On the wrong side of the local revolution, Katerina Ivanovna's long-time support for Lenin and the Bolsheviks does not save her from detention and impending trial before the mob. Lisa Khokhlakov shows little mercy. Valery is given three days to travel to Moscow to see Lenin and plead for his support in insisting Katerina Ivanovna be freed.

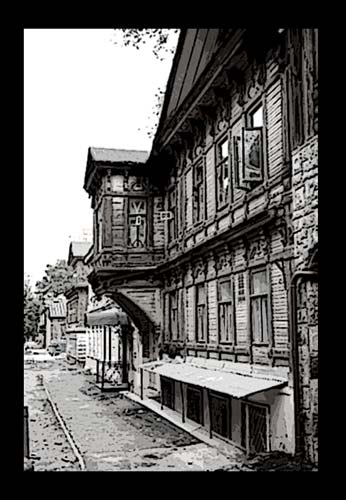

"... the buildings -- how long and haggard

and thin they looked, how marked by disrepair and neglect..."

Part III

How cruel the daylight! The streets of Skotoprigonyevsk were thinly populated with listless folk whose obvious hunger matched what Chekhov had written about Sakhalin, people whose deep-set eyes and pallor echoed Katerina Ivanovna's. What were they all doing? The same thing, searching for food ... condemned to the servitude of hunger ... punished by it ... humiliated by it. Was this the revolution? Old and young, men and women, boys and girls, animals, all of existence gaunt, watchful, and wary? Likewise, if Valery could believe his eyes, the buildings -- how long and haggard and thin they looked, how marked by disrepair and neglect. Street after street struck him this way. He walked Katerina Ivanovna along, their arms linked. She wasn't steady in her gait.

"There will be food at the inn, I promise you," he had said.

She smiled at him with that craziness deprivation brought on. "I wonder if that's so, and if there were, why would we get it?"

He had prepared himself for this journey with silver pesetas from Spain, pound sterling notes from England, French francs, and a few old gold Dutch guilders. And he had Russian rubles in extraordinary dominations, too, but he knew he must find a way to elude needless arguments with her. She would belittle him, shrink him to the circumstances she knew to be true, not what a traveler might expect.

"Come, you'll see," he said.

"Oh, we could just sit a while and talk."

"I feel I should reappear. My things are there."

"Perhaps Lisa Khokhlakov and her allies will be there, too."

"It's too early. Come along, now. Please."

No one appeared to be doing anything resembling work. The shops that were open weren't shops anymore. A butcher stood in his doorway with no meat in his cooling box or ham hanging from his rafters. A baker presided over a similar vacuity. Silence prevailed. No hammering, clattering and rattling, no calling back and forth. He did see a little circle of people who appeared engaged in some exchange that might have to do with packets of foodstuff; someone might have brought a rabbit or a partridge into town or some twisted-up carrots. Of course there was food; there had to be, he told himself. Katerina Ivanovna's bare cupboards might have misled him into thinking that her proud isolation was the common case. That might not be so. She might be an internal exile, shunned. In the harsh, bleaching daylight she looked wan, a likely candidate for ostracism, a well-dressed person whose servants had gone into the countryside where things like game and berries and roots were to be had, if not by her, or any other dispossessed landowner.

They found the innkeeper in the tavern room sitting on his stool smoking his clay pipe. He had placed a few tables and chairs back where they belonged, but they were empty.

"No customers," he said. He was a black-haired man with shaggy eyebrows and a mordant glint in his eye.

"Ah, but no, you have two, Madam Verkhovtsev and myself."

He contemplated Katerina Ivanovna a moment. "Shall it be quail eggs and some smoked sturgeon?" he asked her.

Katerina Ivanovna rebuffed the prickliness in his tone with deft humor. "Only if there is also pumpernickel. I must have pumpernickel when I eat quail eggs."

Valery was amazed. She was flirting with the man.

"Then it can't be the quail eggs because pumpernickel isn't what I've got on offer. What I've got is crumbled bacon soda bread. Will you have some?" he asked Valery, dismissing Katerina Ivanovna's overture.

Valery said yes. The innkeeper pounded on his bar two times. A girl about ten crawled out from down below, where apparently she slept, and padded toward the kitchen.

"She'll fetch you each a slice. What about kvass since there's no tea or milk?"

"You have kvass?" Katerina asked.

"Since dawn I do. By noon it'll be gone."

"Yes, yes," Valery said. "Two glasses, please."

He pulled out a chair for Katerina Ivanovna to take a seat at the table along the street windows. The little girl padded back with two large slices of hard soda bread speckled with bacon and next brought the kvass. She then disappeared once again behind the bar, somewhere near the innkeeper's feet.

Valery decided to speak in German to shut the innkeeper out of things. Katerina Ivanovna regarded this linguistic gesture with the same sardonic, wry displeasure that she addressed to the awful bread, which was difficult to eat.

He said the word in German for masticate was kauen and thought perhaps it derived from the German word for cow, kuh.

"As in 'Die kühe kauen'?" Katerina Ivanovna asked, exaggerating her chewing in imitation of the large sliding jaw of a cow.

Again, that mix of humor and despair.

"More or less." He sipped the kvass, which was flavored with mint. "Akzeptabel," he commented on it, still in German.

"Acceptable," Katerina Ivanovna agreed, going him one better by saying this in English because it was easy to do. Apparently she remembered it from Ivan's English lessons.

Acceptable was an important word in English, Valery commented, implying not the highest standards but higher than one might think: that which was acceptable was actually more than acceptable.

They looked at one another, disjointed and dejected, Valery wondering what the devil he was doing at the moment and then realized exactly what he was doing. He was trying to make her a traveler. He'd gotten her out of her house and taken her to an inn and begun speaking to her in a foreign language and was psychically expressing his conviction that he'd come here to rescue her ... to take her away ... to enable her to escape from Skotoprigonyevsk as Mitya and Alexei and Grushenka had escaped from Sakhalin. She was dying here, and as they kept masticating the soda bread and sipping the kvass, he wanted to say to her that he'd go upstairs, get his bags, and arrange for them to go directly to the train station and then up through the Baltic region and wherever she liked after that. She needn't and shouldn't pack. She needn't and shouldn't go back to the yellow stucco house. Just leave it, pretend it never existed, come with him now ... the clock -- that clock inside! -- was ticking.

But he didn't say that. He knew all she really wanted to talk about was what he had told her of Ivan and the woman he had married ... and the child saved from the earthquake and inferno.

"All I have is this." He reached into his pocket, removed his billfold, and pulled out a photograph of a girl in a white dress sitting against a kind of drapery, looking quite serious but otherwise as unlike Ivan Karamazov as every other child who had ever been born and reached the age of nine months.

He realized Katerina Ivanovna was going to be an old woman soon, perhaps very soon, and wondered if the ticking meant that it would occur right then, right there, as she stared at the photograph of the child of the man she really loved.

She caught at her breath a few times and got herself under control by pulling her hand away from his and covering her eyes with it.

Two men came into the inn and took up places at the bar.

The innkeeper said, "What I have is kvass. What do you have?"

One of the men said, "Whatever we want to have."

"Oh, the devil," the innkeeper said.

"The devil's on leave; we've taken his place," the other man said. "Now be good about it and pour the kvass."

The innkeeper produced glasses that were smaller than the glasses he'd given Katerina Ivanovna and Valery. The first man turned and said of them, "Who would they be, receiving more than their share?"

"Paying customers," the innkeeper said.

"Really?" the second man said.

Valery put away the photograph, choosing to ignore this interruption. Katerina Ivanovna kept struggling to gather herself. They were now five adults in the large, empty tavern room, and the girl, of course, hidden under the bar. Then some others arrived, making the total eight ... then a few more. Katerina Ivanovna asked whether Valery thought the child could ever have any conception of where her father had come from and who he had been. She meant, Valery inferred, whether the child could have any conception of her, but before he could find some way of saying no, the child couldn't possibly conceive of anyone who emerged from an unknowable, unrecognizable, ruined Russia, he heard the sound of Lisa Khokhlakov entering the inn, the hard rubber of her wheels drumming on the bare oak floors and then rattling as she crossed a sort of threshold of bricks that demarcated the tavern room from the reception area. A handful of men and three or four women trailed after her. She rolled to the table by the window where Valery and Katerina Ivanovna sat.

"It's been so long, Lisa," Katerina Ivanovna said.

"Years," Lisa Khokhlakov said.

Valery studied the two of them, Katerina Ivanovna now a kind of purling waterfall, her face and figure echoing the glinting tears on her cheeks, and Lisa Khokhlakov, twisted and crooked in her wheelchair, almost a receiving pool, capturing the existence draining from Katerina Ivanovna's face and transforming it into that dangerous swirl of spring water and lye.

"She insists on staying in her house," Lisa said to Valery about Katerina Ivanovna. "We wished she'd get the message and give it up."

"Who do you mean, 'we'?" Katerina Ivanovna asked, rebuffing this criticism.

"The whole town," Lisa said, smiling unpleasantly.

"Not only your soviet?"

"It isn't my soviet. No one owns anything in Russia. I told you that yesterday, didn't I?" Lisa said to Valery. "But she's said there's something about her that entitles her, and we have not yet determined what that could be. It's under consideration." She continued looking at Valery. "Why are you still here? Why haven't you left and taken her with you?"

Valery was aware that more than a dozen people were listening. He had the sense that they were a kind of jury, including the two men who had entered the tavern first.

"That's under consideration, too," he said as mildly as he could.

Lisa wheeled over to the little platform and waited to be hoisted her up onto her perch. Then she manipulated the wheels so that her chair spun her back from facing the wall to facing the tavern, into which more people were drifting, the same motley mob as the day before minus the monks.

She extracted her notebook from beside her right thigh and put her writing board in place. One might have thought that next she would call the gathering to order, but she didn't. She uncapped her bottle of ink and dipped her nib in it. At the same time, the innkeeper was removing the glasses of kvass from the bar, though the first two men hadn't finished, and the little girl, her hair black and skin quite white, was slipping over to Valery and Katerina Ivanovna to take away their glasses and the remaining crusts of soda bread with bacon crumbled in it.

"We ought to leave," he whispered to Katerina Ivanovna.

"I don't want to leave," she whispered back.

A woman in a dirty white wool beret spoke as if visited by divine inspiration. "This fine lady," she said, meaning Katerina Ivanovna, "insults us with what she is."

A murmur snaked around the room.

The woman in the beret continued: "We make no peace with you. That isn't our work. Go! Why don't you go?"

Lisa Khokhlakov now asked Katerina Ivanovna from her judging perch, "What do you have to say in your defense?"

Katerina Ivanovna said, "I have nothing to defend."

"What?" Lisa Khokhlakov asked, as if she were hard of hearing. She held up her pen waiting for an answer so she could write it down.

Valery couldn't restrain himself. He spoke to the woman in the white beret. "She means that her material possessions are in other hands. I am referring to what were her lands. And she gave what money she had to Lenin so that this new order could come into being."

In a very clerical way, again with pen poised, Lisa Khokhlakov asked, "Is there a record of this?"

"We don't keep records of such things, of course not."

"We?" Lisa asked. "Who are 'we' when you say that?"

"She gave money. I sent reports to Lenin and I never kept a record. either. It was too dangerous."

"But that's not true exactly," Katerina Ivanovna said. "Here, my ... " She extracted her little blue leather book and gave it to Valery, the book with the dates, the numbers, and the locations.

He wished she hadn't done this, sensing that any formal defense would be offensive to this mob, because it was by now a mob, forty or more people gathered together, several of whom had squeezed in behind the bar to see if there was anything there to eat or drink. So much for the flask of kvass.

"Give that to me," Lisa Khokhlakov said.

Unwilling to let others pass the little blue leather notebook to Lisa Khokhlakov, Valery took it to her himself. She studied its pages, made some calculations, and announced, "This woman was rich, 107,000 rubles! Whose rubles were they? How did you get them? Someone earned them, didn't they? But they fell into your hands, and you say you sent them to Lenin while we here had nothing? I gave all my rubles to people right here, didn't I?" she asked, looking from face to face. She kept on: "And what did Mr. Lenin do with them? And who gave him that right? And who is he to this soviet, now in his Kremlin sending them -- " she pointed at the two men standing at the bar who had entered the tavern first, obviously representatives of the new secret police " -- to spy on us? Are you in league? What are you doing here?" she asked Valery directly. "You sold all your uncle's properties and off you went, rich! Do you come back with them now -- " again she meant the two men at the bar " -- to organize our demise?"

She stopped, pen in the air, wanting answers so that she could write them down, giving Valery to think, just by her schoolmistressy way, that perhaps her notebook wasn't a doomsday book, an unfolding Inferno into which he, Katerina Ivanovna and the men at the bar would descend ... perhaps all she wanted was a record ... naïve as it seemed to think such a thing.

"I do not know these men," he said. "I know Madam Verkhovtsev and have come to see her. Lenin will have to answer for his part as to what he did with the funds she gave him, or perhaps he already has. He's where he is, and we're here, and the Czar and his ministers have been dispatched."

"And there is no peace, no land, no bread!" someone cried out.

"What do you say to that?" someone else asked.

"There was bread there!" a third person said, pointing at the crumbs on the table where Valery and Katerina Ivanovna sat.

"What we should do," the woman in the dirty white beret said, "is take her house as we have taken her lands. We know where you live," she scolded Katerina Ivanovna. "Pyotr and Marfa have left you, haven't they? Weren't worth the trouble, were you? It's all lies. People like you should die for your lies."

"There's no need to talk of anyone dying," Valery said. "Peace, wasn't that the first word? Peace, let's have peace."

"My arse," someone said.

"Would you fight for it? You?" someone else called.

Valery couldn't answer them all, argue with them all, and knew he shouldn't. He turned to Lisa Khokhlakov who pondered him as if amused by his dilemma.

"We hear nothing from your Lenin and don't expect to," she said, "but this woman will be detained for three days in her home before her sentencing to give you time to pry loose from him what he offers us if he offers anything at all."

She then looked down at her notebook and began writing in it as several men surrounded Katerina Ivanovna and physically picked her up, just as they were accustomed to picking Lisa Khokhlakov up in her wheelchair, and carried her through the jeering crowd out of the room.

#

The two men were from the Cheka. They were upon Valery almost as quickly as the mob fell on Katerina Ivanovna, and they pushed him down the corridor to the kitchen, where they found the frightened little girl sitting on the table. Seeing them, she ran out the back door.

"Who do you think you are, using Lenin's name as though you know him?" the first Cheka man said.

"I do know him," Valery said.

"The devil," the second Cheka man said, bracing himself against the kitchen door so that some of the crowd in the tavern who had followed them couldn't get in. "Follow that little girl."

Quickly they went out the back door, just in time to see the little girl shutting the gate through which she fled. Out in the alley, she screamed, "Don't hurt me!" The Cheka men had Valery by the shoulders and were half dragging him along. He had never been strong when he was young, and he could almost be called old now. They came to a warren of muddy lanes and shacks and stables and slipped into a rusting factory compound.

"It ain't your business to be saying Lenin this and Lenin that," the first Cheka man said, pushing at Valery with the butt of his hand.

"We'll take care of what's going on here," the second Cheka man said. "You leave that to us."

The innkeeper found them. "Where's my little girl? What have you done with her?"

"We've done nothing with her," the first Cheka man said.

"Now get out of here," the second Cheka man said.

"And him, what will you do with him?" the innkeeper pressed.

"Him? What about you?" the second Cheka man said, lowering his shoulder into the innkeeper's chest and knocking him into the dirt.

The innkeeper scrambled onto his hands and knees. Before he could speak, the little girl streaked through the factory gate and threw her arms around his neck.

"Leave my daddy alone!"

"We've got no interest in your daddy, now git!" the first Cheka man said, letting Valery go and kicking at the girl, his boot glancing off her rump.

Valery cried, "Enough! Gentlemen, listen to me. Take me to Moscow, and I'll speak with Lenin."

Both Cheka men looked at him with surly suspicion. "You don't understand, do you?" the first said. "This is a town on our list. We're here now, and we'll settle it. We'll move forward, not back. Comrade Lenin's got nothing to do with it."

"Then who do you work for?"

"We work for no one with a name, and if we knew it we wouldn't tell you," the first Cheka man said.

"Then what is your name?" Valery asked, his composure his only tool and weapon. "Mine is Valery Asimov."

The first Cheka man said, "Konrad, just Konrad."

The second Cheka man said, "Alexandr."

"Thank you. One wants to know, of course." Valery pulled his coat in order. He took a few steps forward and helped the innkeeper get up, putting his handkerchief on a purple knob that had formed on the poor man's temple. Then he kneeled to calm the little girl, who said her name was Anna, and her Daddy's name was Viktor, and she had no mommy. The more deliberately and methodically he moved and spoke, he knew, the better his chance that he could save them all. That's how he put it to Konrad and Alexandr.

"Right now you're known, and you need to leave and report to your superiors and take me with you." Then he said Viktor and Anna. "Could you take a message to Madam Verkhovtsev? Could you say I have gone to see the man called River?"

"Man called River?" Viktor asked. "What River?"

Valery didn't answer. He simply repeated his request, directing it equally to Anna and Viktor because he didn't know which of them, really, would be the ones to reach Katerina Ivanovna with his message.

"Now Konrad and Alexandr," he said, "I have done many things in my life and am part of why you are here. You may not have realized that, but take note and believe me: either we leave or we're lost. I only have three days to return. You heard that. Let's go."

"No, we've been told to stay," Konrad said. "We won't be alone here long, I will tell you that."

"Both of you? You both must stay?" Valery asked.

"He's my partner, I'm his," Alexandr said. "We don't budge or I'm killing him for leaving and he's killing me."

"Don't kill anybody!" Anna cried, putting her hands over her ears.

"Too late for that," Alexandr chided her.

"Then I'll leave alone," Valery said. "You'll see me walk out that gate and I'll walk to the train station, and I will go to Moscow, and I will see whom I said I was going to see and return. Tell her," he repeated to Viktor and Anna. "The man called River. And remind Madam Khokhlakov she gave me three days. You'll see her, won't you?"

"Oh, we'll see her," Viktor said. "That inn of mine's hers, or haven't you understood that? What about your things?"

"I don't need my things. I'll be back soon. I promise you."

Valery smiled a smile he might have offered after a meal at a men's club. He then shook each man's hand, bent down and kissed Anna on the top of the head, and walked away with complete composure and self-possession, wondering whether he would be shot in the back. But he wasn't. He made it all the way to the train station, and when the train came, he bribed his way into a seat, from which he watched the endless pines, pines after pines, flicker and quiver, no bird life in there, no deer, everything in the soft dark gloom along the tracks in hiding, as it were, alarmed by the fearful passage of this steaming chugging beast.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.