In early 1918, diplomat Valery Asimov returns to Skotoprigonyevsk, Russia, to rescue Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtsev, a woman he could only dream of winning away from his friend Ivan Karamazov when they all were young. He receives a rude welcome from Lisa Khokhlakov, informal mistress of the local non-Bolshevik mob, who envies and despises Katerina Ivanovna, a secret Bolshevik sympathizer.

Part I

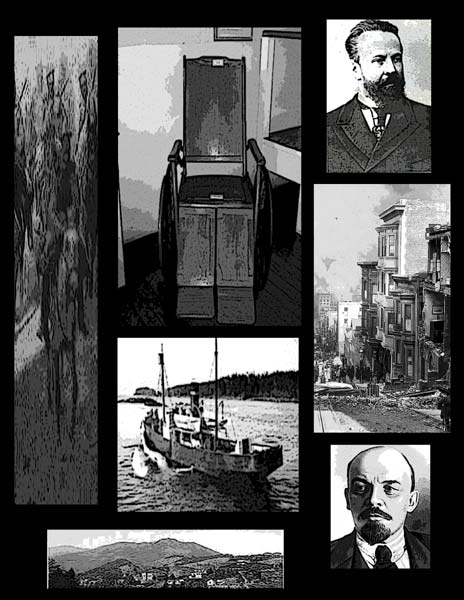

Valery looked into the room that normally served as the inn's tavern, but not today. The tables and chairs were stacked in the corridor leading back to the kitchen. There were no mugs, glasses, cups or plates to be seen. The room was packed with peasants, a few merchants, some women, three monks, and a priest. In the far corner on a slightly raised platform, an emaciated, gray-haired but oddly youthful woman sat in a wheelchair with a board resting across its arms. She used this board as a desk and wrote in a notebook while occasionally freshening her pen's nib with ink. She seemed to be listening more than looking. But she was listening carefully to the wheeling din, arguments wandering around the room like bad weather, now rain, now sleet, a clattering, drumming noise with no fixed center, no protocol, no order.

The heavyset innkeeper looked on from behind the bar. He had been dispossessed of his premises, but remained stuck with them. The angry way he folded his arms over his chest and leaned back against the liquor shelf epitomized the fact that no one "owned" anything in Russia anymore. Valery hadn't known things had gone so far so fast. Utopia, at last, but this was Skotoprigonyevsk! The peasants were as colorful and wrinkled as fallen leaves being blown around by a gusting need to be heard and understood. One old brute tipped his head back to have a good look at a merchant, eye-to-eye, beard-to-beard. A greasy-haired monk squeezed his way from group to group with pleading beneficence in his expression. "For the love of God," his smile said, but he was ignored.

Valery would have liked to sign the register, had his bags taken to a room, and then sat over a glass of wine and perhaps a piece of cheese. He had traveled all the way around the war from Madrid through London and Stockholm and across the Baltic to St. Petersburg and then down. Almost three weeks. He was exhausted both by his journey and the shock of arrival. As he was carted to the inn from the train station, he had not truly recognized anything about the little town he'd visited as a boy, lived in for a few years as a young man, and not seen in almost two decades.

None of it looked "as it was," or had he never really examined it, the plastered buildings, the rutted roads, the jumble of hills and twisting alleyways and odd lack of trees in a place surrounded by thick green forests? Twice he'd visited his Uncle Boris and been a boy in the dreaminess of Skotoprigonyevsk's summers. He'd had his first serious encounters with spiders, trout, Pushkin and Tolstoy here, the possibility that he was actually a Russian (which of course he was) first presenting itself to him in their poetry and prose. And then there were the mushrooms glistening in drawn butter, mushrooms by themselves and in salads and something he adored beyond words: mushroom pies, the taupe meat of these exquisite fungi resting lightly on savory crusts beneath the slightest sprinkling of grated cheese and crumbled toast ... followed by pickles and the cold jolt of vodka Uncle Boris made him drink when he was ten years old. "We won't be able to get any beer into you," he'd say, "but you're just the right size for my vodka." "His" vodka, precious product of "his" distillery that employed "his" potatoes and "his" special stream water and even "his" glass bottles, long necked and faintly dimpled.

Valery didn't remember the inn as having been as it was, but it couldn't have changed in a hundred years, the blackened timbers stretching across the ceiling, the wide oak boards underfoot, the thick plaster on the walls, chipped and gouged but solid, the diffuse light making the tavern room blush with a kind of silvery aura so that one felt one was seeking one's image in the back of a mirror not the looking glass side.

The woman in the wheelchair with her gray hair pulled tight back on her narrow head had sunken eyes, a deep cleft at her collarbone, and an odd way of seeming to spank the paper upon which she wrote, taking down certain points with a grim brio, although it was not clear whether these points emerged from what she heard or what she thought. She had thin arms that were covered with long sleeves. Her shawl draped down over her shoulders to her lap. Her skirts concealed her legs and shoes.

Although Valery had never met her, she could only be one person: Lisa Khokhlakov back in the wheelchair where Dostoevsky had first portrayed her with his love -- one supposed it was love -- of her contradictions. When she wrote something down, numerous disputants looked her way either in satisfaction or apprehension. Valery had heard once that women like her -- women who seldom ate, or more accurately, deliberately starved themselves -- actually lived longer rather than shorter lives. This seemed confirmed by the luster of her skin, which wasn't wrinkled, just tarnished a bit beneath those sunken eyes. She could have been a girl of thirteen, judging by her size, but of course she would be in her fifties. And the fact that she sat on the little platform in her wheelchair gave her additional moral stature, reinforced by her pen, which seemed oversized in such bony hands. That's the way the old schoolteachers commanded their charges, the better to see and be seen, "above it all" in the heights of knowledge and the mind. But there was no ramp, so she must have been hoisted there, and this suggested a familiarity and dependence -- a person who needed others but also a person whose needs moved others to help her. It had to be Lisa Khokhlakov!

He excused himself several times as he made his way to the innkeeper. Under the circumstances, he was too well dressed. Hadn't there been a revolution to do away with folks like him? One peasant leaned back and shoved him into another peasant. The man he fell against pushed him away. The innkeeper gave him a cautionary look: don't react. He didn't, simply apologized but not excessively with the unpleasant sensation of being in a prison yard when the inmates had been let out of their cells. They were irate, surly. The monks had florid, purplish faces, too.

One monk cried out, "What we grow and don't eat, we give to the poor, but we must eat, too!"

A babushka didn't respond to him directly. She simply called out, addressing no one and everyone, "They have eaten well for quite a long time, haven't they? And by what right, when we've all famished?"

"You, famished?" a lesser old peasant snapped. "What's in that fat belly of yours, gas?"

Valery asked the innkeeper if there was a room for the night. The innkeeper, fleshy faced and truculent, nodded.

"These don't sleep here, or if they do, they don't pay." He glanced pointedly at Valery's fine jacket, shirt and tie. "I assume you'll pay."

"Of course, I'll pay. What's going on here? What is this ... meeting?"

Without shifting his eyes toward Lisa Khokhlakov in her wheelchair, the innkeeper used the pronoun "she;" there could only be one "she." "She'll come and have herself hoisted up there, and it's not long before others will come here, then others upon others, what they call the soviet. The Bolshies in Moscow don't like her, but the Socialist Revolutionaries ... she's more or less their leader. Has been for years. Became one of them somehow. Believe me, there would be violence if I served them a drop, but I don't. I clear it all away, and there they stand yammering. What do I say when they ask who you are?"

Valery realized this was a civilized, well-meaning man. "You could say I'm a traveler. Why would anyone care?"

The innkeeper said they would all care, men who had never set foot in his establishment before -- wouldn't have a kopek for it -- the monks, think of them in a tavern! What would they be doing here? Saving souls? They were saving their skins. "And the gentlemen you see. What used to be their club is burned, so where would they go if not here? What once were their warehouses and factories, do you think they'd risk meeting there? The world doesn't know," he concluded. "The world has no idea."

Lisa Khokhlakov tore a page from her notebook. Everyone looked her way, Valery and the innkeeper included, alert to the rasping sound and tight movement of her claw of a hand. She held up the piece of paper and showed everyone that she had drawn a map upon it.

"Here are the monastery's fields," she said, folding and refolding the map to facilitate tearing the piece of paper a second, third, fourth and fifth time. She then asked for a hat into which she dropped the torn strips of paper. "And I see we have someone visiting us who has no place here, so why not allow him to pick out these strips of land and distribute them as he will. What do you say? Does anyone object?"

Did she mean Valery? Could she know who he was? He realized, uncomfortably, that she could because he had come to resemble his Uncle Boris. He wore the same luxuriant beard, and he was so bald and large domed and possessed the same inquisitive gray eyes -- eyes not dissimilar from his father's, of course, but his father wasn't the one Lisa Khokhlakov had known; it was Uncle Boris she had known, and Valery was like his return, a man of somewhat incurable intelligence and curiosity.

A priest, conceivably the archimandrite, objected. "We have never kept to ourselves that which was the Lord's nor have we worked our fields any less than anyone else. How can you put them on a piece of paper and toss them to the wind?"

"The wind didn't blow them into your hands in the first place?" Lisa Khokhlakov asked. "If we don't do something with what's ours, do we turn from the Lord to Lenin? Let him have them? The Bolshies don't run this town. Our soviet belongs to us."

"We could all share those fields," a thin peasant said. "Or we could put to work all these who don't work -- " he gestured at three or four merchants, pointing each one out with a jab of his index finger " -- and if they produced a grain or two, we could make our harvest reach every bare table all winter long."

"It's the Lord's land!" a monk cried out. "It's belonged to Him and through Him to you for hundreds of years!"

Lisa Khokhlakov said, "What Lord? It's two thousand years since he wouldn't fight to take from Rome what Rome had no right to in the first place. Now there's Moscow and they want from us what Rome wanted from them. The gangs will come; they're already coming. Feed us! Feed us! Can't you hear it?" She smiled, pleased with herself. "We didn't learn from Marx what religion is only to give it over to the new high priests -- holy Lenin and Trotsky -- did we? It's none of you that will own an ounce of that monastery soil, only some that will have to sow and harvest it." She held the hat up high with her gnarly hand. "'Mine' is no word anymore, nor 'God,' 'Lord,' or 'Jesus.' If this man -- " she meant Valery; she hadn't lost track of her intention " -- gives you a strip of paper, that land will be yours to share. Leave if you don't want it. Go away. But if you do, the next map I'll be drawing is one where your 'own' land falls in another's grasp."

Lisa Khokhlakov laughed girlishly, amused by the seriousness of the crowd confronting her and enjoying the impact of her words.

"I would rather not interfere," Valery said, his voice dry and unpersuasive.

"What are you doing here if not interfering?" Lisa Khokhlakov asked. "Aren't you one who once had his piece of this town and land with no claim but inheritance and went away rich? Aren't you Valery Asimov, nephew of old Count Boris, as he styled himself?"

Valery had never heard Boris style himself count anything and said so. "I'm here on a private matter."

"There are no private matters in Russia anymore. Russia was the czar's private matter. But Russia isn't his anymore. It's ours."

"I've long believed that myself."

"Then come here and give the people what's theirs. Take these monastery lands and distribute them." It was as though she were speaking to Valery alone and the dozens of people crowded into the packed tavern were statues or vases, or samovars. "You know this is how things are, don't you? What brings you here if you don't know that?"

He understood that when anyone dared thwart her, she redoubled her attack, but he didn't want to become her accomplice. "Do it yourself. It makes no difference if chance works through your hand or mine."

"Is that what Ivan Karamazov taught you?"

The name "Karamazov" caused a stir in the room.

Lisa continued on "He had a younger brother who was a believer, but wasn't Ivan the one who told us God couldn't be God if he'd let the children suffer and die? So then who keeps them from suffering and dying? It's the folk who do or they don't. It's not the ones who talk, not the ones who chant and pray. I'm not chance, am I? I say take these lands and give them to men who will work them or lose them. Spare the children. Make these men work. Isn't that what your friend Ivan taught you?"

Valery made his way through the room. Piece by piece he withdrew strips of paper from the hat that now rested on her writing board beside her ink pot and handed them to six individuals, his eyes not meeting theirs and their eyes not meeting his.

The last man to whom he handed a strip of paper was a monk. A round of complaints and cries burst forth. What justice was this? Who did he think he was? The monk, a man no different from any other man except for his garb, took the piece of paper and crumpled it in his hand not in disdain but so that no one could pry it out. He was called Michael and kept a hair shirt under his robe. Suddenly he was struck on the back of the head. Another fist reached his cheekbone. Two of his brother monks pulled him away. The scuffling lasted perhaps twenty seconds before the three monks and archimandrite escaped from the room.

#

An hour later, Valery heard a wheelchair rolling down the hallway toward his door. Then a rap-rap-rap. He lay on his bed, his coat, vest, and collar removed, staring at the low ceiling. Had not unpacked his luggage or pulled back the duvet. Simply opened the window and collapsed.

"You're in there?" Lisa Khokhlakov called to him.

"Yes, I am. The door is open. I haven't latched it."

"Haven't latched it!" she cried, wheeling into the room. "Now why wouldn't you do that?"

He had swung his legs over the edge of the bed to sit up. "What would be the point?"

The two of them confronted one another, Lisa enjoying herself even though she appeared tired, her head lolling a bit to the side, resting on her left shoulder.

"No point at all," she laughed. She didn't have her writing board across her lap. Valery saw that it had been slid into a kind of pocket that hung off one of the arms of her wheelchair. "Here, help me out of this," she said. She raised her arms, indicating that she wanted him to pick her up by the armpits and deposit her in the wooden chair by the window. He could feel responsiveness in her legs as he did this. She wasn't paralyzed, only weak. Did not smell terribly clean. Mousy -- a mildewed unwashed slightly acrid scent. Perhaps the scent of urine.

She began to speak. For someone who had banned certain words and deprecated the use of others, speech came readily to her. Before she was finished, she had filled the whole room -- it wasn't large, to be sure -- with speech.

"I did see you once or twice. I couldn't have been very old the first time. Maybe I was six. How old are you? Fifty? Then you were ten, I would suppose. And twenty-one or twenty-two when you came back to sell off what you inherited from your uncle? I looked out the window and saw you and sent my maid to find out what you were doing. You weren't doing anything. Or that's what the stupid girl said. I remember it quite clearly. I gave her a ruble every week for being so stupid. My mother detested me doing that. She asked whose soul I thought I was saving, the girl's or my own. I said, 'Haven't you heard? There are no souls. To be souls there would have to be a soul-keeper,' and there was no soul-keeper. That scandalized my mother, and she was scandalized that I complimented my stupid maid for telling me the truth: you weren't doing anything! You'd come to take over Count Boris's estate. That certainly was nothing. And then you began calling on Katerina Ivanovna and Ivan Karamazov, teaching him English, was it? More nothing. My maid had no idea what English was or how anyone could talk it. Two rubles for that. I said to my mother, 'When you die and I have everything, I'll give it all away to the stupid people here.' I told her I'd begin giving her rubles if she didn't watch out. Oh, but we fought! And before I knew it, why, she died. I hadn't given her a thing, not that it would have helped her or me, but still ... I didn't have any Karamazov -- Alexei had left me, hadn't he, even if Kristina Ivanovna had hers? What did I have left? Skotoprigonyevsk! And I hated it and wanted it different and my plan was to tell her I was buying my freedom from the serfdom of being stuck here as her sickly daughter, but I never had the chance. She died so fast. Wasn't it a good idea, though? Shouldn't all children and all people give one another whatever they have? Isn't it better than murder and war, just admit you can't hold onto anything anyway?"

Valery wondered if she really wanted an answer or was simply too tired to rant on by herself, but no matter her physical condition, she was a curious mixture of spring water and lye. She could cool and soothe someone if she wished, or she could burn off his ears and skin.

"I can't think of much that isn't better than murder and war."

"Have you really reflected on this?" she asked.

"I live in Spain, so I don't have to look at it day in and day out, but since 1914, yes, I've reflected on it. I've read about the war and I have many acquaintances and correspondents and know lots of fugitives, and they tell me what they've seen and experienced, and the Spanish lose shipping to the Germans, of course."

"And lost the Philippines and Puerto Rico and Cuba to the Americans, right? The Spanish aren't any good at war, so it's better they're neutral. I should send the king of Spain a ruble or two, don't you think? He's as stupid as they come."

Valery laughed. "It couldn't hurt."

She clapped her hands, delighted by his response. "You know, I haven't many left, and they're going fast. Now we're in a situation where everyone is being stupid. They all talk about no more Czar and relate it to something they thought or did, or something someone else thought or did, and they never ask themselves whether it wasn't the Czar's doing, not theirs. There aren't any standards any more, only me and my rubles."

"And things like your map."

"Didn't you like that?"

"No one will ever forget your map. That will live on. You took so many hectares and translated them into a sketch on a piece of paper and then tore them up like some giantess and voila, see how they became something they'd never been before -- the people's farm!"

Lisa liked how he put things. "You'll never get a ruble from me. You're too smart!"

"Even when I gave the last scrap to the monk?"

"Oh, that was brilliant!" Lisa settled herself a bit to phrase exactly what she thought in her most wicked way. "Here's what I thought: with that gesture you showed no pity. No, what you showed was a quite brilliant disregard for Brother Philip's erstwhile status. You didn't give him that land as a monk; you gave it to him as a man. Skewered him with it. Made a Cain of him with it. There he stood, separate from his brethren, on a scrap of land that couldn't be his. Just what the Lord did to Cain."

"But you were the one who did it to Brother Philip -- making the land not his."

The lye seemed to flow in Lisa's eyes. "Would I wait for the Lord to do it? Rather slow fellow, that one, isn't He? Look about you. The earth is blood, all of Europe and all of Russia is blood, and that monastery land is drenched in it, and now we'll see how these idiots dry it -- or if they keep it wet. I think they'll keep it wet, don't you? Some will do it with sweat and tears, but most with blood. They'll fight over it. Now the seal is sundered and they'll all run through it, each grabbing what they can get."

Valery considered the broader meaning of her words. "In a sense, as you say, all of Europe, not just Russia, is this way."

"I don't give a fiddle for all of Europe. I am here in Skotoprigonyevsk, not there. I can't be like you, wandering the world. I'll never go to Madrid. I'll never even go to Moscow."

Did she mean she wouldn't go to Moscow because she was so enfeebled, or for some other reason? He let that go. He said that for many years he had not felt he was in a given place simply because some people called it a place and gave it a name -- be it the name of a city or a country. He used to think London was London and knew how to recognize it as such, or Madrid, or New York, or Stockholm, but he took these things more as provisional premises now. For him that was the essence of the Revolution and the role he had played in it.

"What role?" she asked.

"I've kept people informed. I've put people together. I've tried to make good use of my time stoking the crisis."

"This is my throne. What do you think?"

She shied away from the word crisis. The spring water came back into her eyes. "It's much simpler here in Skotoprigonyevsk," she said. "Everyone is carrying on when all we have to do is temper ourselves to our actual place, actual population, actual fields, factories, weather, all that." She gave him a little history lesson. Long ago there was Kiev, then Muscovy, then you had czars and czarinas, then nobility and police and on and on. "I call it the humiliation of the ruble, as you would imagine." Capitalism, that's what it was. She taught reading and mathematics in the day, socialism at night. A third person looking on might have taken her for the worldliest of souls and him for the least worldly, most naïve. She said she had to give up school teaching but never socialism. Now lots of things had happened in Skotoprigonyevsk but nothing took positive shape until she came to the inn and set up court in the tavern. "This is my throne. What do you think?" She reached over to smack the wooden arm of her wheelchair and then asked him to put her back into it, which he did. He realized she was terrified and furious. This had been a performance that cost her enormous effort. If he'd gone off with Ivan Karamazov, what did he know about Alexei Karamazov, whom she had loved in a way that perfected her contradictions? But she couldn't bear to ask him. Suddenly she was frightened. She wanted to get away from him.

"I think," he said, "that if there must be a throne, then a wheelchair would be a logical candidate."

"All the czars and kings and emperors in wheelchairs, you mean?" she laughed.

"Something like that."

Why, he asked himself, would she have been a schoolteacher? Because Alexei had loved children, and she had loved him? But she didn't love children and couldn't have them, so that couldn't last, Lisa looking at young faces already as full of moral disfigurement as their parents.'

She pushed her wheels toward the door of his dreadful room. Everything creaked, the wheels, the floorboards, the door itself. She looked up at him.

"Do you realize how little time you have to get Katerina Ivanovna out of here?"

He'd been thinking about nothing but time while he'd been wangling his way onto ships and trains and carts from the heart of somber Madrid around the coasts of Europe and down into the rutted evil ditches of Rus Materna. He'd sent his telegram, asking Katerina Ivanovna if all was well and should he come to visit, and she'd telegrammed back -- he still had the yellow slip in his vest pocket with the strip of an answer pasted on it -- "Thank you, no. We're well." And that simple, unbelievable rebuff in the context of all the terrible news he was receiving set the clock ticking in him, but it only ticked the way clocks and hearts and dripping water faucets ticked, it didn't tick the way things began to tick now, in Lisa's onrushing look, making him fully aware that Katerina Ivanovna's pride, which had sealed her in silence so long, would make his job necessary but almost impossible. The two women were the opposite sides of the same hard coin, queens eternally stamped on the Karamazov brothers' endless appeal.

"Not much, I would suppose."

"A few days? Even tomorrow may be too late. She claims she's some kind of Bolshie, which is the best way to insult us. Let the Bolshies protect her then."

She wheeled herself down the hall to the head of the stairs and rapped against the wall. Valery stood watching. Two men clambered up the stairs. They picked her up, wheelchair and all, and carried her away.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.