the thief. Before she could catch him, he dropped the backpack and disappeared behind something or into something or under something -- impossible to tell -- just disappeared, vanished. Kerry returned with the backpack and began shooing the children away from the car. The children made this into a game, fleeing from Kerry toward Suzanne, who was doing the same thing on the other side of the car, and then fleeing back toward Kerry, taunting her and trying to pull on the straps of the backpack to make her lose her balance.

At last a gaunt woman strode out of Robert's house, hissing at the children and clapping her hands. Her eye sockets were deep and weary. Her earlobes were half as long as her ears. "The cholera! The cholera!" the woman admonished. "It will kill you bad ones! Kill you all!"

The children fled her, shrieking with fearful glee.

In the house, Robert began wailing. Kerry and the gaunt woman hurried to join Michelle and Emmy in comforting him.

* * *

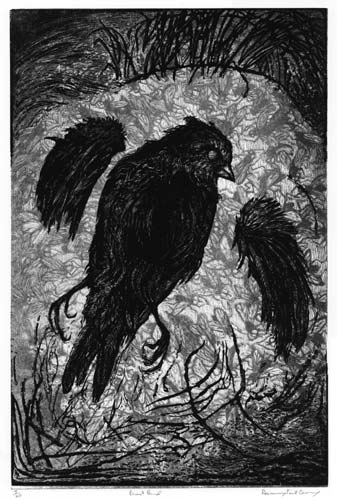

With more than sixty stories and three novellas in print and online literary journals, Robert Earle is one of the more widely published short fiction writers in America. He also has published two novels and two books of nonfiction. "In the Land of Zim" was inspired in part by two women committed to Africa and its peoples -- Jocelyn Kelly, Director of the Harvard Women in War Program for the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, and Rosemary Feit Covey, internationally acclaimed artist, born in Johannesburg, South Africa.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.