Part VI

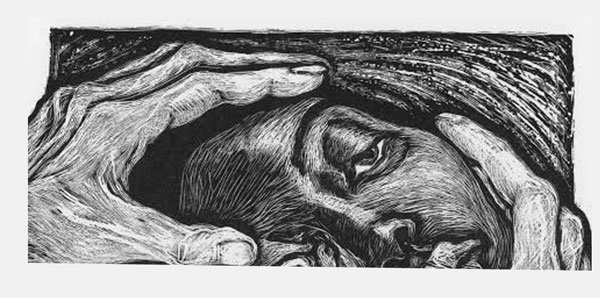

Three days of running the clinic felt like a lifetime to Suzanne. The things that normally transpired in her seemed to have disappeared -- the need to pass hours alone, sketching and doing research and daydreaming; the obsession with evoking intrigue from lines in conflict, little skirmishes in the corner of an eye or a span of lips; the frustrations and excitement of making prints, rolling the ink and studying its infinite glistening wetness and sheen. She was agitated but alert and unaccountably pleased. What was this mix of sharp, prickling, stimulating emotions? In coming to Zimbabwe could she really have stumbled across the threshold of the Land of Zim, the fable she had invented to console and entertain herself when her art seemed to be going nowhere no matter how hard she tried? Maybe by not working, but by not working here, in this particular place, she was doing her best work, or preparing for her best work, even if each day was wearing and numbing, and just as the girls had said about nursing in general, overwhelming: an endless frieze of human drama, a Canterbury Tales, a Decameron, all of Dickens.

After they ate each evening, she organized her pile of paperwork -- the ministry forms and the group's treatment records and Emmy's research questionnaires. Then she uploaded any pictures she had taken onto their laptop. She didn't study these photos, or the sketches she'd made (only three or four a day.) Instead she listened to Kerry work the phone, placing calls to various people at ICFC. These were the mysterious gods who controlled their destiny. Quite methodically, Kerry would dial Richard, Geoff and Crystal in sequence; this seemed to be their rank order, Richard being the boss, Geoff the middleman, and Crystal the gofer, the only one they'd met when she came to the hotel the evening Suzanne had been with the Vuambas to drop off insulated sacks for cold drinks and blue ICFC baseball caps with a white caduceus embroidered on the crown. As she deemed necessary, Kerry would be coaxing, demanding, straightforward, conspiratorial, and stressed. She was an actress, Suzanne realized, a masterful shape-shifter. Her tones and inflections ricocheted around the hotel room as if thrown in all directions by a ventriloquist. She wanted ICFC to know how well they were doing; she wanted salt tablets and zinc tablets and paper bed sheets and disinfectant spray bottles that didn't clog. What about the field assignment? What did 'not long' mean? She needed guidance; she needed something to tell Michelle and Emmy and Suzanne (sitting right there, taking it all in.) No, they couldn't begin their research under these circumstances; this encampment's population was in too much flux; there might be two thousand people there; and they were all afraid, palpably afraid -- you could feel it in their lax skin, literally, and see it in their tiny pupils. These people needed a full-scale medical field station with at least two doctors and six nurses.

More than anything, Kerry entered empathetically into the thought process of the people with whom she spoke. She'd listen for long spells. She'd console. She'd offer to "think" with them while probing for information about the Ministry of Health and how politicized it had become ... and underfunded ... and poorly administered. Was Mrs. Kahiya likely to revisit their clinic? Kerry said she worried about that. She was afraid Emmy might say something Mrs. Kahiya wouldn't like. She hoped they could head that off and asked Richard to reassure the ministry that no more visits were necessary. She asked Geoff and Crystal the same thing. And she always ended her conversations by saying how glad she was that ICFC had things under control (Really? Suzanne wondered) and that she was certain they'd receive good news about being transferred out into the countryside soon -- making something so by wishing it were so and inspiring absurd confidence in Suzanne, who needed this boost at the end of the day when she was exhausted and didn't want to fall into worrying that Kerry's super-reality and omnicompetence (the others were amazing too) would not print well when it dried

Twice Suzanne was able to establish a Skype connection with Andy, but it depressed her that she could not seem to convey to him what Zimbabwe was "like," so fundamentally indescribable in the virtual Internet world where there was no hunger, no cholera, no heat, no rank smell of sweat and diarrhea and suppurating skin. He kept interrupting in ways that told her he didn't have any idea what she was experiencing. He said that he had been reading about the currency reform Zimbabwe would have to undergo. He said he'd Googled an epidemiological study that suggested the rainy season might make the cholera epidemic a lot worse. Suzanne let him talk, knowing he was just filling in the blanks of what for him was the real framework of these discussions, Suzanne's return to New Portshead. He wasn't letting her stay there for good, he joked. She did not disbelieve this. She did not believe it, either. Sometimes she thought that Zimbabwe already had infiltrated and expropriated her. Samuel and Amadika had taken her parents' place. Suzanne Vuamba had taken Suzanne's place. Tatenda had taken her sister Allie's place. Squash and beans had crowded out the grass and flowers. The dog had chased away the monkeys. This was an upside down world ... this was an inside out world ... Suzanne would need time to assimilate it. So far she was doing all the right things to help the nurses, but telling Andy that missed the point. She felt as though her childhood epidermis had been torn away when her family left for America when she was eight and now it was being torn away again and many sharp new things were being embedded in her flesh. Another facet of the Land of Zim: its bite.

On the fourth day Emmy insisted on leaving the tent to try to map the camp and come up with some kind of census and see where the cholera had its sources. Kerry objected that this wasn't their research site. Emmy said the way things were going it might end up being their research site; she didn't want to go back to Connecticut without any idea of where they had been. She asked Suzanne to come along, and Suzanne agreed. Kerry saw there was no use arguing, but she said they would have to be accompanied, so Robert went, too.

At the outset, there appeared to be no rhyme or reason to the encampment. People dwelled in whatever sheltered them: beneath plastic sheets; behind pieces of cardboard; under a tree whose limbs were covered with cloth that shielded them from the sun, if not the wind; in wooden shipping containers; beneath an overturned trailer propped up on rocks. People defecated and urinated all over the place. Children were the worst, shamelessly pooping wherever the need struck, or tinkling into ragged rivulets that fed into shallow pools used for drinking and cooking water.

Emmy made her map by recording the number of people living in a given spot. Suzanne took photos as they made their way around, and all the time Robert talked, filling the air with a broken, mournful elegy, the chorus of which was a phrase he repeated at least a dozen times, "... so many bad things ... so many bad, bad things ..." and the verses of which were variants on the themes of children without mothers and mothers without food and fathers without work. "I go into Harare, and I come here," he would say, making it a statement. Then he would say, "I go into Harare and I come here?" making it into a question. He had been a man, but now he was a nothing, a nothing like that listless fellow sitting on a box, a nothing like another man spooning his bowl clean of mealie meal while a hungry child watched him, "... so many bad things ... so many bad, bad things ..."

Emmy's map twisted with the land, following a low ridge, rounding it and opening out into a sweep of bare earth bordered by ragged grassy bush. She insisted Robert talk to people who didn't want to talk to him because she wanted to document her suspicion about exactly why they were so sullen and mute. She was right: No one knew anyone else. They weren't kin. They hadn't been bulldozed out of the same shantytowns. They hadn't come to Harare from the same parts of Zimbabwe in the first place.

Almost no adult or adolescent walked anywhere without carrying something -- cans, bottles, pieces of wood, boxes, bags. They wore generic manufactured clothing. Only the men were still and silent when they sat; the women were always busy mending things or picking at their children's hair.

Suzanne admired Emmy's technique of zigzagging as she walked, angling from one edge of the encampment to the other while keeping count of her paces. She said she'd been taught this technique in a demography class and never had a chance to employ it. It sort of worked, but there was a lot of guessing built into the result because they couldn't follow straight lines even when they added what Emmy called "sub-zigs and sub-zags."

It took them two hours to reach the fringe of the grassland where Emmy announced her conclusions. There were more or less eleven hundred people in the encampment, which had started because the ridge sheltered it somewhat from the wind but largely occupied a broad open wash that would saturate during the rainy season.

"The grasses surrounding it will function as a kind of sponge during the rainy season until they're soaked. Then they'll release, and since the wash bed will already be sopped, the water will slide everywhere like a kind of river delta and drive people closer together. That's when the cholera will really spike. I don't know why the government doesn't see that and move them out."

They had climbed a few paces up into the bordering bush and were looking south at the tattered encampment, sliced through by the scrubby ridge. The sky, so pure when they had arrived, had grown hazy; the air felt sulky and mean-spirited.

Suzanne said, "Maybe the government is doing exactly what it wants."

"So many bad, bad things," Robert said.

A doctor from the ministry visited them. He arrived alone in a white pickup truck, a tall handsome man with straight eyebrows and a vast dome of a head. "I heard someone was doing something out here. Would you mind if I looked around?"

There were two cholera victims in the back room. He kneeled to examine their eyes, mouths, throat glands, heart function and respiration.

"Well, now ..." he said to himself, apparently contemplating not just their condition but also the fact that they were here in this first aid tent. "So you rehydrate them?" he asked, not waiting for a reply. "That's good. You're saving lives."

Suzanne saw, and also felt, the effect these words had on Kerry, Michelle and Emmy. Their eyes glowed; they smiled at each other; it was as though they were the ones who had been rehydrated.

"But I gather you will not be here long," the doctor continued. "Mrs. Kahiya has categorized this clinic as temporary."

Kerry said they had met Mrs. Kahiya, and they already had been there longer than they expected.

"But you can see the need, can't you?" Emmy asked the doctor. "We think there are over a thousand people here."

The doctor pursed his lips. "Most definitely there's a need."

"Until we stumbled out here, I'm not sure these people were on any map," Emmy complained.

The doctor was a man in his thirties, well fed, strong. Almost beautiful. The antithesis of the men in the encampment. Godly, not withered and wretched. "I beg your pardon," he said "but they were indeed on a map. There was a station outside the fence line until just two weeks ago. I was the physician assigned to it."

He seemed to think he'd put the issue to rest, but Emmy persisted. "Then you should know the situation here better than anyone. Weren't you busy?"

"I am busy wherever I work in Zimbabwe," he answered sharply. "We are a poor country. We have too few doctors and too many sick people, as you have seen."

Trying to soothe things, Kerry said, "Of course. We understand." She then asked him if he would suggest to ICFC that they give them antiretroviral drugs for HIV positive patients. "Four women have asked us if that would be possible. One was pregnant. We saw at least two others who had all the early symptoms." Her tone had been as collegial and friendly as she could make it, but the doctor regarded her request as out of line.

"No, no, no, antiretroviral therapy must be consistent and stable, and you will not be here long. Your patients' treatment would be interrupted. No continuity of care -- this is bad." To underscore his point, he walked outside and approached an emaciated man who wore a wet cloth under his hat. "Have you been diagnosed as HIV positive, sir?" The man denied it. The doctor ignored this denial as he pulled on some surgical gloves. "Let me see your mouth." The doctor took a pen-sized flashlight out of his breast pocket and peered into the man's mouth. "Such lesions. They must be uncomfortable." He then palpated the glands on his throat and under his arms and inspected a bruise on his right wrist. "Sir, you need a blood test. These nurses cannot help you. They have no laboratory facilities. Go into Harare where you can be properly assessed."

As the man shuffled away, some others in line joined him, evidently not wanting to hear a similar verdict. The doctor pulled off his gloves and handed them to Kerry for disposal.

"Now, ladies," he said severely, "I want you to listen to me. If you let these people bring you every ache and pain on top of ailments far beyond your capacity, you will end up doing no one any good. Do not mislead, do not promise, do not predict. And I want you to stop everything you are doing right now and disinfect your tent. It's filthy. You must clean it."

Before getting into his truck, he instructed those people remaining in line to return the next day when the facility was sanitary enough to accept them.

Kerry's response to this encounter was to urge everyone to focus on what they could do, not what they couldn't do, just as the ministry doctor said. "We've got to play along."

Emmy's response was that they should tell ICFC that they wouldn't work in the camp anymore because these conditions were impossible. "I say we sit in the hotel until we get the assignment they promised."

Michelle said no, they should just keep doing what they were doing, but do it more slowly. "We've got to back off, or we're going to get sick ourselves."

Kerry said she agreed with Michelle, but she then insisted they wipe down the tent as fast as they could so that they could reopen the clinic that afternoon.

"Kerry, Kerry, Kerry," Emmy said in disbelief, "didn't you hear what Michelle just said?"

Kerry again had her way, coaxing, dominating, and directing everyone. All four of them began spraying and wiping and organizing their medicines and supplies so they could update the inventory. Suzanne welcomed all this activity because she had been designated as the maintenance manager; and if that was so, she was the one who had failed more spectacularly than anyone else. The tent's walls were difficult to clean because they billowed away from the touch; the floor was filthy; they had almost no gauze left and several instruments were missing: scissors, forceps, hemostats, and a stethoscope. Also a bedpan -- gone. Who would take a bedpan?

"Maybe the same person who took two catheter bags," Michelle said.

The tent seemed to fill not just with the acrid scent of antiseptic, but an odor of anxiety and a sense of how precarious and exposed their operation really was. Michelle went around with a roll of adhesive tape to seal tears in the tent. Emmy commented that when the rains came and the encampment flooded, the tent's roof would leak like a sieve. Two hours of hard work resolved some of their disquiet. Suzanne attributed this partly to the way the conversation drifted to fantasizing about where they'd end up next. It seemed strange to hear them talking about departing just when they were gearing up again and when they all knew the work in the encampment would be endless -- they'd never treat all the sick people here -- but that was what they seemed to be fleeing, perhaps exactly the crisis Suzanne felt had to happen and most wanted to experience. Kerry said she thought they'd be near the mines -- and maybe in a tent complex there, too. Michelle had a picture of them using a town hall somewhere in the bush. Emmy had dreamed of being in the east, in the mountains, and thought maybe the population would be mixed, white farmers as well as black farmers, and lots of water, too much water, and mosquitoes and rashes and funguses and pulmonary issues, but at least the water would be running and fresh. She hadn't thought they would ever really see cholera, or that if they did, they could deal with it as effectively as they had.

"So far so good," Kerry said. "Except for Robert's wife, we've had six cases in four days and six apparent recoveries, including one child."

They were almost cheery as they began scrubbing their hands and told Sarah, who had stood waiting outside the tent flap, to put out word that they would reopen in a few minutes.

"Now we'll do what you say and take it slow," Kerry told Michelle. "And every day we'll repeat what we just did: clean this place."

"It looks good," Emmy conceded. "We can't expect Suzanne to keep everything in order by herself."

"No," Kerry said. "We'll just always stop one hour early and do what's necessary. Not let things get out of hand like your studio," she said to Suzanne. "That's always a mess."

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.