Valery Asimov hastens to Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtsev's house to assess the peril in which she lives. Skotoprigonyevsk does not resemble in the least the town he knew as a boy and young man. Her life is a shambles; her future is dubious at best.

Part I (continued)

It was only eight in the evening, not so late, though of course he hadn't eaten. "But I'm not here to eat," he said to himself out loud. Then he added, ironically, "I suppose."

He walked past the empty tavern room into the empty street and knew where he was going but did not feel he did. Directions were one thing -- go along this block, turn right, follow another block and turn left on Main Street -- but feelings another. He had meant to arrive, recover, compose himself and then go to Katerina Ivanovna in a frame of mind that was open to her. Travelers had to realize that people didn't see things as they did. People knew nothing about a traveler's observations, fears, and little mental rehearsals of what to say after hello, avoiding the faux pas of assuming that what one saw and heard while traveling was more important and interesting than what one experienced simply living in a place where everything was as everything always had been, the seasons, the harvests, the endlessness of Monday followed by the same thing on Tuesday.

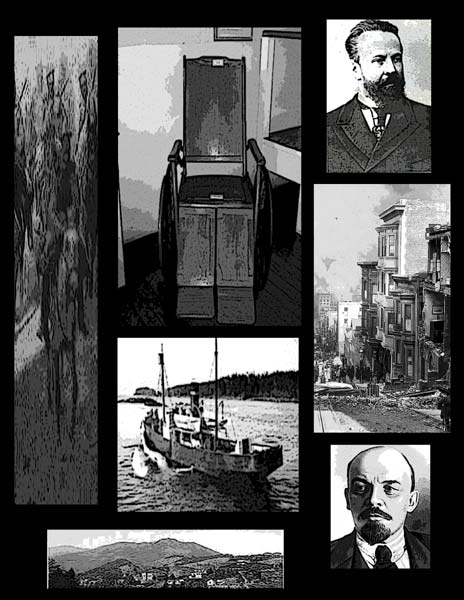

Nothing in Skotoprigonyevsk was as it had been, nor anything in Russia, but he wasn't the person to arrive at Katerina Ivanovna's doorstep to tell her that. Half the gas lamps were not lit, and Main Street had the look of needing to be laundered; it was murky, dirty, rumpled. When he forced himself to really look, he saw people scuttling along in the shadows. Who were they? He'd never known. That was the truth. During his boyhood he'd taken the love Boris's retainers had for him as something he, Valery, need not reciprocate. He'd been a little Boris on his visits to Skotoprigonyevsk, not a little Valery. He'd regarded the cook, Katje, and the butler, Nicholas, and the housekeepers, Marie and Sonya, and the stable crew, whatever their names had been, with the same bemused bonhomie as Boris, virtually appropriating Boris's dreamy smile and the way he handled his knife and fork and slurped his tea. Boris was easy to imitate, nothing like Valery's father. You didn't have to know history to be like Boris. You could put yourself first because you didn't take on the planet, time, nation states, philosophers, different languages ... all the stuff that was the essence of a diplomat's life. On those summer visits, partly spent here in town and partly out on the estates, Valery literally had no idea that there was any such thing as Karamazovs anywhere in the world, much less right there in Skotoprigonyevsk. Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov and his two wives and three sons, their schemes and scandals? No. Not in Boris' life and so not in little Valery's life. The point, Valery now realized as he walked along Main Street toward the yellow house where he ultimately had taken refuge once he'd become Boris's heir was that Boris did not want anything about Skotoprigonyevsk to suggest to his young visitor that it was lesser than what he knew in his father's life. The two brothers enjoyed a loving sibling rivalry. Valery's father left Skotoprigonyevsk, Boris stayed in Skotoprigonyevsk. Boris was richer than Valery's father, and his life, if not the life of a nobleman, wasn't the kind of life you already found in Dostoevsky's earlier books. He wasn't surrounded by murderers, revolutionaries, spiritualists ... the cavalcade of protagonists in Dostoevsky's thinly veiled fictions ... the actual people -- Dmitri, Ivan, and Alexei only some of them -- who made Skotoprigonyevsk a passionate place ... almost a field of battle. Boris wasn't about to introduce such "neighbors" to his darling nephew, but he was too acute a man (a man who could take in every word he happened to hear a Chekhov utter and record them with exactitude) to not know there were dark affairs afoot in dear old Skoto that had nothing to do with mushroom pies or icy shots of vodka.

Valery came to the corner that would lead him, if he let it, on a detour past Boris's townhouse with its deep porch, brick facade, and slate roof adorned with conical turrets, the left one jutting up from Boris's room and the right one from Valery's room. He could walk there, have a look, and retrace his steps in three minutes. He had lived in it as a young man after Boris's death. Before Katerina Ivanovna asked him to come speak English with Ivan, he had sat there realizing his life was going nowhere and that Boris's life had gone nowhere. He knew there must be more to this provincial town, but how could he touch it? Then he found out. He sat there reading The Brothers Karamazov one week, unable to put it down, knowing Ivan Karamazov lived nearby and the next week he met him. He actually met Ivan Karamazov and Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtsev!

"But the point isn't going back into your former life," he said out loud again, "it's going forward into Katerina Ivanovna's present life and ... "

The sound of her name caused him to quicken his pace. He reached her yellow stucco house before he could say another word.

#

She sat beside him on a red velour sofa, holding his hand, her hair gone gray and dry, her features fallen, her manner hesitant. He did everything he could to let her be the one to speak even as the room -- its two decades-long sameness! -- its elephant hunt, prints of Kazakh mosques and Scottish moors! -- overwhelmed him and he found himself wondering how he could undo everything she was telling him.

Her country estate was gone; the manager had been killed, the family driven away. Day by day her money became worth less and less. Never mind sending Lenin money anymore, there was little she could give her servants, Marfa and Pyotr, except food and lodging. What they suggested made sense: have them invite everyone to whom they were related to live in the house before it was expropriated and she was instructed to move.

"They've 'summoned' me, or that's what Pyotr says, although I haven't received any such summons. Do you know they hate the Bolsheviks in Skotoprigonyevsk, and that's how they see me? Lenin is said to be 'in power,' and they reject that. There's no fighting here, yet ... How can this be happening, Valery? I would like to know what Lenin intends. I've written to him three times, but if I went to Moscow, would I come back and be able to walk through that door?" She pointed to her front door, where she had greeted Valery, the two of them standing stock still in utter shock, dismayed by one another's appearance, each overwhelmed with emotions of inadequacy and perhaps Lisa Khokhlakov's favorite pejorative, stupidity. "The house would belong to someone else. Marfa and Pyotr have given me an ultimatum: Either I invite their relatives here, or they must leave. They can't afford to be associated with me. They don't want to see me put out. I counted it up. Over seventeen years, I gave Lenin 107,000 rubles. Can you conceive that? We met this young man and recognized his brute genius and you and Ivan went off and I returned and ... you wrote Ivan was dead ... and then this revolution ... What could I do? What could I say?"

She was like someone he knew in the recesses of his soul and someone he didn't know at all. This woman a dozen years older than he ... woman whom he had utterly loved. Wonderful and unattainable and more sustaining to him than his father or uncle or anyone else -- even Ivan, even Christina. At fifty-two, he was old enough to tell himself that now. There was no point in deceiving himself. Yet her desperation harmonizing with the flickering oil lamps (there apparently was no electricity, nor much heat) brought him a certain factual joy for which he felt guilty. Look, Katerina Ivanovna was holding his hand and he knew he was dear to her!

"Oh, this terrible war," she said, leaping over the news she gave him that his uncle Boris's house had been occupied months ago. "Half the young men went off and died. Then they sent for the next half. Well, who would do the farm work, reap the harvest, tend the animals, chop the wood? It's been years now."

Years like falling from a kind of mountaintop and at each painful point thinking the pain couldn't go on, there couldn't be any more falling, and yet there was.

"What on earth is a world war?" he asked, simply to let her know she wasn't mad. "Now we know."

"Does Lenin answer you?" she asked.

"I haven't asked him anything."

She waited for him to go on. He wanted to talk about something else, but she wasn't ready for that. "I have always done it through intermediaries," she said. "Is that what you do?"

He said that for years he'd written what he saw, heard, and thought and presumed at least some of it reached Lenin. "But I really don't know. I had an address in London, then Zurich ... " He could see she wanted him to praise Lenin for his burgeoning triumph to which she had contributed so much. He could see, or was afraid he could see, that she somehow loved the man. " ... I couldn't play an overt role, of course. I couldn't belong to any party."

"No, nor could I."

"Does anyone here realize what you've done? Lisa calls you some kind of Bolshie. The intermediaries you used -- who were they?"

She smiled the way one might smile at a child as one told a fairy tale. "They appeared out of nowhere and returned to wherever that is. Here. Look." She opened a small black bag that was fastened to her belt and extracted a notebook with a soft blue leather cover. There were pages and pages of lists. On each line she had entered a date and a number and a place. The date was when she had transferred the rubles whose quantity appeared next to it. October 23, 1906 ... 150 ... Skotoprigonyevsk; January 27, 1907 ... 200 ... Moscow. And so on, including large numbers. On April 4, 1911 she had given a revolutionary troll 2500 rubles in Moscow, where she had been told to travel. That was the last item in the list. She had not seen Lenin since London, 1903. She had not received any report of what had been done with the money. Once, she said, she was asked to store several cartloads of newsprint in her cellar. It was removed over a three-year period.

"Surely Pyotr and Marfa knew this," Valery said.

"It wasn't discussed. It simply was done."

"But to bear witness to your sacrifice and thereby help you -- they wouldn't be of any use?"

She shook her head. "I defend myself by having said that we couldn't continue living like insects under the pavements of palaces. No one can say I have not said that for many years."

"Would Lisa Khokhlakov have heard you say that?"

"I have not made it my business to be heard by her. She doesn't like anyone, but especially me. What unites us divides us. We make each other miserable, loving two brothers and losing them both."

They had not met since Ivan's murder nor had Valery written to Katerina Ivanovna the details. They would have to go into it but not now. He had to tell her what Lisa Khokhlakov had done in the tavern and said to him privately afterward. Katerina Ivanovna astonished him by ignoring her own interests and focusing on the question of the dismembered monastery though she said that if she were still religious she would convert to Judaism.

"Why is that?" he asked.

"Because they wait with no answers. Ivan said that Jesus failed in asserting the possibility of God because of all the children who suffer. The Jews don't pretend to be so smart; they don't judge God or accept Jesus ... they wait ... isn't that wonderful? But as I say, I'm neither Christian nor Jew and I wouldn't put a monastery between human beings and the fields they need to sustain them."

"So you think Lisa was right?"

Katerina Ivanovna smiled at Valery's use of the word right. "She's like God now, isn't she? No one can demand she explain herself. She's like the future because she can't be foreseen."

"God. The future," Valery said, puzzling hard for a moment. "Perhaps you and the Jews are right. Everywhere we look, at Lisa, at Russia, at the Bolsheviks, at the Whites, at Germany, at England and America ... we don't know ... "

She kept holding his hand. Had she made the most terrible mistake, returning to Russia by herself and not going on with him and Ivan? It was heartbreaking, really. She had been too proud and realistic to do otherwise. Valery would be some kind of diplomat. Ivan would be some kind of journalistic propagandist, but what would she be if she went with them against Lenin's wishes? The fine lady in the way? She'd said no, here's another path -- this young revolutionary they met in Berlin says he needs me in Russia and given me my role and I will play it on a different portion of the stage ... just beyond the turmoil and the unforeseeable demands of excruciating time which Lenin somehow overcame, rising every morning believing that he had urgent things to do ... writing letters and books and statements and coordinating meetings and conjuring dangerous plots, always drawing on money Katerina Ivanovna and dozens like her gave him and gave him and gave him.

"Have you had supper?" she asked.

He said he had. She said she knew he was lying because there was nowhere to eat, certainly not at that inn. He asked her what she knew about that inn. She said she had gone there herself once, desperate for something to eat, and been told ... well, he knew what she had been told.

"Do you mean you have gone hungry?" he asked.

"Valery, we've have been hungry since 1914!"

She had some cheese in a piece of wax paper and two salted fish filets and there was a little mustard and a roll but no butter. When they had been together, Ivan recovering from Dmitri's trial and Valery pink-faced though balding, there had been sherry and pea soup with a dollop of butter floating in the middle of the bowl followed by roast beef or veal or duck and hot rolls and everything else ... the condiment tray, all the pastries, the candies, the cognac.

Her plan was that they would eat the fish, cheese and roll English-style, or what she thought was English-style: as a sandwich. They took a kerosene lamp into the pantry and she put the food on the table and showed him how they would slice the roll, spread it with mustard, insert the filets, one in each piece of roll, and top it with the cheese.

They weren't talking about anything as they did this, only doing it, which was an immense relief to him, and he could see it was an immense relief to her as well. The food, and even the water they drank, made them smile.

"Silly," she said.

He wanted wine but didn't say so. He imagined the effect the wine would have on him and made do with that: just what he could imagine. That gave him courage, which he let build a bit. How would he approach this? Would he ask her what she wanted from Lenin? Did she want her house and something to eat and credit for what she had done? Or did she want more elemental protections, some kind of writ: whatever happens, she is not to be ... what? Physically harmed? Or did she want a role? Hadn't she earned that right?

"I just wonder whether playing musical chairs with our houses ..."

"Where are Pyotr and Marfa?" he asked.

"They say they won't stay here until I agree everyone can come."

"You mean you are alone tonight?"

"I have been alone for some time."

"Why couldn't everyone come?"

She wiped her mouth with her sleeve. Astonishing. He quickly pulled out a handkerchief and gave it to her. She patted her lips needlessly because the sleeve already had done the trick.

"I know this isn't my 'property' anymore. I just wonder whether playing musical chairs with our houses ... is that how we build a new society?"

Her lips weren't beautiful anymore; they lacked life although they had acquired a newly expressive line, a line of having been defrauded. He could imagine kissing them but these were frank lips and her eyes, encircled by a filigree of wrinkles, were frank, heavily-used eyes ... eyes that would be difficult to excite ... if not impossible. He could say let's stop talking about everything and especially about Lenin and think through the way in which we will leave Skotoprigonyevsk and go to Madrid, where I will conclude my affairs, and then find some place just beyond the border of the war ... and she would regard him with the weight of the years that had passed and crush him with it. He knew she would.

He said, "If as you say there is some kind of proceeding that will be directed at you ... "

"It already has."

"Written or unwritten?"

"Unwritten!"

"Would it be better to precipitate it or await it?

"Do you mean treat Lisa Khokhlakov as God or not-God? Is that what you mean? If I wait, she is God. If I poke back, if I challenge, if I step forward and say to her, 'You are not God because if you were, you would be a mystery,' she'd become angrier than God. Her Social Revolutionaries want control of Skotoprigonyevsk and my Bolsheviks don't exist here ... nor do I. It's all been secret. Hidden. It's hidden still."

He thought of her as a fish he wanted to catch. Sometimes this helped, taking the woman out of a woman and regarding her more neutrally. "You're not given credit for anything?"

"They held it against me that I did not resist the scavengers and requisitioners from Moscow so they let it be known that my lands ought to be the first ones taken away, which has ruined them."

"How could you have resisted?'

"Precisely. I couldn't. Pyotr says we could grow things here." She gestured over her shoulder in the direction of the rear garden where Ivan had sat so many years ago. "I told Pyotr to plant things then. He said what was the use if we'd lose the house if I wouldn't let everyone move in."

There was always something more, as he had anticipated, recognizing that the traveler brings no news equal to the homebody's infinite actuality. Be patient, he almost told himself out loud.

She gave him another example: "I did not resist her edict to seize my lands, either. I said I had not bought those lands; I had inherited them. Who was I to hold onto them in the face of a higher need?"

"Where and when did you say this? Did you have a confrontation?"

She said she had no use for confrontations and instead had focused on scavenging and bartering for the three essentials of her life: food, lamp oil, and coal, the latter of which she had not obtained at all in recent months. "There wasn't any confrontation because I wouldn't be in the same room with her. Look at my shoes!" She pushed her feet out from under the table so that Valery could see her battered, patched, worn-out shoes.

He felt he shouldn't have enjoyed his fish and cheese sandwich so much, thinking of how she must have demeaned herself to obtain it. He had just consumed her breakfast and lunch for tomorrow.

"I am saying perhaps there should be a confrontation, and if there were, I would help you."

"How would you help me?"

"Or we could simply leave," he suddenly capitulated. "We could go to Madrid. We ... "

"Leave? I don't want to leave! I won't leave! No, no, tell me how you could help me. What could you possibly do?"

The issue, he realized, was that when she pressed him personally, he was a coward because he loved her and feared for her so much, but he had to get through that. "I could be your advocate. I am trained in these things. It's my life. When no one knows who I am and I have no place ... that's the permanent condition of a diplomat, working yourself into things where you don't belong."

"But to what end?"

She didn't think he was a fool; she simply didn't know what he was talking about.

He threw out a wild idea out. "Let the beginning of the end be me being the first one to stay here with you."

She liked him saying this well enough to scold him about it. "You should never have gone to that inn in the first place. Now you've been compromised."

"I haven't been."

"She's made her mark on you."

"Made her mark on me?"

She astonished him. "Yes, like a dog. Urinated on you. I could smell it when you walked through the door."

"Well ... " He didn't know what to say. "Then that's progress, isn't it? She exists! God doesn't smell; Lisa Khokhlakov does; ergo, she isn't God!"

#

But if he was to stay, even for a night, it would have to be in the room where long ago Ivan had lived, and of course, Valery had never been there. He'd been in Ivan's bedroom in London; they'd shared hotel rooms in New York and Washington; they'd traveled across the aisle from one another in the train that took them, ultimately, to San Francisco. But Valery knew he'd find it exactly as it had been, untouched since he, Ivan, and Katerina Ivanovna left for their ten days in Berlin that turned into a lifetime and there met the bold young man, Ulyanov, who would become Lenin. And so it was, illumined by a single oil lamp, the prosaic silvery green bedspread, the shelf of books -- the Odyssey, Das Kapital, Don Quixote, volumes of Shakespeare in Russian, A Hero of Our Time, and the book itself, the book of all books: The Brothers Karamazov. It actually stood there, or slumped there. Had it been read? He couldn't tell. None of the books appeared read for Ivan would sit with a book in his lap, look straight down, and turn the pages as if they were the wings of a butterfly -- that delicate! And he, Valery, was turning these pages the same way, searching for ... "My God, I'm looking for myself!" he whispered. "Where am I?" He looked up at the molding between the walls and the ceiling, over at the sadly sagging purplish curtains, down at the braided brown and yellow piece of carpet, over at the russet chair, where Ivan would have sat when he was being very private, and probably very depressed and confused and not sure, in the earliest days after Katerina Ivanovna brought him home from Ward 6, that he had it in him to go downstairs. But no matter how intensely Valery studied this little bedroom and pictured his long dead closest and dearest friend, the man whose gray temples and chuckles and sinuous quality of thought entranced him, he could not find his own image. It was as though when all was said and done -- even before all was said and done, with so much more to say and do -- he did not really exist.

"Valery Asimov," he told himself, "this looking glass has done you in."

Then he saw her face next to his in the mirror above the dresser with its ivory knobs.

"You've got to tell me what happened," she said.

"It would take all night."

"I don't care. Tell me! You've got to tell me how he died and what happened to Mitya and Alexei and the woman and the children!"

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.