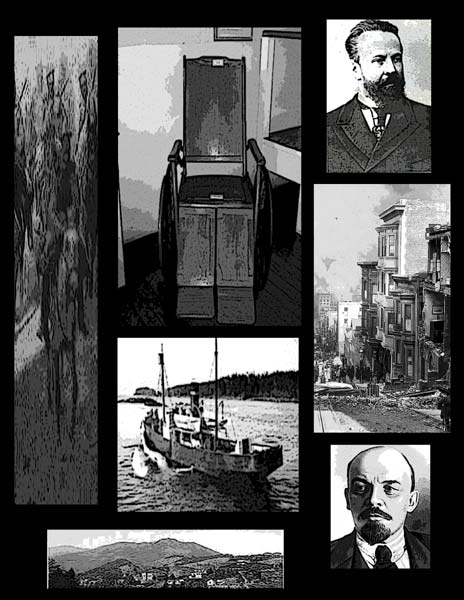

Katerina Ivanovna, bewitched by Valery's tale, rejoices at the czar's defeat. Yes, she and Valery have talked all night, but there is something else she must know: what happened to Christina and her child, Deborah, in the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906? She hears of more death, more destruction, but also the awakenings of a new generation of Karamazovs under their adopted surname, Theodore: Gift of God.

Part II (continued)

He became so enmeshed in telling Katerina Ivanovna these things that he almost forgot he was talking and certainly had no idea what time it was. She hardly cared. She said she felt she had not really spoken to anyone in years. They drank water, he sitting on the bed where Ivan used to sleep, she sitting in the chair where Ivan used to read.

Sometimes she would hear him reading books in English out loud to himself, she said. "Practicing what you taught him, getting ready for your lesson the next day."

"I certainly didn't prepare him to talk like this, the way you and I are talking. But he did. Ivan, you know ... even in English, he was brilliant."

She smiled the way one smiles in the face of irrecoverable time and loved ones lost and the tyranny of memory. She told Valery she reached a point when she knew her capital couldn't restore itself, when she couldn't make up for what she was sending Lenin, her harvests wouldn't do it, her economies wouldn't do it, but she was desperate to find some meaning in her sacrifices, and the whole chaotic period he described -- the massacre at the Winter Palace, the disasters at the hands of the Japanese, the resulting Treaty of Portsmouth -- she mistook as many mistook as the end of Mr. Czar, as she called him somewhat humorously.

"Mr. Czar had to turn things over to your Witte, Count Witte now, and so I thought, 'Ah, this is how it will turn out, and I will have contributed somehow to a better Russia. Lenin won't have foreseen it as such, nor will I, but here it is -- a Duma! Ministers! Bread! Schools!' But Mr. Czar wouldn't have it. Mr. Czar fought back until he got a Duma he liked, which meant pantomimes of progress and justice. Out goes Count Witte. In comes the fierce but obedient Stolypin in his place. New courts. New repression. Summary injustice! Stolypin pushed the peasants onto their own land far out in Siberia, and said it wasn't punishment anymore, it was a privilege -- they'd each have their own piece of ice. I found it unbearable and thought to myself, 'Now we'll never have a revolution, now it's all lost.' And then really, it was unimaginable, only the horror of general war was force enough to end Mr. Czar's tenure. Who would ever think we couldn't do this ourselves? That the world would have to consume us by the millions first? Shoot us and starve us? We're tough, aren't we, we Russians?"

Katerina Ivanovna described it all magnificently. She spoke in bursts that summarized and embodied the currents within herself. Valery always had thought you needed events and personal situations to force you to grow into whatever fullness you might achieve, but she put the lie to this. You could sit in Skotoprigonyevsk and change profoundly all the same. She was great from the inside out. Disciplined. Still proud. And beautiful in the wasted way that age and undernourishment conspire to accentuate one's essential mortal self -- there one is, hot-eyed with the effort to survive.

"So you went back to San Francisco to the woman who wasn't yours and the baby who wasn't yours either," she said. "What then? What happened to Dmitri and the boy?"

#

One day a boy came into the Russian consulate. He said his name was Aaron Theodore and he had something to tell the consul. Mrs. Morgan had an intuition and led him in and stayed in the doorway as if prepared to take him out of the consul's office if necessary but really to hear what he had to say. Valery told Aaron this was all right. He could trust Mrs. Morgan. Mrs. Morgan got them tea and the three of them sat down and Aaron said that he and his Uncle Mitya and the crew had sailed the Tiburon into Port Arthur, taken stock, and transmitted what they'd seen back to Japan on the radio the Japanese gave them. He did this himself as the crew was offloading the food and things the Russians were eager to have.

He could still repeat which ship was where and who was on deck and what was happening -- not much -- and the route they'd taken through the mines. That was clearer to him than anything else. He recognized the voice of the man in the black suit on the other end of the radio. They were speaking in English, except when the man in the black suit, wherever he was sitting, translated what he was hearing to his colleagues in Japanese. Mitya looked in on him several times and smiled at him. "You're your Uncle Ivan's nephew," he told him. "You're doing what Ivan wanted done. And what I want done. I want these Russian ships down. Send them to their grave!"

Aaron was not the same boy who had sailed to Asia. He was taller, sunburned and gaunt. He spoke with certainty and clarity. He said he hadn't been to Strawberry Point. He'd come straight to the consulate. Valery asked how he got from Asia back to California.

What had happened was this: he was almost finished saying things and answering questions on the radio when Dmitri told him to stop; he'd said enough; he was just to tell the man in the black suit to give them an hour to get clear of the harbor. But there wasn't an hour. They backed away from the dock, raised their jibs, and torpedoes came whitening the water right past them. Dmitri cried for them to push! Push! They had to get out. They powered as much as they could and raised the main sail while behind them, and eventually all around them, there were huge explosions and suddenly -- it was almost dark -- counter fire from Russian guns bursting above their heads and the Tiburon was hit, but Aaron didn't know which side hit it. He was flung off the ship and didn't know he was alive until he found himself choking and struggling to keep his head above the water.

Mrs. Morgan was white as a sheet of paper. Valery fought to remain calm. He could not tell if anything Aaron described meant anything to him -- if he felt it! The rest of the crew was lost. Aaron never saw any of them again -- Dmitri, Markus, Ilya, Raphael, or Vlad. A piece of torn planking hit him in the head and cut him (he turned his head and used his fingers to pull back his shaggy hair and show the scar) and he realized he'd better grab it. Then he started kicking, trying to get out of the way of the attacking Japanese war ships.

"Weren't you afraid?" Mrs. Morgan asked.

"No, ma'am. Not anymore."

He found a shoal and scrabbled along it. The night sky blossomed with fiery bruises. He knew how the land would be if he could get to it. There would be Korea, then the Sea of Japan, then Japan, then the Pacific. He had all the maps in his head. He'd sat for hours with his uncle studying them. He knew them all. So there was a lot of walking ahead of him and Koreans who fed him and a Japanese trader who took him to Hidate and another captain who did the same kind of things that Captain Connors and Dmitri had done and he knew about Dmitri and brought him home, but after this, he couldn't tell his father what he'd done. His father hated war. He would never forgive him or Dmitri either.

"But you have to tell your father," Valery said. "He must know. You're his son. Dmitri was his last brother."

Aaron Theodore, once upon a time Karamazov, couldn't have become who he was if not for what had happened to him, but he was hard, and Valery sensed he was quick, that he would slip away like a fish if spooked.

"Would you live with me until we sort things out?" Valery asked

Aaron said he would.

"And not skip away without telling me?" Valery added.

"I don't want to go nowhere right now," Aaron said.

"What about school?"

"I know how to read and write."

"Clothes?"

Aaron pointed down to the way he was dressed, all whitened denim and rope sandals. "This is it, what I've got on me."

"Some kind of a job?"

"Not milking cows!"

They agreed that Valery would take him to a clothing store and buy him some clothes and then go to Valery's apartment and then to Tina's for supper with Mrs. Morgan and the baby.

They lived this way for several months. Count Ambassador Rosen again asked Valery if he didn't want to go to New York. Again Valery said no. He had his routine, had succeeded in persuading Aaron to attend a middle school, and Tina and Mrs. Morgan and the baby, Deborah, all fell in love with Aaron. The only subject that disrupted things was going across the bay to Strawberry Point, where his mother and father had no idea if he was alive or dead. Aaron refused. He was convinced his father would turn away from him, literally and forever. So Valery went. He had not been to the small dairy farm since the day Ivan was murdered and buried. He trudged through the dust, thought about the whole world as ashes, but could not resist the astonishing beauty of the place with its soft meadows, glistening trees, and golden mountain overlooking it all. And there they were, the infant now on her feet, little Daniela spotting him first, Grushenka at work in the kitchen and Alexei out in the barn, loading milk cans on the horse cart he used to take them over to the Lyford farm where everyone with cows sent their product for transport over to San Francisco.

After Valery had told them the story, and not just Mitya and Aaron's but also Tina's and Deborah's, Alexei pulled Grushenka's face to his shoulder where she cried about her Aaron and her Mitya, and Valery thought whatever he had come to do, he had done. But Alexei said no. If Aaron wouldn't come to the farm, then let Valery keep him.

"You're his father now if he needs one. He's a man, anyway. He's been to war, and wants no Lord, which is all I have to offer."

"But I want to see him!" Grushenka wailed.

"He doesn't want to see you," Alexei told her.

"And Mitya!"

"Mitya's gone."

"Is he? Is he for sure? How can we know? Aaron's back, why not Mitya?"

The little girl, Daniela, didn't believe any of this. She played with two boy dolls, one named Aaron, the other Uncle Mitya. They marched around the floor and talked to one another and seemed to stop at times and talk to her in a special kind of language no one else could understand.

Valery protested, "In all honesty, I am no good with families."

"Then tell him if he wants us, we are here, and we do not judge," Alexei said.

"She'd like to see him," Grushenka said, pointing to Daniela on the floor.

Daniela pretended not to hear.

#

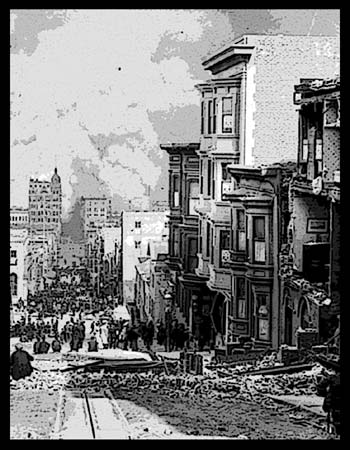

Valery did not want to go on but Katerina Ivanovna correctly sensed there was more and urged him to continue. He took a sip of water and told her that on April 18, 1906, twelve years ago, there was a terrible earthquake in San Francisco but even more terrible were the ensuing fires.

If ever there were an apocalypse, it seemed to him, the rocking, roaring earth and collapse of buildings everywhere and sudden spurts of flames pouring out of gas mains that ignited entire streets and swept up and down hillsides and sent seared human beings into asphyxiating clouds of smoke, surely this was it. He and Aaron were thrown out of their beds at just past five in the morning. Their building seemed to stand despite itself. The elevator shaft crumpled; the stairwell filled with dust and debris. Valery grabbed Aaron by the back of his shirt to keep him close. They were both bruised and cut and half-senseless, but obviously they had to get to Tina's house despite the streets not being where the streets had been and the houses almost melting in the flames and the sun impotent above the billowing ash and the roar -- horses, people ... even wood crying out as though it were animal in nature, too.

Tina's gray house was down the hill from where it had once stood and collapsed into a kind of ragged flatness and encircled by flames. Valery and Aaron scrambled over its jagged mass until they reached what would have been the third floor. There was the baby in her mother's arms although Tina's chest had been crushed by a beam. She was dead, unmistakably and horribly dead. Valery clutched at her and talked to her and begged her to come back, but she was gone. Aaron picked up the child who was still alive. Valery thought he heard Mrs. Morgan's voice in the rubble. He scrambled through the rubble to try to find her, and he did find her, but by the time he reached her, she, too, was dead.

"And it got worse, Katerina Ivanovna," Valery said. "The whole city seemed to keep exploding."

"Like our world here?"

"In one terrible short span, yes." He paused to contain himself. "The fires raged and we did what everyone still alive did -- we ran as best we could to the water, and when we got there, we got on a boat, the whole bay was filling up with overloaded boats, and behind us, black under the sunrise, San Francisco looked like Rome must have looked or London when it burned once, and it would burn for days."

They made it to Strawberry Point where almost nothing was affected or changed. Grushenka took the infant and wouldn't let her go. Alexei told Aaron he was free and forgiven. Aaron said he still wanted to stay with Valery, and Valery agreed. He contacted Rosen in Washington and asked to be reassigned to New York. After that he was minister in Mexico. Then he was Russia's minister in Colombia, and after that, ambassador to Spain.

"What about Aaron?" Katerina Ivanovna asked. "What happened to him?"

"He stayed in New York. I sent him to college. He's a lawyer now."

"And the people of Strawberry Point?"

"They're still there."

With no more to tell, Valery lay back on Ivan's bed and closed his eyes. He was exhausted, asleep so quickly that he did not hear Katerina Ivanovna get up, put out the light, and close the door.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.