Part IV

Suzanne walked out to the old Peugeot taxi with Robert and Sarah. She had an idea that she had had ever since Kerry first made her proposal; it was frightening but wouldn't go away. And now she felt a powerful urge to plunge ahead, fueled by the possibility that tomorrow, or the next day, she would find herself in Robert's encampment again, being swallowed by it, being digested by its sewage and disease. This was the moment; there wouldn't be any better.

"Robert, I wanted to ask you something."

"I am at your service, madam."

"Have you ever heard of a street called Juniper or Joshua or Jasmine?"

"No, but there are many streets in Harare. Even a taxi driver does not know them all."

"How about one with a name that simply sounds like that? One that begins with J?"

Sarah said, "There is Jasper Street."

"Yes, Jasper Street," Robert agreed.

Suzanne remembered that the monkey she'd put in her little pink suitcase was carved out of red jasper. (What had happened to that monkey?) "Is it far?"

"Not close, but not far."

"Would you take me there?"

"Right now, madam?"

"Yes, right now. I don't know the exact address. I just think it might be where I was born, a house on Jasper Street. I'll recognize it."

Sarah and Robert exchanged a glance that they would never have exchanged in Suzanne's presence when she was a child, nothing more than a flicker of doubt or perhaps condescension, but Suzanne might only be imagining this. How well could she say she knew the people of Zimbabwe? She had one true black friend, Amadika, the daughter of Margaret the cook and Reynolds the houseboy. Except for Amadika, what Suzanne remembered were moats of silence separating blacks from whites, averted eyes, self-willed invisibility, and inscrutability. Her mother often scolded Reynolds for being lazy. Reynolds, she recalled, freely admitted it, as did Margaret. "He feel so sorry for himself, ma'am. I do not know why I married him." It always calmed her mother to hear Margaret deprecate Reynolds, who dolefully nodded his head, agreeing that he deserved whatever criticism he received.

They got into the taxi, Suzanne in the back seat, and drove across Harare, a city of magnificent space (infinitely more handsome than New Portshead, Connecticut) into a neighborhood some miles from the center of town that was verdant and flowery and yet somehow cobwebbed with the gray strands of time: out of date, humble, old-fashioned.

Did she remember this? Yes, some of it. She remembered the fragrances. She remembered the lassitude. She remembered the vegetal abundance. And she remembered her parents not talking -- as Robert and Sarah were not talking. Or, if one of them talked, it was her mother who talked while her father drove exactly as Robert drove, European-style, not slouching, exercising great care and deliberation.

They were some distance within this particular neighborhood when Robert slowed to make a left turn and she saw the sign. Jasper Street appeared to be where the city began to peter out. The simplicity and quietude of a neighborhood like this -- it might be the neighborhood -- would be what drove her mother batty; she liked to be in the center of things. But the seclusion would be what permitted her father do what he wanted to do without distraction, and life here had the quality of how Suzanne saw things, too, their underside and solitude. Images, partial and whole, tumbled through her mind: The garden. The monkeys melting her with their lambent brown eyes. The veranda exactly as she later engraved it. Rain clattering on the metal roof. Her hands on the windowsill in her room as she looked out into the gray shimmering veil flooding the lawns and gushing down the drain spouts.

"Please slow down a little bit."

Robert slowed to a crawl. Suzanne studied what she could see of each house through the gates and fences and beyond the walls as they edged past. She gasped when she saw the dormers. Robert understood. He stopped. The jacaranda in the front lawn, the flowerbed along the driveway, the honey-thick spray of bountiful, riotous color outwitting time and prying open the past. But also: the scabbiness of the exterior plaster, the rusty Land Rover, the hoary concrete walkway to the battered front steps. So run-down. So defeated.

"Do you want me to announce you?" Robert asked.

"Announce me?" She couldn't. She thought again, but no, she had just wanted to ...

A black man in a white shirt and black trousers came to the front door. He waved the back of his hand to shoo them along.

"Madam?" Robert asked.

Suzanne stepped out onto the gravel. She wasn't dressed to call on someone -- wearing her floppy sunhat, her jersey top, her khaki shorts and sandals -- but the man stepped out onto the porch and waited for her at the top of the steps.

"May I help you?"

"I just wanted to apologize for disturbing you. I was born in this house. I haven't seen it in almost fifty years."

He was a gaunt man with a large nose and deep wrinkles cascading beneath his eyes. His shirt was very white and starchy, but he was not starchy. Her sudden appearance on his front lawn seemed to interest him. "You left the country?"

"My parents left when I was eight." Suzanne shrugged her shoulders, feigning helpless youth. There had always been a little Charlie Chaplin in her. "What could I do? I had to go with them."

The man smiled sympathetically at her childish plight. "Do you mean to say they built this house?"

"No, I don't think so. Someone else did." Suzanne apologized for not introducing herself immediately and did so now. The man reciprocated -- Samuel Vuamba, certified public accountant. "May I walk around to look into the garden?" she asked. "I used to play there with my friend, Amadika."

Samuel Vuamba pursed his lips and cast a glance at Robert and Sarah out in the taxi. "Your friend Amadika?" He told Suzanne that she was welcome to walk around to the garden. "Don't worry about the dog. He's only there to keep the monkeys away. We don't want them eating our vegetables. Excuse me while I tell my wife you are here."

She maintained a casual walking pace until she heard the door close behind Samuel Vuamba and then began to hurry. The garden was no longer a grassy lawn fringed by lush flowerbeds and gorgeous blooming trees. It was a vegetable garden, planted with tomatoes, peppers, corn, eggplants, and melons all the way to the walls, which were topped with coils of barbed wire. But the plants and vines were shriveled this late in the dry season, almost picked clean. The veranda was cluttered with garden tools, watering cans, pots, burlap bags, and boxes of potatoes. The monkey-chasing dog, a mottled mongrel of some kind, looked inquisitively at her from where it rested beneath a rocking chair.

"Suzanne?"

Suzanne turned to look at an immense black woman in a green dress with large golden hoop earrings and a look on her face of utter stupefaction.

"Yes?"

"I am Amadika, Suzanne! Amadika!"

Once, years ago, Suzanne received a strong shock from an electric grinder she used to sharpen her engraving tools. The shock was cold and heavy and ran right up her wrist to her elbow. She felt that kind of shock pass through her now as the woman who said she was Amadika, not much taller than Suzanne but twice as wide, pulled her to her bosom. Samuel Vuamba stood behind them laughing. Amadika whirled Suzanne around. Her sunhat flew off. She saw two more black women, followed by a handful of children, come out of the house to stare at Amadika celebrating this reunion with her childhood friend.

"Come, come sit with us and tell us why you are here!" Amadika shrieked. "Meet my daughters and grandchildren -- it's been so long!"

After asking if Sarah and Robert might join them, Suzanne listened more than spoke during the next several hours. The Vuamba family brought extra chairs onto the veranda, but there weren't enough, forcing several grandchildren to sit on the floor. Eight of them lived in the house with their mothers and grandparents. Amadika's daughters, one named Suzanne (!), the other Tatenda, both were single mothers. Suzanne Vuamba was a short woman whose head was shaped somewhat like a radish; she trembled delicately as she stared at Suzanne. "I am your namesake, oh, how long I have wanted to meet you, my mother's Suzanne!" Her husband had died (no explanation how). Tatenda's husband had emigrated to South Africa, where he worked in Kimberly and sent the family remittances. She was almost as fat as her mother, wore a brilliant yellow bandana wrapped around her head and laughed richly as she watched Suzanne's gaze drift and float around the veranda, catching frequently on her namesake, an astounding African reincarnation before she had even died.

Amadika sat Suzanne next to her and held her hand and told her that after the Mosels left, she and her family stayed on in the sheds in the rear of the garden, awaiting the next occupant. They kept the house and grounds maintained, but no white family moved in. A year passed, then two. When Ian Smith declared Southern Rhodesia independent, more white families left Salisbury than arrived. Amadika's parents had no income, so they had expanded their gardening plot to feed the family. And at a given point in time, they decided that they would live in the back portion of the house, never letting themselves be seen from the street, and rent their sheds to another family, who arrived with a son about Amadika's age. This was Samuel Vuamba, Amadika said, affectionately nodding at her husband, "a boy far too clever for his own good." Samuel went all the way through high school and became an accountant by earning his degree at the University of Zimbabwe.

"But then he began helping Joshua Nkomo during the war!" Amadika cried, as if calling to Suzanne from a great distance. "He had a very good job during the day at a big trucking company, but was that good enough for him? No, no, no, Samuel Vuamba must help Joshua Nkomo manage his money! This made it very difficult for me to persuade my parents that I should marry him, you see. We were here, still, looking after this forgotten house, and Samuel's family lived with us, but at night, where was Samuel?"

"If you had welcomed me into your bed, would I have done these things?" Samuel joked.

"But you did get into my bed, Samuel Vuamba!" Amadika said.

"Not enough!" Samuel said, making everyone laugh. "Look at this -- only two children! Our girls have more children with no husbands at home than you had when I lived only a few feet away!"

Suzanne listened to Samuel and Amadika alternate in describing the war that led to Zimbabwe's independence as a time of terror and confusion. Samuel told her that her father, Fredrick Mosel, was regarded by many as a martyr to the truth, driven into exile because he insisted that there were at least two sides to Zimbabwe's story. Proof of this was the fact that the film archives he left at the university were destroyed.

"They wanted to deny us our history," Samuel said. "Let there be no record of who we were, and how we were treated, and how we survived."

She heard the story of Samuel's persecution when Robert Mugabe turned on Nkomo in the 1980s and his exile (separated from Amadika) in Zambia.

"This was when these girls," Samuel said, pointing to Suzanne and Tatenda, "developed all their bad habits."

Suzanne Vuamba smiled at her father; she was the color of cured tobacco. Tatenda Vuamba was darker, the color of black coffee. The children ranged in color and age, five girls, three boys, milk chocolate to molasses, the oldest perhaps fifteen. They were transfixed by what they were hearing and the presence of this small white woman with the lively brown eyes and pretty smile.

Samuel eventually returned to Zimbabwe and worked his way back into government, where stayed, but he was somber about the government's misguided policies. "I work in the Ministry of Finance, you see. I know we cannot print money forever. What we have is already worthless. We cannot afford to buy the paper we print it on."

Inside, the house was a disheveled version of the house Suzanne left when she was eight years old. The kitchen table, sink, and stove were the same. The floorboard moldings were missing or split. The sitting room furniture (also the same: the green easy chair, the blue sofa) was threadbare. Upstairs she entered the bedroom that had been hers. The butter yellow paint was almost faded white, and there were deep cracks in the walls. And no closet, she hadn't remembered that, just a battered armoire. Her parents' room, including the bed where Suzanne had been conceived, had long since been the bedroom of Samuel and Amadika, its extra floor space taken up by the sleeping pallets of several grandchildren.

Everything that had been her childhood had been transformed into the past, present and future of a family that felt more like her own than the one with which she traveled to America. Amadika's daughters and grandchildren followed her on this house tour like baby quails. Where she walked, they walked. When she stopped, they stopped. Amadika never let go of Suzanne's hand.

Downstairs again, Samuel cleared his throat and said gravely, "So now ... after all these years, the Mosels have returned to reclaim their property. Despite the ravages of time, I hope you find everything in order."

Suzanne looked at him in dismay. How could he suggest such a thing? But of course, think of what he and Amadika had just told her. Except for the house, life had never worked out for them as they might have wished. Samuel had been exiled; one of his sons-in-law was dead, the other was gone; and they had all these children to feed, wrapped in their mothers' arms, resting against their grandfather's shoulders, sprawled on burlap bags on the floor. Why not expect a white woman who said she'd always kept her citizenship to reclaim her family's abandoned house? Wouldn't that be the next blow?

"Oh, Samuel, no, I didn't come here to do any such thing."

"But it is your property," Amadika said.

Samuel said, "We have enjoyed usufruct but in no way enjoy ownership."

"What is usufruct?" Suzanne asked, regretting that her ignorance made her seem interested in exploring legalities. The entire clan, she realized, was staring at her in genuine fear

"Usufruct is the right to benefit from a property one does not own. I was able to establish that right, given your family's extended absence, but I did not dare pursue a declaration of abandonment so that I could acquire the deed."

"If we had, someone else might have outbid us," Amadika explained. She was perspiring heavily, releasing a mossy, musky smell. "Well, it's all long ago. Years ago. All we have ever paid are the taxes when your father stopped paying them. Since your father is dead, then your mother owns the house, but since it is you here, why ..."

Suzanne demanded that they stop talking about this. She had never intended to claim the house. Ever. And her mother! "Dika -- " she said, using Amadika's childhood diminutive for the first time, hearing it come out of her mouth without warning, causing her voice to catch, "don't you remember my mother?"

"The Little Boss, we called her," Amadika said.

"You did?"

Amadika nodded her head in embarrassment.

Well, Suzanne said, the Little Boss definitely wasn't coming back to Zimbabwe. None of them were. She spoke about her little house in New Portshead as if it were always her life's dream. She said this trip to Zimbabwe was only an opportunity to regain memories and relationships she had lost, not property. Already she had achieved more than she ever imagined she could: To find them here! To see Amadika again! And next (she wanted to change the subject entirely) she hoped that their group could help Robert and Sarah and their community.

Suzanne invited to Sarah and Robert to join the conversation, but they were too ill at ease to speak. Neither wanted to explain what had happened to them beyond mentioning Operation Murambatsvina; this clearly was enough to convey how desperate they were.

Samuel lowered his voice. "You say government has removed the emergency clinic there?" Without waiting for Suzanne to answer, he went on, "I am sorry to tell you that in this country we have embraced our failure as triumph. Our president won't change. As the people get weaker, he gets stronger. No one can help us until he and his cronies are gone."

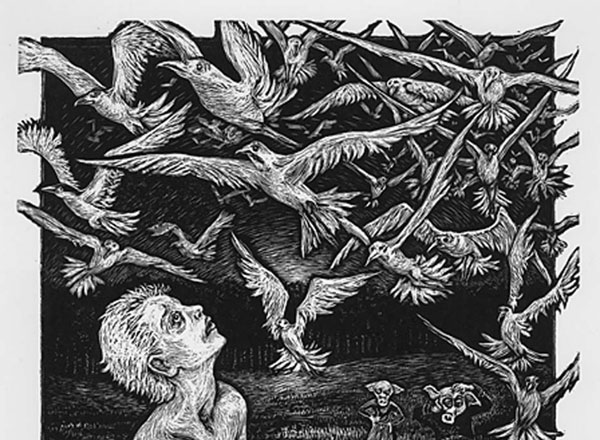

Amadika hummed and clucked and seemed to be pretending that she hadn't heard what Samuel had said. Suzanne and Tatenda and the grandchildren were listening to him carefully, however, while Robert and Sarah looked steadily at Suzanne through the yellow lantern light (it had fallen dark), silently imploring her to leave. She still felt the reverberating throb of her initial shock when Amadika called out her name. The whole of her life felt turned inside out -- look, a black girl named Suzanne had come into existence to take her place -- and she experienced an almost drugged sensation of seeing what had been going on within her all along. This was what she had lost and tried to recreate in her art.

03/11/2014

01:37:28 PM