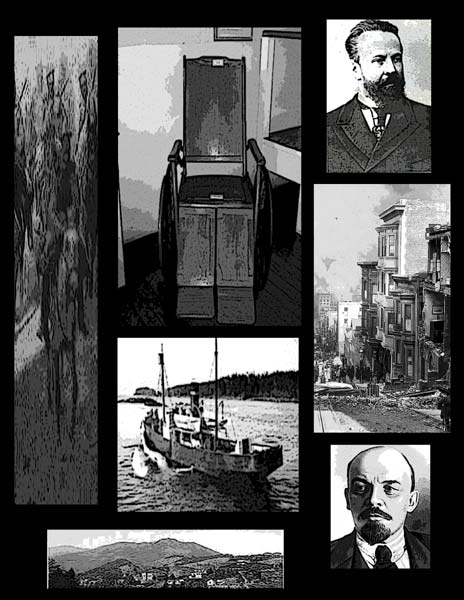

Valery obtains an audience with Lenin, Trotsky and Dzerzhinsky in the Kremlin. Will Lenin help the woman who over many years secretly sent him most of her fortune?

Part IV

Moscow. March. 1918. Valery did not care for the place, the month or the year. The month and the year were ineluctable if one were alive -- something he thought about now, one soon might not be alive -- but the place? Moscow had never been ineluctable before, yet now Lenin had imposed a new capital on an old land, spurning the beautiful bravado of Peter the Great's grand metropolis for Russia's stolid core, retreating to its greatest strength, the great nyet that withstood Napoleon, was burned and yet lived, was frozen and yet lived, saying nyet to everything, enduring the unendurable with that one fierce word ... nyet, nyet, nyet ... And here he was, making his way through escarpments of snow seemingly fallen centuries ago, holding onto hope in the face of the forlorn folk wrapped in fur, leather and wool, passing by the crusts of old buildings whose masonry and windows were in disrepair, the empty churches, the remnant of a hacksawed nation that had just surrendered its limbs -- Ukraine, Belarus, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania -- in return for a peace with Germany in which no one believed.

Brest-Litovsk! That's what the newsstand journals headlined: The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk! Where in hell was Brest-Litovsk? Valery almost reeled as he read the reports. He didn't know any of this. Was it good, Russia out of the war, just like that, after so many years of sacrifice? He felt with his back -- literally, as if his back were a sensory organ -- how much the people shoving behind him hated this retreat, these losses and unrequited sacrifices, but to him it was expedient and sensible. Look at this country. How could it keep fighting a war? It couldn't. Lenin was right and realistic, even if Trotsky was outraged.

He hailed a cab and asked to be taken to the portal of what now was called the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, a place he had never visited, had no idea where it was.

"Diplomat?" the driver asked, his accent a murky but musical Georgian version of Russian.

"Yes, I am."

"One that gave us up to the Krauts?"

"No, I am Russia's ambassador to Spain." Or was he, he wondered, not having been able to determine, in recent months, who or what he represented.

"What are you doing here then?"

Valery didn't answer, realizing he'd already said too much. Who would have a respectable taxi, petrol, and a place in the queue? And so many questions? Someone he shouldn't trust.

#

He couldn't go to the Kremlin and present his card, asking to see Lenin, but he could come here, sit under this chandelier and wait to see Georgy Chicherin, the deputy acting in the angry Trotsky's place. Already things looked right and wrong. Right for diplomacy -- the lavish carpets, the high ceiling, the absurd pompous palatial space -- and wrong for a socialist government that did not recognize the concept of statehood because all workers everywhere were one. Chicherin, too, would be right and wrong, also nephew of a Boris, but a more famous Boris than Valery's uncle Boris, fluent in many languages, expert in history, music, philosophy, and literature, and wealthy (much wealthier than Valery.) What kind of commissar of "the people" could Georgy Chicherin possibly be?

They didn't know one another but they knew of one another and were of the same class and embraced and kissed, and Chicherin apologized for almost a minute that he'd kept Valery waiting as he led him into his private office where they sat knee-to-knee.

"What are you doing here? I thought you were in Portugal. No, Spain! My God, it's good to see you. You're indispensable -- these analyses and comments and sketches you've written -- we've needed someone to make us think in practical terms -- a cool mind, that's what you've been for us -- a cool mind ... and with my inkless pen what have I been able to do until now? I've given money I never earned. My uncle's money, my father's, my mother's!"

Valery was caught by surprise that Chicherin knew about his notes to the addresses in London and Zurich and had read them. He'd been discreet the whole time from San Francisco until this very moment, or thought he had.

"What I wrote was circulated?"

"Of course!"

"And attributed to me?"

Chicherin apparently found it indelicate to say so. "Look, my friend, there's been our fractured revolutionary world, and then there have been a few keen minds that didn't bother with parties and make fools of themselves. Imagine, me a Menshevik! And now I'm a Bolshevik! But no one ever thought you weren't with us. Ever."

Chicherin was innately a kind man who had been kept out of Russia for years, but now he was back and welcomed kindred souls, of whom he counted, quite clearly, Valery Asimov as one.

"You lost Ivan Karamazov," he said. "I don't know how much more one has to give."

Valery took in Chicherin's meaning. Chicherin thought Valery, like himself, was homosexual, and that the notorious Ivan -- to whom something must have happened although no one knew what -- had been his lover. Let it go, Valery told himself. He couldn't waste the man's time to correct his own reputation. With a quick turn, he likened Chicherin's large contributions to the revolutionary effort to Katerina Ivanovna's important, if smaller, financial contributions, but now ...

Chicherin got the point. "You say she gave Vladimir Ilych money for more than twenty years and now she's under house arrest?"

"107,000 rubles," Valery said. "We met him in Berlin when he was still Ulyanov."

They were almost twins -- Valery and Chicherin -- a fact that escaped neither of them: bald, lightly bearded, middle aged, well-dressed, roughly the same height and weight. They could have been puppies from the same litter raised in the same kennel. And in fact they had been; it was called the foreign ministry once upon a time.

"But she hasn't seen him since London, 1903," Valery added.

"What else?"

Valery hesitated. He supposed he'd have to go into it and unglue some of the affinity Chicherin assumed they shared with one another. "She was the lover of Ivan Karamazov, not me."

This annoyed Chicherin, which he attempted to conceal by moaning, "Oh, Dostoevsky. I could never bear that man."

Valery took the same tack with him as he had taken with the taxi driver and said nothing, but Chicherin regrouped and with his quick intelligence pressed hard: "What did happen to Ivan Karamazov?"

"The Okhrana murdered him. It happened in San Francisco."

"Where you there?"

"Yes."

"Oh, my god, did they just get away with it?"

Valery told the truth. "No, they did not. It was one man, and that man has never been seen again. Someone killed him. I'd rather not go into who."

"What about the other Karamazov brothers? Weren't there three? I haven't read the book since I was a boy."

"One died on the fringes of the 1905 war."

"Fighting for Russia?"

"No, no, against. He hated the Czar. And the younger, who is religious, and some children are in California and New York living under a different name. In that sense, the Karamazovs have been erased from the world altogether." He thought this was a judicious thing to say even if he did not like saying it.

Chicherin was a man whose cosmopolitan complexity drove him more deeply into things than time, or what he referred to as "Moscow," a metonym for all of reality, allowed. He wanted to ask about this "different" name; he wanted to think back with Valery as to whether Dostoevsky made it clear Dmitri, the eldest son, did not murder his father; he wanted to be reminded about the bastard son who probably did kill the old man; he wanted to say the problem with novels anyway was all this wealth of interesting but excessive detail. In fact he did say he wanted to discuss these things but gave Valery no opening to do so. He was under too much pressure. He was faced with a decision. The decision was this: whether to put Valery close enough to Lenin to get a word in or say it was frankly impossible and unthinkable and conceivably would be counterproductive.

Speaking so fast while saying he didn't have time to talk, Chicherin made Valery reflect on one of his father's adages: say yes in short letters and no in long ones. For Chicherin was off again, desperate to confide in someone who wasn't part of what was happening. The state was in a shambles. State? How could one even call it that? Everywhere, just as in this place Valery talked about -- this Skotoprigonyevsk -- factions were at one another's throats. Who was the real revolutionary? Who in charge? Should Russia be centralized when that always was its weakness and crime? Or should local control and self-direction prevail? Chaos, it was pure chaos.

"We are being ground up in the maw of a giant threshing machine. So much is chaff, yet we can't worry about that, can we?" Chicherin asked, thinking that by talking long enough he had made clear he couldn't help Valery or anyone else.

In the softest of tones, Valery objected, however. "But I love her, you see, and I don't think she's chaff, and we're back at the same issue Ivan Karamazov focused on first: justice for each one or justice for none. I can't turn the corner that says justice for none leads to justice for all."

Chicherin grinned a grimace-like grin, seeking to soothe Valery. "We'll get there."

"When?"

"Not in our lifetime, perhaps."

"But I have been given three days -- one of which is already used up -- to return to Skotoprigonyevsk with something from Lenin. That's the demand."

"Or ... ?"

Valery didn't want to answer this question. He was angry. How could Chicherin -- having said what he'd just said -- not know people were killing people all over Russia, not in acts of war, but in madness and desperation?

Chicherin understood. Of course he understood. And kind soul that he was, he yielded. "This evening there will be a meeting in the Kremlin. Lenin will be there. Come with me."

Valery walked out into the darkening street with three hours to pass before rejoining Chicherin. Moscow again. Lonely wide boulevards, mansions of Tolstoyan proportions, a chestnut seller catching his eye. When had he last eaten? The chestnut seller was a young woman with freckles who sold him two cones of newspaper filled with chestnuts so hot and difficult to eat that he had to stick first one hand and then another into a snow bank to extract enough cold, ashy snow to cool his mouth. He backed into a doorway and stood there, crunching chestnut after chestnut, grabbing more snow when he couldn't stand the burning in his mouth, watching a cadre of soldiers march past and the street, which had been empty except for the chestnut seller when he arrived, begin to fill up with prowling scavengers and not a few prostitutes.

He didn't have time to go to a hotel and come back, and they must have rooms, mustn't they? He considered this.

A man came along and took over the chestnut seller's fire and pan of oil and nuts, and she walked over to the side of a building a few paces from where Valery stood, lit a cigarette and after a moment or two looked his way.

#

They walked through the Kremlin seemingly forever. At one point Chicherin was lost and laughed about it.

"So I suppose we retrace our steps as best we can," he said.

"To that brown hallway, if I remember it?"

"Yes. And there should be a double door, and we take a short flight of steps to the right. That's where they like to meet."

"They?"

"I mean Lenin and Trotsky. Because Dzerzhinsky has told them it's a safe place where no one else goes."

"Will Dzerzhinsky be present?"

Chicherin's fatigue seemed to have lifted somewhat on the eve of encountering these exalted personages. He patted Valery on the shoulder, a sixth form boy being kind to a fifth form boy. "Our security chief will be and he won't be. He seems to be everywhere even when you're talking to him and can see he's right there in front of you. What and who is Dzerzhinsky? I don't know, which is what Lenin wants. He says there must be terror, and Dzerzhinsky is the one who wears terror's suit."

Something about having met, separated, and then come together again made it feel as though they were old acquaintances. The powers and mysteries of the Kremlin's dreary passageways reinforced this feeling. One could not be here in a czar-less world, history undone like a chair that had sprung all its caning, no one sitting on its bottomless throne, yet one was, and one needed a companion.

"I've been wondering how I could use you," Chicherin said as they walked along. "But not in Madrid. Spain's a feeble place, isn't it? Weak and useless?"

Valery agreed but said that might make it susceptible to a revolution of its own ... at least in Barcelona. He had written a number of notes about the factory committees there and the socialists with their little round eyeglasses and hatred for the Spaniards, seeing themselves as Catalans with outreach committees to the Basques and connections into the French Basques and a cultural affinity for the Provençal as far as he could make out, though the very impenetrability of these people, especially the Basques -- no one yet knew where or how their language originated -- made them unlikely partners.

"Nonetheless, one might be able to do something with the Catalans. You can almost understand them if you speak good Spanish."

"Do you speak good Spanish?"

Chicherin asked this question in good Spanish and Valery answered in good Spanish, and they both clearly wished they could stop and talk a while more about Spain and its unruly regions and potentialities for the socialist cause. But there wasn't time. The clock was ticking.

Chicherin said, "Frankly what I'm thinking is that your time is up there. Perhaps that's what I should say when we go into the meeting -- that I sent for you."

Valery said, "I wonder if that would be a good thing, given the pleading I plan to make."

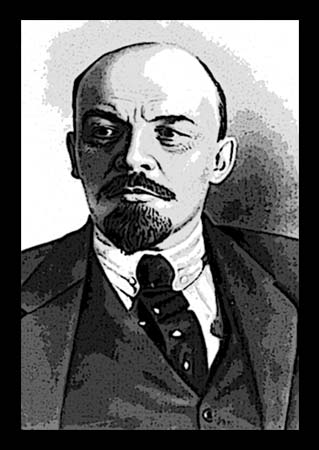

Just as they entered the meeting room on one side, they saw Lenin enter from the other, and Trotsky already in place at the table, leonine and perturbed that he'd been kept waiting, with the cobra-like Dzerzhinsky beside him.

Chicherin whispered to Valery, "My problem is he'll say nyet. Ask whatever you want to ask but he'll say nyet."

Lenin knew Valery and didn't know him. They had both looked somewhat old when they were young, so they didn't look that much different now, but they had not seen one another in twenty years and then only over a ten day period. Both were stockier, Lenin as poorly dressed as before, Valery as well dressed. Lenin looked at him neutrally as he heard Chicherin out -- he had asked Valery to come from Madrid to assist because Valery had spent so many years enlightening them all with his trenchant notes -- but it wasn't long before the Leninesque brain began testing itself.

"You went to London with Karamazov when I didn't want you to, but then made it to America where he was useful until he was killed. After that, you went to the peace talks with Witte and sent us useful things, but all it amounted to was Witte getting out of the Japanese war with the Czar's skin intact. No reparations. Then more from you about San Francisco and New York. Then Mexico and Spain. What can you do with Spain? What if the Spanish were sprung into the war? Aren't there people in Barcelona who would do that? It would destroy their monarchy, do you realize that? One socialist brigade marching up into France confusing things, opening another front." Lenin liked his train of thought. The battlefield of Europe glowed in his eyes. "We need different fronts, political fronts, confusion we can sort out later, national bankruptcies, mutinies, and strikes. Why bring Asimov here when he could work on all that there?" Lenin was talking to Chicherin now, and not pleasantly, as if he were a schoolboy who hadn't done his homework. Chicherin blanched an even whiter white than normal, the white of a fish belly. Lenin sat across from Trotsky and Dzerzhinsky and gestured for Chicherin to sit beside him and Valery to sit beside Chicherin. Dzerzhinsky looked almost Chinese with those high cheekbones and tiny eyes. Trotsky verged on a Jewish prophet, a Jeremiah or Elijah, his hair a kind of storm. Lenin put both arms on the table and leaned forward. "What do you think?" he asked Trotsky. "Wouldn't Spain in collapse help us? Have you ever seen Goya's disasters of war? They're natural murderers there."

Trotsky vied with Chicherin as the most cultured of the Bolshevik leadership, but unlike Chicherin, who had been given culture by his famous uncle, Trotsky had earned his culture under the wing of his decidedly unfamous uncle, a man named Bronstein.

"Natural is an unfortunate adjective to modify murderers," he said softly. "But yes, of course, who hasn't seen them? Los Disastres de la Guerra. If it ever does come to a civil war in Spain, it will be a nightmare, an epic nightmare."

"Then why not?" Lenin asked.

Trotsky had just been pushed out of foreign affairs into military affairs, but this was only days ago; he wasn't comfortable speculating about a brand new war somewhere else and said so. "I think we have more fronts right here in Russia than we can fight and don't need chaos from Chicherin as much as we need money -- loans, bonds, gifts, food. We grow strong by making our friends in the world help us, and they grow strong by making the effort."

"Counterrevolutionaries must be

exterminated. All of them," Lenin said.

The meeting went on this way, a discussion without an agenda, Lenin grasping for ideas ... Trotsky preoccupied with the internal collapse of the empire, the gathering "White" forces, the nationalities restive, Socialist Revolutionaries capitalizing everywhere ... Dzerzhinsky chipping in his clipped, "Da, da, da," ("Yes, yes, yes"), telling Lenin about the gold and silver his agents had seized, fortunes from the vaults of well-known aristocratic families and copper extracted from the plumbing of palaces and mansions ... Chicherin suggesting where these funds and metals could be converted to currencies that would buy guns, uniforms ...

" ... and food, an army needs food!" Trotsky interjected.

"But we can't always say that," Chicherin protested, "because we have made peace and can't let the Germans see us rebuilding our forces."

"I'm not talking about fighting the Germans. I'm talking about fighting ourselves," Trotsky said.

"Counterrevolutionaries must be exterminated. All of them," Lenin said.

"They die," Dzerzhinsky agreed.

"Of course, this is what I am saying," Trotsky said.

On like this. Tea served. Valery realizing that Chicherin, though least involved in the conversation, had an accepted role in this council; otherwise how could he alone have an aide nearby? Stalin wasn't there. Zinoviev, now back in the fold after his exile, wasn't there. What were these four men doing? Was it planning? Was it self-encouragement? They spoke with candor and yet obviously did not trust each other. Lenin said repeatedly that the worse things got, the better.

"And we are making things worse! We excel at it!"

"Da, da, da," Dzerzhinsky concurred before Trotsky made one of his famous speeches, conversationally, it is true, but a speech nonetheless. He must have 500,000 soldiers and he must have trained imperial generals to command them while Dzerzhinsky (he called him "Felix") had to have increased latitude to terminate the tail-less apes of counterrevolution who were too weak-kneed to fight in the White armies but were dangerous nonetheless.

"And Comrade Chicherin, no matter what happens," he continued, "you must tell the world over and over again: Comrade Lenin does not mean what he says. We aren't out to undermine every government in Europe. Oh, no, not so. You are the Commissar of Lies," he said to Chicherin. "Felix is the Flame of Truth, I am the Angel of Death, and you," he said to Lenin, "are the Angel of Life."

In short, Valery thought, Trotsky the Jew had the Book of Revelation in mind, too. He was talking about the End Time. He was talking about the Hegelian antithesis: Conquest, War, Famine and Death leading to socialist Life, all of it masked to appear what it was not.

Lenin smiled his centimeter smile. He was, Valery realized, staging this meeting for Trotsky's benefit so that Trotsky, who had opposed making peace with the Germans, could say such things, though not in front of Stalin, Zinoviev and the others.

"No one who asks receives," Lenin summed things up. "But those who give can keep on giving."

"Da," Dzerzhinsky said.

That seemed to be it. Lenin pushed back from the table. As he did, Valery leaned forward. He'd just heard something that almost seemed designed to be his answer, so much so that Chicherin, who heard it, too, reached over to place a hand on his forearm -- to silence him -- but he couldn't let this opportunity pass.

He said a supporter whom Lenin knew well, Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtsev, who gave everything she had to the Revolution now faced grave consequences at the hands of Left Socialist Revolutionaries and their soviet in Skotoprigonyevsk, and he had been given leave to obtain something, whatever Comrade Lenin deemed appropriate, to establish her bona fides.

Lenin disliked hearing this. Trotsky seemed amused. He tweaked Lenin. "Another source of funds no one knew you had? But did she give so much?" he asked Valery, before turning immediately to Chicherin, "For example, how much did you give?"

Valery objected, "The Commissar is immensely rich. This woman -- "

Lenin was having his meeting spoiled and wouldn't permit it. He said, "Nyet."

Chicherin grasped Valery's arm more tightly, telling him he had his answer. But Valery wouldn't be silenced.

"I must return with something in hand by tomorrow -- anything. I don't say what."

Lenin glanced at Dzerzhinsky. He asked if the Cheka had men in Skotoprigonyevsk. Dzerzhinsky said of course. "Then use them," Lenin said. "Take care of this counterrevolutionary soviet."

In an instant, Valery realized what that would mean. They'd kill Lisa Khokhlakov. "No, that isn't the way. All I need is something from you."

"The Angel of Life," Trotsky smirked.

Lenin's face froze in disgust. He took a pen from its stand and quickly signed his name on a piece of blank paper Then he didn't bother to push it toward Valery, just got up and said as he did, "Put above it whatever you want."

Exactly the man he had been in Berlin. Born that man, forever that man.

Chicherin didn't speak as he and Valery retraced their steps out of the Kremlin. He walked quickly, taking no account of Valery walking beside him. He might have been, Valery thought, as afraid as he was angry, or he might be, as proved to be the case, already done with him. They reached the courtyard where Chicherin's car waited for him -- just for him, not for Valery.

"You can go back to Spain if you want, but only to pack. We don't need you anymore, Asimov. I'm afraid you're not much of a diplomat."

"I got what I wanted, didn't I?" Valery protested.

"Did you?" Chicherin asked.

Chicherin nodded for the door to be closed and his motorcar pulled away. It was past midnight, though the sky was a light gray because it was snowing. Valery walked out into the street and found himself a horse-drawn cab. There was no point in going to a hotel now. He went to the train station instead.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.