At the end of episode two, Katerina Ivanovna cried to Valery Asimov,"You've got to tell me what happened." She meant he had to tell her everything about Ivan Karamazov's death, what happened to his brothers Dmitri and Alexei, and the unborn child Ivan left behind in Christina McGrath's womb. In this episode, Valery's memories of that child's birth back in 1905 take center stage. Christina, after all, is a widow, and now that Ivan is dead, someone must take care of her.

Part II (continued)

Valery started where he thought he should if there was an ounce of justice left anywhere, and there she was. Christina had two suitcases out, but they were only half packed.

"Where would I go?" she asked by way of explaining why she had stopped and simply gone into the parlor and slept on the couch in the same blood-spattered clothes she had been wearing the day before.

He placed two bottles on the table. Milk. Alexei had insisted he take them along.

"Is it pasteurized?" she asked.

"I wouldn't think so."

"Then I can't drink it. I'm pregnant." She said this as though he didn't know or couldn't guess just by looking at her. "I'm going to have the baby."

"Of course." He sat down in the gray fabric chair across from where she lay. "My God, I am so glad to find you here," he said, speaking more honestly and earnestly to her than he ever had before.

She ignored his feelings. "That man took me to McGrath. McGrath paid him, and the man asked me to go to Ohio with him, and I walked here. I have no money."

"I have money."

"That's right, you're rich." She didn't say this to flatter him. She said it indifferently. "I don't know why I even mentioned money. I meant I didn't have money for a cab. McGrath's man killed them both, but the first one to attack Ivan was Russian. That's what McGrath's man said."

Valery nodded. "Yes, it was the Russian who attacked first."

"Who are you people?" she asked, referring to all Russians everywhere.

He gave her a divided answer. "We are people trying to destroy an empire while the empire is trying to destroy us."

"So that's why this Russian came to kill him?"

"McGrath's man was the one who actually killed him," he reminded her.

"Only because he wanted them both dead and all of McGrath's money for himself."

"McGrath's money is empire money, too," he said.

"What money isn't empire money?"

"None of it, I suppose."

He didn't see the point in talking money and politics with her. He said that Alexei and Grushenka would like her to live with them on their farm, or if not, she would be welcome in one of his spare bedrooms for as long as she liked.

"I'll stay here, thank you," she said. "So actually what you're saying, and it's true, is that if McGrath's money was behind it, American money -- American lead, silver and gold money -- I'm the one who made him die."

"I'm not saying that at all."

"You won't ever convince me of that." She was angry and wanted to provoke him. "Is he buried?"

"Yes."

"I won't ever go back to that farm."

"All right."

"The whole family, I don't want to see them. I don't want my baby to see them."

"I can understand that."

This infuriated her. "What can you understand?"

"Your wishes."

"They're not my wishes. It's how it will be. Understand that!"

Valery nodded, almost bowed. He didn't want her to hate him but could easily understand that she might, although by the same token he knew she needed him, too, and must realize that. The two bottles of milk gave him an idea.

"If I went out and bought you pasteurized milk, would you drink it?"

His kindness embarrassed her, but she was famished. "There's a store at the corner. Dump the milk in the kitchen sink, rinse out the bottles and you can buy pasteurized milk there. And rolls and butter."

"What about jam?"

"Yes, jam, and ... ."

"And what?"

"Well, bananas."

He went to the store and returned to find her sound asleep on top of the bed now, still fully clothed, the half-packed luggage on the floor. He put things in the kitchen and then softly went back into the bedroom, startled to realize she was wearing one of Ivan's pearl gray vests, beneath which protruded her swollen belly. Wake her? No. He walked to the consulate where Mrs. Morgan demanded to know where he had been.

"Look at you!" she exclaimed.

He looked down at his rumpled clothing and the dirt on his shoes and trousers. Straight off she pulled a clothes brush from one of her desk drawers and began putting him in order. It wasn't clear she wanted to be told what had happened, but he had to say something because he needed something from her, something important and unusual. So he said that a Russian man had become involved with a young American woman and now the Russian man couldn't be found and the American woman assumed that he was dead.

"Dead!" Mrs. Morgan cried, knowing this was true, fearing that Valery had confirmed or even witnessed it. "Oh, my God, these Russians!" she exclaimed. "I'm sorry but ... "

"No need to apologize," he assured her, "but the woman is alone and ... "

"You want me to go sit with her?"

"Yes."

"Why of course I will. Do I need to pack for overnight?"

He said the baby wouldn't come for three or four months.

"Will the baby be yours, Valery?" she asked.

"No, it's not my baby. But I did know the man. I knew him well."

Mrs. Morgan moved in with the woman she knew as Tina Theodore, which is what Valery insisted on. In the mornings Mrs. Morgan would get Tina "going;" midday she went to the consulate. By late afternoon she was back with Tina, helping her prepare clothing and furnish a baby's room and arranging for a visit to a doctor and contacting a midwife. Then there was supper to prepare, which Valery usually attended, glad to see that the women liked one another, their maternal instincts alive and intermingled, sometimes Tina the child, sometimes the being in her abdomen playing that role, hearing fragments of song -- "Old Man River," "Amazing Grace," "How Bright Thy Light Shall Shine" -- that Mrs. Morgan hummed and sang in an agreeable alto voice.

During his days, he realized how reliant he had been upon Ivan and how impotent he felt in carrying out their subversive mission alone. Ivan had a sharper wit and greater perseverance, was less cautious than Valery, and possessed a finer eye for targets of attack. Now the city read in its newspapers no monologues about what it was like to be whipped or extended fables about the Russian bear who persisted in consuming Muslims although Muslims gave it flatulence or the legendary czar who wanted to live as a peasant for a week and when he returned to his palace was beheaded by the new peasant king who didn't want to give his palace back to him -- imagine his surprise! John Patmos the prophet had entered his own end time, and there sat Valery Asimov, dwarfed by the immensity of whatever lay beyond his consular duties. He missed Ivan as his friend, and he missed Ivan as one of the world's few chances to get things right.

He wrote to Katerina Ivanovna employing the diplomatic formula of sorrow and sympathy, never mentioning, for the sake of eluding the censors, the name of the beloved friend she had lost or his manner of death. He simply didn't think he dared risk the full truth in lemon juice ink. She would know what he meant when he encouraged her to carry on in honor of the departed's efforts

Would he ever see her again? He doubted it. He thought everything about the three of them had been a kind of fantasy, each using the other to escape a confused moment of romantic passion. He would never return to Skotoprigonyevsk nor would Skotoprigonyevsk come to him. She didn't care that much about him anyway. The man she loved was Ivan Karamazov, not Valery Asimov.

There was an inquiry about Smedlov. Valery answered by saying he'd seen Smedlov once and never again. In any case, there were no more anti-Russian articles in the San Francisco press, so he assumed Smedlov had done whatever he'd set out to do and gone home.

Then he received a message through Ambassador Count Cassini from Ambassador Stoltz in London, who maintained an interest in the case because Smedlov remained "his" Okhrana agent and had only gone to America on "loan." Stoltz wanted Valery to check the morgues. Valery replied that he visited the morgues every Monday and knew what Smedlov looked like and had never seen him there.

In fact, the morgues -- there were two main ones for foreign riffraff -- were like poems to him. Among the fields and shelves of dead, there always was a fallen Russian or two, identified by papers or jewelry or Cyrillic tattoos. None of these were important in contrast to Ivan and even Smedlov dismembered, but each conveyed passages of worn truth in their defeated lineaments. After Ivan's murder, Valery used these bodies as reminders about the completeness and silence of death that ceremonies and graveyards concealed. There, in the morgues of San Francisco, he decided he'd keep on doing things that were similar to what he had done with Ivan. He'd tarnish the Czar if he could and thwart his empire. To the degree a Russian consul could be Nicholas Romanov's enemy, that's what Valery would be.

Katerina Ivanovna replied with a formal note of gratitude for his own note, pledging that her bereavement would not deter her mission in life. She signed the note with her entire name. Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtsev. He read the note's single sentence, smelled the card and then lit a candle to see if there was more in lemon juice. No. No more. Did this mean that what she had written to Ivan all those years, she would never, out of prudence or indifference or pain, write to him? He assumed that it did.

At the kitchen table over supper at night, he listened to the women talk about the baby growing in Tina, babies they had known, and babies in general. The things he might have had to say would be of no interest to them, but now and then Tina smiled at him, and he realized that simply by being there, creating an event with his arrival and departure, being a man who paid the bills and had sent her Mrs. Morgan, he was having some kind of effect on her. One night she asked if he would be the baby's godfather.

He wanted to say that he would promise to always look after them both. He wanted, if it were possible, to take Ivan's place in her life, but she wasn't putting the question that way. So he limited his reply to her question: Yes, by all means. Nothing would honor him more greatly.

Then she said, really dashing him down, "And Mrs. Morgan has agreed to be its godmother, isn't that wonderful? No matter what happens to me, the baby will always be safe."

He wanted to ask her why she wouldn't always be safe, too, but of course, what could she, of all people, consider safe? She'd never feel safe until old Mr. McGrath was dead and Russia was dead, too.

"We need a monkey in the rigging or the hold -- he'll be the squirmer," Markus agreed.

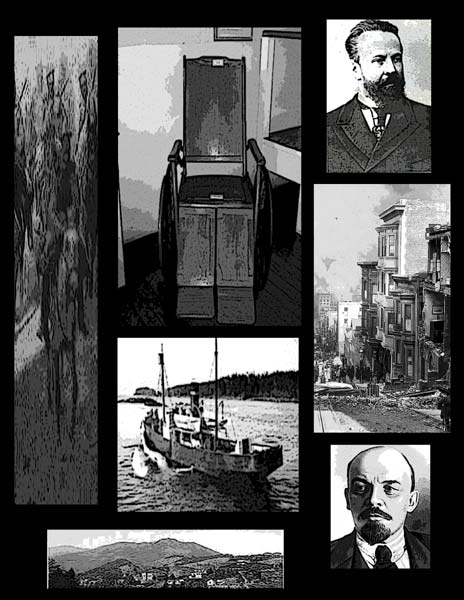

Dmitri led Valery aside. "Alaska, then Japan. Then I'll sneak in along the China coast and find my runaways and deserters and everything I see will go in here," he tapped his head, "and I'll give the Japs what I know and bring the results to you." When Valery told him not to take untoward risks, Mitya brushed this advice aside. "The minute we cast off, risk is all there is. What's solid and reliable is that," he said, pointing over Valery's shoulder toward San Francisco. "Out there," he said, gesturing over his shoulder, "it's as slippery as ice."

Aaron had approached to listen to this exchange. Mitya pulled him to his side.

"This is the last time I'll hug you until we're back, boy. From now on, I'm captain, and it's orders, not kisses, understand?"

Aaron nodded, pulled loose and shook Valery's hand. He did not seem afraid.

Valery watched them puff away from the docks and then raise their sails. It wasn't much of a boat to take on the largest ocean in the world.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.