Part VIII

Every minute Robert drove, paying no attention to the jarring impact of the rocks and ruts in the track he was following, seemed like an hour. Kerry told Suzanne that she thought she was all right. "I must be full of adrenalin," she said, twisting at the waist to demonstrate her recovery. Emmy was trembling, covering her face with her hands. Michelle and Sarah squeezed together on the passenger seat beside Robert. Had they really witnessed what they thought they had just witnessed? The mob was swift, angry, and violent. Men and women -- mostly men with the women spurring them on, and some women dancing, yes, there had been a wild spasm of dancing -- appeared and then disappeared, sudden and fugitive as lightning. They tossed the truck and car over, the metal shrieked, the glass broke, and Sarah had been a continuous instigator, shrieking exactly like the tortured metal, Sarah who was sitting with them now, her face drawn but her posture strong and erect.

"Bad, bad things," Robert finally said, breaking their silence. "Oh, my dear Lord, bad, bad things!" He pounded at the steering wheel and kept repeating himself, as if trying to exorcise the fears that lived in his throat.

"What will happen to those poor people?" Kerry asked.

"Oh, do not ask," Sarah said gravely. "Robert, hush now!"

"I cannot help myself, mama."

"Where are we going?" Michelle demanded. "I want to go to the hotel, I want to get out of Zimbabwe, I want to go home!"

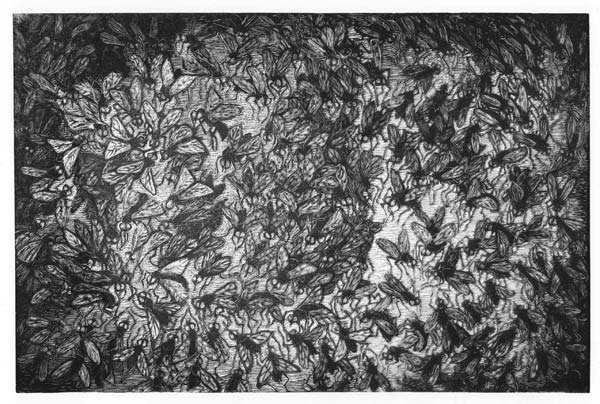

They had reached another dry wash and made their way to the fence line of a ranch where they settled into some tractor tracks. The sky Suzanne had seen the day of their arrival was gone, its celestial blue tarnished into lead. The rainy season would begin in a day or two. She remembered its weight and felt again how it made everything cower, the plants and trees and rooftops and people, pelting and drenching the world. As a little girl, she'd sat in her room and looked out the window and drawn little marks all over a sheet of paper. How many raindrops fell in a storm? How many marks should she make to replicate their multitude? Thousands and thousands, each naturally and briefly perfect. She spent forever drawing those marks. A downpour. A torrent.

"We're heading north," Emmy said. "Harare is to our right."

Robert said, "We will find a road soon, I am sure. I'm looking for one now."

Eventually they came to a road that intersected the fence line and that would, Robert said, enable him to circle back toward Harare. He said he was glad of that because he was low on petrol and suggested they head straight for the ICFC facility, where he could fill up his tank.

Kerry, however, already had been talking with ICFC on her cell phone, telling Crystal what had happened. Crystal said coming there wouldn't be a good idea right now. Richard and Geoff had been summoned to the ministry.

"Where am I going to get petrol then, ma'am?" he asked.

"I don't know. Let's figure something else out."

"The hotel?"

"No, Robert, I think maybe not the hotel, either. Just drive. We've got to think what would be best."

There was a discussion about what Crystal had told Kerry. Certainly the authorities would want to talk to them. In fact, the authorities might even (this being Zimbabwe) try to detain them. Should they go to the American embassy for help? But what about Suzanne? She was Zimbabwean. The American embassy couldn't help her; it might even make things difficult for her to return to the States. So they couldn't go to the embassy.

Impatiently Robert broke in. "But where then, madam? I can't make this car go forever without petrol. Someplace they don't look? Miss Suzanne's house, do you want to go there? It's on this side of Harare."

Robert meant the Vuamba house. Suzanne objected. She said the Vuambas wouldn't want to be involved in something like this, but the others seized on it.

"What alternative do we have?" Emmy asked.

"Just for a few hours," Kerry said. They needed a place where they could wait for word from ICFC and absorb what had happened.

"You mean we need a place to face the fact that this is over," Michelle said. "How could we possibly stay on after this?"

"Don't say that!" Kerry snapped at them. Was she panicking, or was she taking charge again? She didn't appear to know the answer to that question herself but was desperate not to fail. She reminded them why they were in Zimbabwe. "So let's think, really think. We can't commit to the first thing that comes out of our mouths. This is all a symptom of the need for health care, not the reverse. We just have to figure out how to make that case."

"To Mrs. Kahiya?" Emmy asked.

"To anyone who will listen!"

"No one's going to listen -- look at what happened," Michelle said.

Suzanne was right; going to the Vuamba house (that's how it felt now, their house, not her house) was not a good idea. Amadika, Suzanne and Tatenda received them with alarm -- four harried white women barging into their world, disorderly and disturbed. What refuge could they offer? Who could hide in Zimbabwe? Amadika called Samuel at the finance ministry. He rushed home in twenty minutes and listened in profound silence. Emmy was the one who described the scene they had fled -- the dire conditions in the encampment, the needy people, the unreasonable officials. There was nothing inaccurate in what she said, but Suzanne could see that it offended the Vuambas. Yet when Amadika tried to minimize some of the more disturbing things Emmy recounted, Emmy only became more graphic. Zimbabwe, she said, was in the grips of a dictatorship that was dying and wanted everyone in Zimbabwe to die with it.

"No cholera?" she asked. "What about the man we left in the tent? Wasn't that cholera? What about him?"

"Oh, my god, we just left them there," Kerry said, having just returned to the veranda from making another call to ICFC and learning the meeting with the ministry hadn't gone well.

"He was almost okay," Michelle said. "We did everything we could."

"Just wait until the rains hit," Emmy said. "That's when the cholera will really take off -- more standing water, more sewage flows."

Suzanne could see Amadika didn't like mention of sewage flows. She didn't like Robert and Sarah on her veranda. She didn't like any of the people with whom Suzanne associated. What had happened to the little girl who was her childhood friend, the one whose memory and return had been magic?

"Is it really as bad as she says?" she asked Suzanne directly.

Suzanne pictured her father receiving black guests in this house who surely told him things were so bad fifty years ago. For you whites, perhaps this country is paradise, Professor Mosel. But for us? Look at your films. What do they say? They say what we say: it is hell. On our side of the fence, it is hell. On our side of the road, it is hell. On our side of the city, it is hell. The Land of Zim: no fence in time or space between heaven and hell. "Dika, I'm not a nurse. I guess to a nurse everyone everywhere is a little sick."

"Especially when people are denied health care, food and shelter," Emmy said. "This country has collapsed."

Samuel cleared his throat, preparing to speak. Amadika raised her hand, warning him to moderate himself. "No, no," he said to her, meaning he wouldn't moderate himself. He was repelled by Emmy's candor and furious that Kerry had been conducting telephone conversations about this scandal on his property. "You ladies have taken great risks for noble reasons, I am sure. You have gone to a terrible place on a terrible mission. Should you have done that? This may disturb you, but I think what you did was foolish and reckless. And I think the nobility of your purpose grants you no impunity. In fact, what you've done was dangerous, and the way you conduct yourselves is dangerous. I wonder who can come to a place like Zimbabwe at a moment like this and rush to the bottom of a steep hill where many people have fallen and been hurt and dare cry out, 'These hills are terrible! There shouldn't be hills like this! They should be leveled, every one of them -- right away! Do it right away!' Can God do that? Is who you think you are, God in His heavens?" Samuel searched the women's faces for their answer, expecting none and receiving none. "If this is found out, that you came to us, what do you think will happen? Do you think the authorities will give me a medal?"

Suzanne realized that Samuel was angrier with himself than with them. He was saying he couldn't protect them, and he must be feeling what her father had felt, knowing that he was about to abandon his students and colleagues -- driven out in one sense; fleeing in another. But Samuel had no place to go.

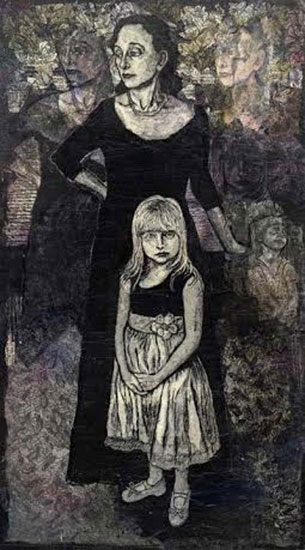

A little girl came out on the veranda, took her place between Tatenda's knees, and stared at her grandfather. Had she heard what he had said? It didn't matter. She could see the conflict in his face, his eyes bulging, his head tilted back so that he seemed to look down on everyone in condemnation. She was taking this all in exactly as Suzanne had taken everything in four decades ago, recording the confusion and tension, the sense that life beyond the veranda had intruded onto the veranda, and no one could drive it away.

Kerry simply surrendered. The uncertain waif Suzanne had first seen in her studio reappeared. She clearly felt helpless and defeated and had tears in her eyes as she apologized for the mistakes they had made. Seeing that his point had gotten through, Samuel accepted her apology with terse dignity.

"It is not that we do not wish you well," he added. "Certainly not that."

Pulling herself together, Kerry thanked him and all his family. She said it now appeared they had two options: take the next morning's flight to Pretoria or try to work things out with the ministry. She said ICFC strongly advised that they take the flight. But this wasn't a matter for the Vuambas to resolve, and she did not want to intrude any further. They really should go back to the hotel.

Robert timidly asked Samuel if he happened to have a little petrol he could borrow. Samuel said he did.

After their return, Kerry came to New Portshead twice. The first time she was alone. She wanted Suzanne to criticize everything she'd done wrong from the moment they got off the plane in Harare to the moment they got back on and flew away. Suzanne wouldn't do it. They struggled about this for more than an hour, just the two of them, Kerry trying to capture Suzanne's judgment and Suzanne pushing her away, refusing to cooperate, not wanting Kerry back in the Land of Zim with her. It was, on Kerry's side, the angriest conversation they'd ever had. She flew into a rage. She said horrible things to Suzanne. Played back to her many of her own self-criticisms: selfish, selfish, selfish. In a lover's fight, Suzanne thought, you heard these things, but they weren't lovers. It was the child power in Kerry, she realized, what a fury, what demands. I want to be your little girl, Kerry was saying. That is how this had really turned out. And Suzanne was saying no. She could not and would not give in. Her little girl, if her little girl existed anywhere, was somewhere else. But she didn't say this. She just said no. Over and over again, no. She was determined that nothing, not even Kerry, interfere with whatever was germinating in her, born and reborn in Zimbabwe.

The second time, Kerry brought Emmy (Michelle wasn't interested anymore) to try to persuade Suzanne to consider participating in another mission, this one in Uganda. She was calm and in control of herself again. Amazingly, she had managed to redesign her project and even increase her grant, making up for the lost expenditures in Zimbabwe.

Suzanne said she was happy that Kerry was going to give her vision a second chance.

"Well, if you're so pleased, why won't you come along?" Kerry asked. "It's still the same challenge: how do we convey what it's like to care for people in Africa? We need you for that."

"No, you don't," Suzanne said. "If your funders are still on your side after what happened, they must understand."

"But they're only guessing. They don't know. You know, you see things."

These arguments, now applied to Uganda, didn't reach Suzanne. She couldn't do what she had to do through or with anyone else.

Emmy saw this. She was quieter than she had been, chastened. "Kerry," she said, "let it go. We can do this without Suzanne."

"I don't want to," Kerry said.

"You have to," Suzanne said.

"But why?" Kerry demanded.

Suzanne shrugged, not letting Kerry rise up again and attack. She simply said she had to work; she felt that urgently. There were more photos from Zimbabwe than she remembered taking, more sketches than she remembered making, more images drifting in and out of her mind than she could hold in place and study and explore and record. She had to work. This was her. She had no choice. No amount of persuasion could change her mind.

For months thereafter she would sit down at her big worktable and lose herself in her thoughts, pushing them this way and that, seeing the memories behind the pictures, the perceptions within the memories, the things that were hidden, and the things that were right there in plain sight.

She made Samuel's face four times, each time more candid. She rendered the body she'd seen, one man and every man lying in the dust, over and over again. Then the line of people outside the tent... the woman who died ... the man at passport control ... Sarah's bag with the Bible inside ... Amadika on the veranda ... and finally, a full-length portrait of herself and a pretty young girl standing in a garden. Suzanne is staring off into space. The girl is staring right back at anyone who dares look her in the eye.

05/25/2014

06:09:32 AM